In India’s tribal areas, climate change spurs rise in vector-borne infections

For villagers in Chhattisgarh’s isolated forest communities, malaria is both harder to prevent and more difficult to manage

- 11 April 2024

- 5 min read

- by Sweta Daga

In August 2023, Rampiyari Yadav, from Chhaparwavillage in the central Indian state of Chhattisgarh, spiked a fever. "I was so cold," she recalls. "My family kept putting blanket on top of blanket on me, but I was shivering. I started to wonder if I would die."

Three days into her illness, a Village Health Worker (VHW) from a local health non-profit called Jan Swasthya Sahyog (JSS) came to the house to test her for malaria. Yadav was positive.

"Extreme weather conditions have definitely increased and are worsening. We are getting more cases of sudden, heavy rainfall or drought, or more intense heatwaves."

– Dr Gayatri Kanchibhotla, scientist and State Weather Forecasting lead for Chhattisgarh

Her family took her to the JSS hospital, an almost 1.5-hour journey by road from their remote home. There, doctors diagnosed her with renal failure, a complication of the deadly parasitic disease.

Forest predator

India has made massive strides to contain its malaria burden in recent years. Today, a disproportionate number of the remaining cases are concentrated in "tribal" areas like this one. As much as a third of Chhattisgarh's residents belong to communities officially designated as scheduled tribes, and the state, home to just 2.29% of the population of India, sees a massive 18% of the country's malaria cases, according to 2019 figures.

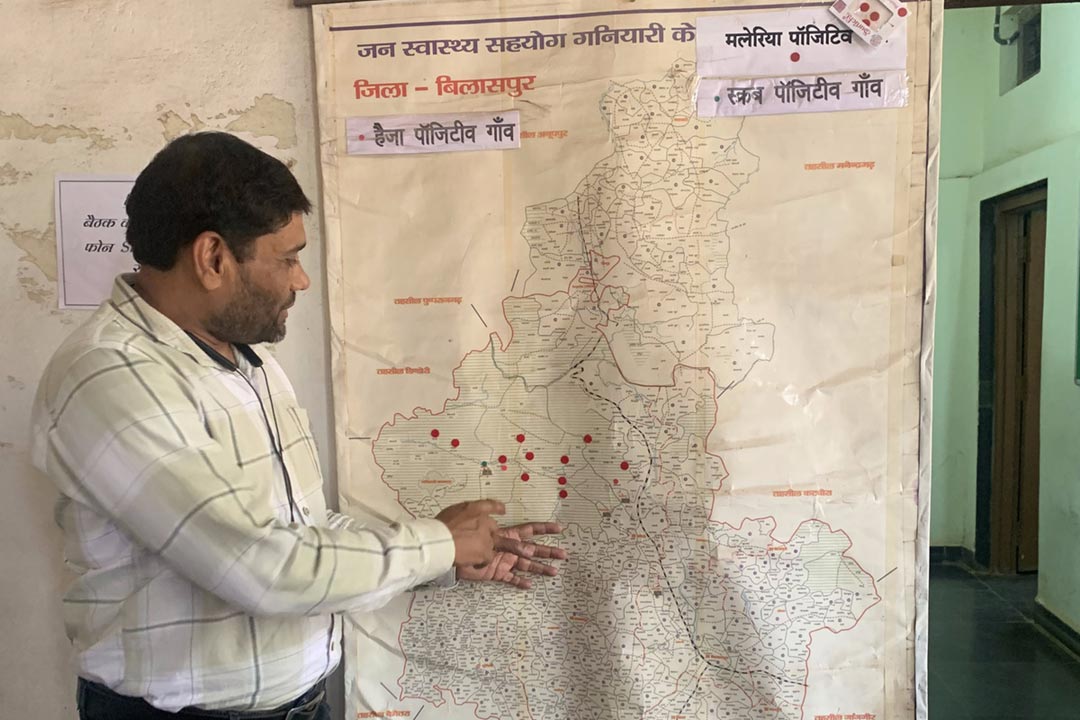

Praful Kumar Chandel has been the malaria programme coordinator at JSS for the last 22 years. "When we started in 2002, malaria was so prominent in this area that people used to call the state "malariagarh," not Chhattisgarh," he recalls.

The state is heavily forested, and a large part of its population lives within those forests, relying on them for at least part of their livelihoods. Often, forest-dwelling communities are relatively isolated from health care and other public services.

The years between 2002 and 2011 were very bad, Chandel says, with the JSS medical team treating a peak number of 717 cases in 2010.

The organisation experimented with models of prevention adapted to the communities they served – handing out specially-designed mosquito nets that communities could take with them to the forests, for instance, because many tribal people contracted malaria while out collecting firewood, feeding their animals, or gathering medicinal plants and edible tubers. The organisation also pioneered a unique blood sample courier transport system, making use of networks of school children and bus drivers to allow blood smear slides to be fast-tracked from VHWs to the JSS lab, enabling same-day diagnosis in an era before rapid, portable test kits.

Credit: Sweta Daga

"The numbers began to drop, and from 2020–2022, we barely saw two or three cases each year. But then, last year in August, we had 12 cases all at once, and they were all severe cases," Chandel says. Yadav, who eventually recovered, numbers among that dozen.

That raised an alarm for JSS. What was causing the spike? "People who are worried about health should worry about the changing climate," argues Dr Yogesh Jain, a paediatric doctor and co-founder of JSS.

Climate pressure

The World Health Organization's 2023 World Malaria Report underscores the connection between climate change and rising rates of malaria. "What the 2023 WHO report highlighted was Pakistan's 2022 floods and the impact that had on people's health. India should look at that example because we are neighbours. Our climates are similar in places," reflects JSS's Jain.

Have you read?

Dr Gayatri Kanchibhotla, scientist and State Weather Forecasting lead for Chhattisgarh in the India Meteorological Department, reports that in July 2023, just before JSS registered the bump in severe malaria cases, the state experienced notably heavy rainfall. "If we look at the larger pattern of weather over the past 30 years, there have been gradual changes in the amount of rainfall or day-to-day heat indicators, but what we can say is that extreme weather conditions have definitely increased and are worsening. We are getting more cases of sudden, heavy rainfall or drought, or more intense heatwaves. Last July 2023, we had very heavy rains, which could have led the rainwater to stagnate in some areas, and in forest areas, sometimes evaporation can be slow, giving time for mosquitoes to breed," she said.

Raghu Murtugudde, an earth systems scientist and professor at the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, explains, "malaria is a mosquito-borne disease, and mosquitoes rely on water for breeding, so it is related to rainfall. Water also gets collected in vegetation, and mosquito populations also depend on vegetation, which tends to be related to rainfall as well., unless there is a lot of irrigation."

"There are small things that can go a long way"

Soniya Bai and her two children, who live in a village not far from Chhaparwa, experienced fevers and headaches for about a month in August 2023. Their home is about fifteen minutes' walk from the nearest point accessible even by motorbike. In times of heavy rain, they can be completely cut off.

When she first felt the symptoms, Soniya Bai called the local jhola-chaap, or unlicensed medical practitioner, who gave her an injection of arteether, an antimalarial. It curbed her symptoms for a while and cost her 1,800 rupees (about US$ 21.60), but did not cure her.

After a month of feeling ill, Soniya, her husband and their two children finally walked to their closest JSS sub-centre, about 3 km away. "There is so much work at home," she says, "and there is only my husband and my mother-in-law at home to take care of it all. If I go to the hospital, who will do the work?" By the time she got to the JSS hospital, she was suffering from an enlarged spleen and severe anaemia, but was treated just in time. She and her children survived.

Dr Jain says that what is most important in confronting the mounting threat from vector-borne disease amid climate change, is to strengthen basic public health systems.

"There are small things that can go a long way," he says. "For example, people need to understand that bed-nets need to be changed or replaced every five years or so. We need to continue to research and diagnose people early, and our governments need to look at multiple factors. For example, to keep up immune systems, we need nourishing food. We need to be able to predict our changing climate more accurately.

"When we put these foundational steps in place, we have a greater chance at prevention and care. It's not just about the urgency at the time of an outbreak, but it's creating resilience at stages, including our systemic capacity to support local health care."

More from Sweta Daga

Recommended for you