Eliminating cervical cancer depends on global effort to ensure supply meets demand

Global access to HPV vaccine is vital, particularly in lower-income countries. Lessons learned from HPV roll-out could boost uptake of COVID-19 vaccines.

- 5 February 2021

- 4 min read

- by World Economic Forum

-

COVID-19 has overshadowed the global movement to vaccinate against cervical cancer.

-

Greater access to HPV vaccine is needed, particularly in lower-income countries where demand has outstripped supply.

-

Lessons can be learned from the challenges of implementing the HPV vaccine in order to boost confidence and uptake of COVID-19 vaccines.

The COVID-19 pandemic has taught us something about how to prevent a disease that kills hundreds of thousands of women every year: we need enough vaccines to go around.

Against the backdrop of the worst pandemic in 100 years, the recent launch of a new global movement to defeat another disease may have gone unnoticed. As COVID-19 continues to escalate, demand for vaccines outstrips their initially limited supply and threatens to prolong the pandemic. We now need to ensure vaccine supply doesn’t become the biggest obstacle to this ambitious new global effort of (for the first time in human history) eliminating a cancer.

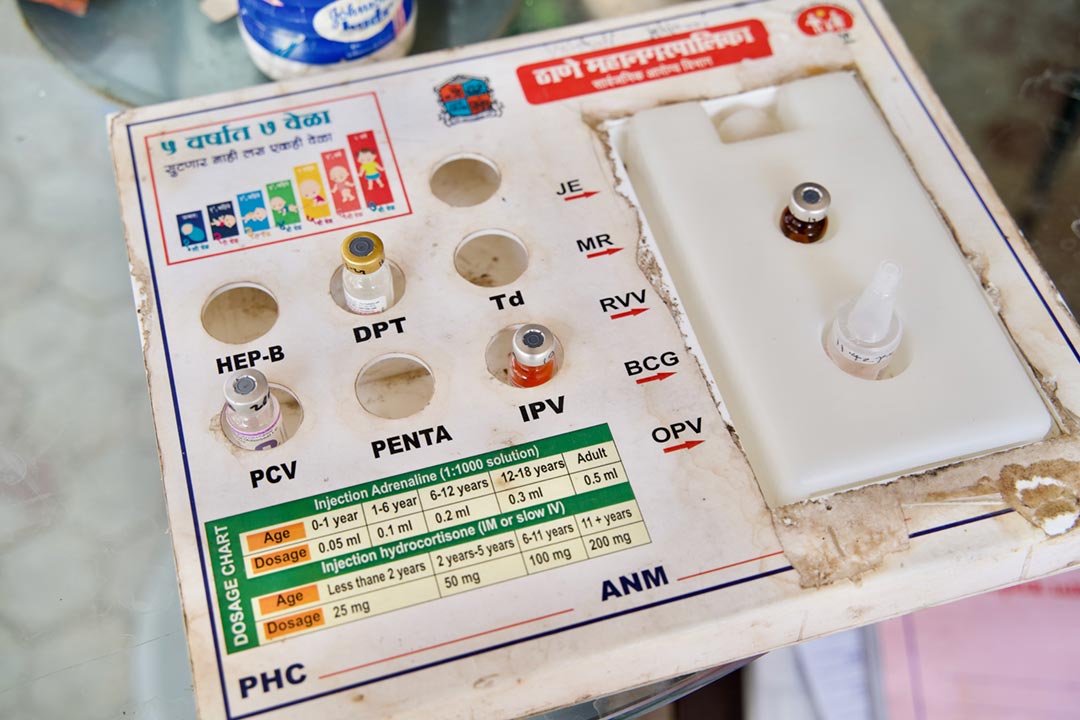

Cervical cancer is a deadly disease. Globally, it kills one woman every two minutes – more than 300,000 a year, and nearly all of them in low- and middle-income countries. These aren’t numbers: they are mothers, partners, daughters, sisters, friends. They are leaders, coworkers, neighbours, mentors. Every girl deserves protection against this terrible disease. But that’s not possible when there simply isn’t enough vaccine to go around.

As we have seen with COVID-19, once safe, effective vaccines are available, it’s essential that supply meets demand. But supply of vaccines against human papillomavirus (HPV), which protect against nearly all cases of cervical cancer, has been an ongoing challenge. This means that the global distribution of HPV vaccines is inequitable across geography, income and disease burden.

The relative lack of cervical cancer screening and treatment in many lower-income countries makes prevention through immunisation even more crucial than in higher-income countries. Thanks to work by my organisation, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, the HPV vaccine is affordable to lower-income countries – $4.50 per dose, compared with $100 in high-income countries. But price doesn’t matter if there’s not enough to buy.

Lower-income countries provide valuable insights

Since 2012, Gavi has supported the introduction of the HPV vaccine for girls in 21 lower-income countries, with 10 more in the pipeline. Yet the access gap is still far too wide: as of 2020, less than 25% of low-income and less than 30% of lower middle-income countries had introduced the vaccine, compared with 85% of high-income countries. As we’ve learned from the COVID-19 vaccine race, unless sufficient, timely supply of vaccines is distributed equitably, confidence dips, insecurity rises and people in poor countries may not have the same chance at a healthy future.

Have you read?

Despite lockdowns, a spike in vaccine hesitancy and misinformation, and a severe contraction in the global economy, lower-income countries have demonstrated extraordinary resilience in the face of unprecedented challenges since the pandemic began. In fact, there’s a lot that higher-income countries preparing to deploy COVID-19 vaccines can learn from lower-income countries about introducing a new vaccine in high demand – starting with how to prioritize high-risk individuals and groups.

For example, when lower-income countries were unable to vaccinate several ages at the same time because of paucity of HPV vaccine supply, they had to prioritize a single age. This is exactly what countries are doing now in deploying COVID-19 vaccines, in order to ensure that high-risk individuals, such as health care and other frontline workers, and vulnerable groups are the first to receive the protection they need. Once supply meets demand, that focus can be expanded.

Higher-income countries can also learn from the successes of lower-income countries in building confidence in, boosting demand for, and ensuring high coverage, of new vaccines – from community engagement, to TV dramas, to e-registers. Health professionals, civil society, religious leaders, social media and tech companies are key partners for governments and global health players in the roll-out of HPV vaccines.

Fight against cervical cancer

With the prize of eliminating cervical cancer in mind, in the long-term we may need to think about targeting further to ensure that the people most in need – those whose lives are most at risk – are given priority in the global context. Launched by the World Health Organization in November 2020, the “Global strategy to accelerate the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem” frames the fight against cervical cancer as a moral imperative: we must ensure that necessary health services continue despite the pandemic.

As 2021 begins, we can’t afford to lose one more life to a preventable, curable disease. And that means ensuring that a lack of supply of HPV vaccines to lower-income countries does not become the only barrier to this ambitious, but highly feasible, goal of eliminating cervical cancer – for good.

WEBSITE

This article is originally published by the World Economic Forum on 4 February 2021.

More from World Economic Forum

Recommended for you