Why southern and eastern Africa have the world’s highest rates of cervical cancer

Southern and East African countries have some of the highest rates1 of cervical cancer in the world. Prof Lynette Denny explains why, and what is being done to improve women’s health.

- 7 March 2023

- 6 min read

- by Linda Geddes

Seven of the top ten countries for cervical cancer incidence are in southern or eastern Africa. Why is that?

I think it’s due to a complex melange of reasons. There’s a very strong connection with poverty, with high numbers of people living in unsatisfactory conditions, as well as fragile healthcare systems that tend to focus on curative rather than preventative interventions, because there is such a high burden of disease. Access to healthcare is very limited for women over the age of 30, with virtually no successful screening programmes.

The highest incidence of HIV in the world is in eastern and southern Africa, and HIV is a big driver for co-infection with HPV and the development of cervical cancer.

For women who develop symptoms of cervical cancer, often there’s poor interpretation of their symptoms due to a lack of health literacy, or they rely on traditional health practitioners who tend not to examine women gynaecologically, which delays access to specialist care. Many women present with advanced disease, and only about a third of African countries have proper anti-cancer therapies, such as chemotherapy, radiation and surgical expertise.

Similar issues pertain in Southeast Asia and other low- and middle-income (LMIC) countries, where there is this combination of a high burden of disease, fragile and inadequate healthcare systems, lack of investment in preventative healthcare, and lack of health literacy amongst the population and health care workers – but it is particularly striking in eastern and southern Africa.

What about the role of other factors, such as HIV infection?

One area that has been less well-studied is the role of co-factors in HPV infection and its ability to cause cervical cancer. Some studies have found a link between vitamin A deficiency and high-risk HPV infection, suggesting it may promote more rapid oncogenesis – the process whereby normal cells are transformed into cancer cells.

Then there’s HIV. The highest incidence of HIV in the world is in eastern and southern Africa, and HIV is a big driver for co-infection with HPV and the development of cervical cancer. This relationship hasn’t been completely teased out, but most HPV infections will be cleared by the immune system, through what’s known as cell-mediated immunity, and this is the part of the immune system that gets damaged by HIV infection: HPV is able to flourish in that setting. It is also believed that because HIV infects and causes inflammation of the vagina and the lower genital tract, those inflammatory responses also enable and support HPV infection.

Prior to COVID-19, there were some very successful [HPV vaccine] implementation programmes, particularly in Rwanda, but also in Botswana, South Africa, and elsewhere. COVID-19 crashed everything.

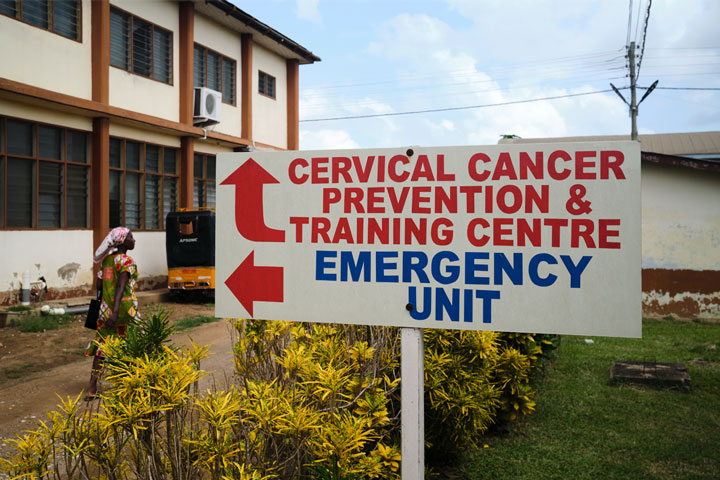

Is anything being done to improve cervical cancer screening in these countries?

The Pap smear was a highly successful health intervention, but the complexity of the infrastructure to maintain and sustain it was just too high in most LMICs. Since the mid-1990s, we have been looking for alternatives – and one of the most promising has always been DNA testing for HPV. In its original form, this was quite complex: it required a sophisticated laboratory set-up, and the result was delayed, like the Pap smear. It was also expensive.

But over the years, through a combination of good epidemiology and science, we have almost come to the stage of there being a good point-of-care test for HPV – where the analysis can be performed close to the patient, and a result generated almost immediately.

Since 2018, we have been investigating HPV DNA testing using a WHO-endorsed process called screen-and-treat. It involves a point-of-care test that analyses a sample from a woman’s cervix or vagina, and can tell whether they are infected with one of 14 cancer-associated HPV types within an hour. This means a woman can come to the clinic, get a test on site and, if it is positive, she can get treated on the same day, using a painless treatment called thermo-ablation, which burns away all the abnormal cells.

Have you read?

One of the biggest reasons for the failure of Pap smear-based screening programmes in LMICs is that the woman never gets the result – they may have to travel long distances to get to the clinic, health structures are fragile and inefficient, and it can take weeks to get a result, by which time the woman has forgotten she even had a test.

Our research group in South Africa has done a lot of work on this: we’ve shown that screen-and-treat is acceptable to women and it dramatically reduces this loss to follow-up, but there are challenges. The biggest is that most primary health care facilities – which in South Africa are probably the best you'll find on the African continent – are overloaded with patients, have no space and far too few staff. So it is going to take some innovation and ingenuity to integrate it into a primary healthcare setting and make it work.

What about HPV vaccines?

Prior to COVID-19, there were some very successful [HPV vaccine] implementation programmes, particularly in Rwanda, but also in Botswana, South Africa, and elsewhere. COVID-19 crashed everything, and many functional programmes became dysfunctional. At the same time, there was a shortage of HPV vaccines because in the Global North they were recommending vaccines be extended to older women and to boys, which meant there was less vaccine available in LMICs.

A recent study estimated that more than a million orphans are created each year due to the deaths of women from cancer – half of them being breast and cervical cancers.

Since COVID-19 has become less of an acute problem, many HPV programmes are waking up again. But there are still issues of availability associated with the current commercially available vaccines. Other vaccines are being developed though. For example, in India, the Serum Institute has developed its own HPV vaccine at a fraction of the cost, and we’re hoping that will become available very soon and will be much more dollar friendly for LMICs.

Why should counties invest in programmes like screen-and-treat or HPV vaccination?

Globally, more than 300,000 women die from cervical cancer, and about 80,000 women die in sub-Saharan Africa each year. These are women in their late 40s and 50s. They’re often the breadwinners, and the moral and emotional custodians of their families and communities. The death of these women has a dramatic downstream effect on individuals, and those families and communities.

A recent study estimated that more than a million orphans are created each year due to the deaths of women from cancer – half of them being breast and cervical cancers. If you look at what happens to those orphans, firstly, only 25% of those aged under ten will be alive in five years’ time. If they survive, they often don’t get proper schooling; emotionally and psychologically, they’re not supported as well; and these children have high levels of mental illness, substance abuse, HIV acquisition, and many other social problems.

If you can save the lives of these 300,000 women and enable them to be socially and economically active members of society, you gain so much economically.

Lynette Denny is a gynaecologic oncologist, and Professor of Special Projects at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Cape Town, and Director of the South African Medical Research Council Gynaecological Cancer Research Centre.

1. Source: https://www.wcrf.org/cancer-trends/cervical-cancer-statistics/