Côte d'Ivoire’s Vaccinated Gen-Z

On assignment for Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, Newsha Tavakolian traveled to Abidjan in Côte d'Ivoire to ask young entrepreneurs and creatives about their aspirations and what health means to them.

- 22 July 2025

- 7 min read

- by Magnum Photos

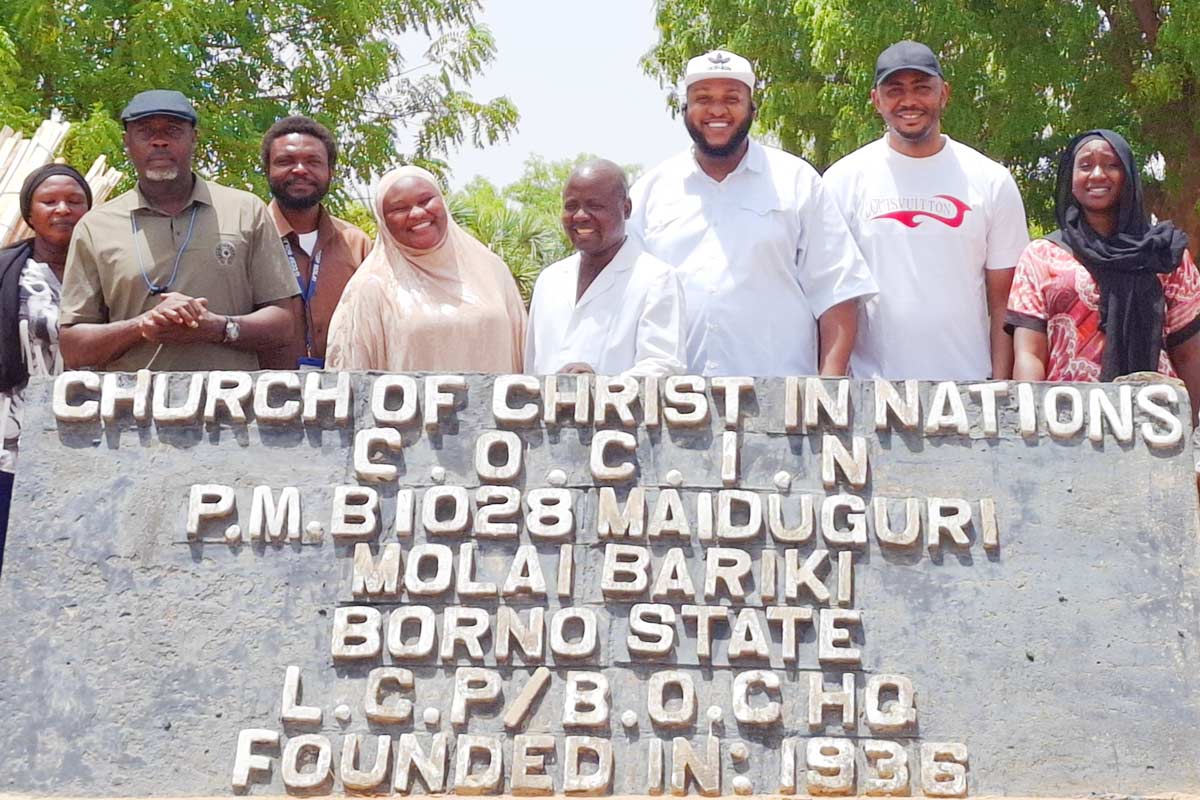

This story is included in a four-part series featuring Magnum photographers Nanna Heitmann, Salih Basheer, Jérôme Sessini and Newsha Tavakolian, who collaborated with Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, to document the impact Gavi-supported vaccines are having around the world. The project aligned with the 2025 Global Summit: Health and Prosperity through Immunization on June 25 in Brussels, where the photographers presented an exhibition of their work.

Through the Gavi-backed multi-year immunization plan, in partnership with the World Health Organization (WHO) and UNICEF, the percentage of children vaccinated with DTP3 — which protects against diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus — went from just over 50% in 1999 to 79% in 2023.

In June 2025, on assignment for Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, Newsha Tavakolian traveled to Abidjan, the largest city and economic capital of Côte d'Ivoire. She photographed the next generation of artists, designers, entrepreneurs, and architects driving the country’s economic and social progress. Twenty-five years ago, they were among the cohort of children vaccinated through Gavi’s immunization program, which introduced new, life-saving vaccines.

Through the Gavi-backed multi-year immunization plan, in partnership with the World Health Organization (WHO) and UNICEF, the percentage of children vaccinated with DTP3 — which protects against diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus — went from just over 50% in 1999 to 79% in 2023, according to Gavi’s records. Now in their twenties, Abidjan’s Gen-Z is contributing to their country’s growing economy, improving civil liberties and dynamizing the country’s social fabric.

For Jean-Luc, health is primal. “I’m a photographer, I’m an architect. If I’m not well, I can’t go anywhere to take photos, I can’t see what I’m photographing, I can’t listen to music that inspires me,” said the twenty-four-year-old artist, originally from Burkina Faso. Tavakolian spoke to him on one of Abidjan’s beaches at the edge of the coastal city, while children played in the surf, despite the overcast weather.

Among the 18-35 year olds who make up approximately 36% of the population, Jean-Luc is fascinated by African cultural theory and self-development. He aspires to create art “that is not only aesthetic, but also educates the African youth,” he told Tavakolian. He believes that art can shift political attitudes, and worries about the lack of empathy that fuels war. Certain events during the First Ivorian Civil War from 2002-2007 have left their mark on him.

In many ways, Côte d'Ivoire is also still recovering from the Second Civil War in 2011, during which 3,000 people were killed and approximately 500,000 displaced. After the 2020 presidential elections, more violence ensued, with more than 50 people killed. In more recent years, the country has battled through repressive laws against freedom of expression and restrictions on NGOs, Amnesty International reports. Yet, with the help of its dynamic youth, the country’s overall economic, political and social stability has endured, according to the International Monetary Fund. With Gavi’s support, the government plans to expand its universal health care coverage.

Tavakolian also met 26-year-old flower shop owner, Tarah, in one of her four vibrant flower boutiques in Abidjan. From managing and communications to operations, Tarah is busy running her business, which has garnered a strong social media following. Actively against “all kinds of discrimination”, she too is conscious of the impacts the war had on the collective memory. “I was still a bit young, but I was aware of what happened,” she said. “The fact that so many people died, it’s something I would never want to happen again.”

For Tarah, “health is being able to wake up, move, breathe, eat, and feel good. It also includes your routine. Once you have health, you can do anything,” she added. She remembers being vaccinated as a child, thanks to the introduction of routine vaccination campaigns. After her business studies, she returned to Côte d'Ivoire, and despite financial uncertainties during the Covid-19 pandemic, she decided to open her first flower shop, fulfilling her “passion for entrepreneurship and the development of my country.” “I studied abroad, but I knew I would end up living here, because this is my home,” she said.

Proud of her queer identity and independent spirit, 25-year-old fashion designer Alida started her own brand after her studies. She now has several stores and online platforms to showcase her creations, which fuse tribal graphics with a modern twist.

Have you read?

According to a French National Council for Human Rights (CNDH) study, Abidjan has been a hub for the queer community, and the Côte d'Ivoire itself is known to be more LGBTQ+-friendly compared to its West African neighbors. But in October last year, social media influencers incited a series of violent assaults and beatings on gay and trans men in Abidjan, with more than 45 assaults reported by early November 2024. Soccer fans at the Africa Cup of Nations qualifiers also brandished banners with homophobic slogans last September.

Despite this aggression, Alida is committed to embracing her queer identity, and hopes that the society and institutions in the Côte d'Ivoire, where same-sex partnerships and marriage are not recognized, will become more accepting of the LGBTQ+ community. “Being healthy means being OK in my mind,” she said, attributing nature to improving her mental health. “If I’m not physically and mentally healthy, I can’t do anything, so it’s very important to me,” she adds. She hopes to help younger LGBTQ+ people to “be themselves” — “peace is inside”, Alida concludes.

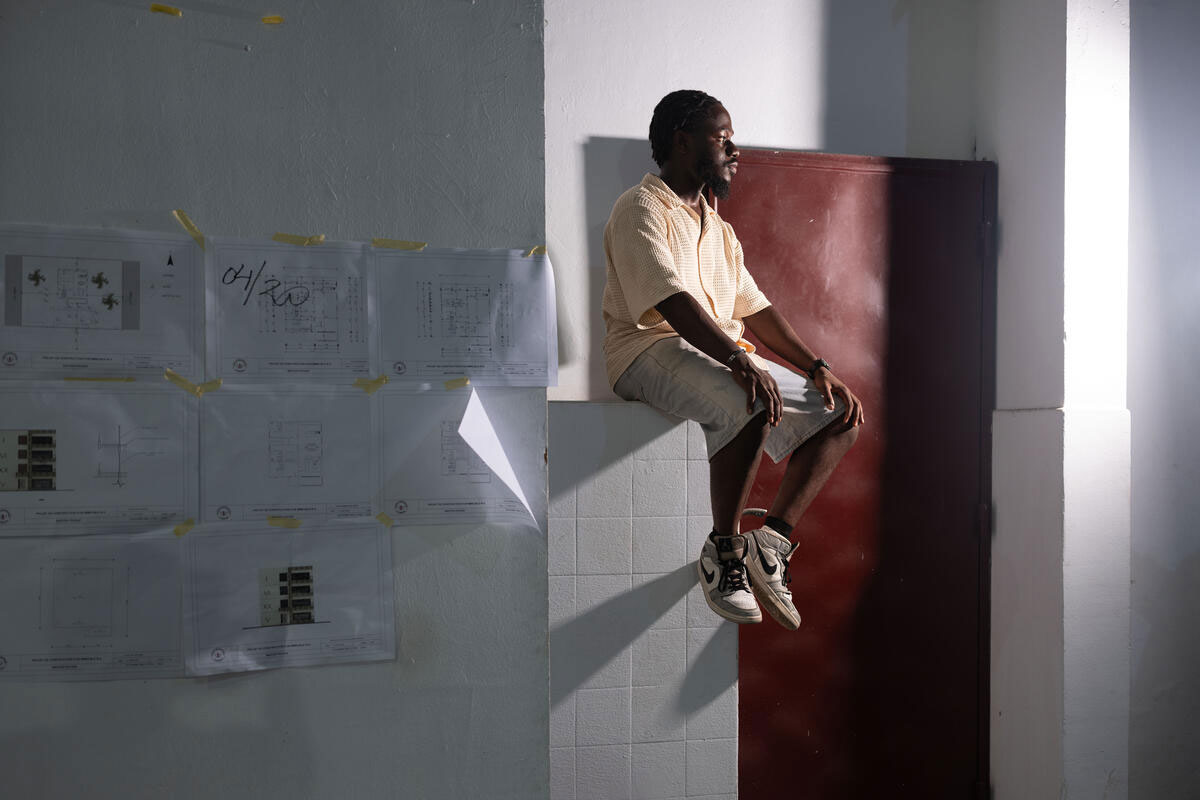

In Abidjan’s School of Architecture, young architects are busy marking blueprints spread out on the tables of an open workspace. Yem, an architect himself, wanted to have his portrait taken there, where he studied. If vaccines helped to save his life in his youth, the school helped save his life in young adulthood, he claims. He’s interested in how he can incorporate ancestral skills and knowledge into his work. “It’s true that we’re used to saying that, in Abidjan, you absolutely have to be well connected, but I’m more of the mindset of working hard to better myself — of improving myself everyday,” he said.

Historical context is foundational to Yem’s current political outlook: “There are many complexities about black history and black values, and the first step is to have confidence in ourselves, then we’ll be more apt to know our rights, to reclaim them, and recognize them.” He’s optimistic about the country’s future, although he’d like to see the government dynamize more social change, and for the younger generation to prioritize action and authentic transformation over online passivity. In terms of his health, Yem uses sports to stay active — “when I’m not doing sports, I don’t feel well,” he says.

Myriama, a 25-year-old communications manager, acknowledges that health is not only physical but mental. She went through a two-year period of having depressive thoughts without knowing what was wrong, and her weight dropped significantly — “I would cry about everything”, she said. After her feelings worsened, she spoke to her father, who encouraged her to consult a therapist, which brought about a positive shift. She realized how mental stability is paramount to one’s overall health. “I’ve learned to count solely on myself, to expect things only from myself,” she said.

Between enjoying Abidjan’s beaches and gardens, Myriama is now looking for a job to support herself. Earning enough money to live comfortably in the future is one of her current preoccupations. “People usually don’t get paid enough, and life and rent is expensive,” she said. “I’m 25 years old, and I want to live in my own home. But if I’m paid the average salary, how will I ever save up for a house?” She notes that Abidjan’s rapid urbanization creates evident economic disparities between neighborhoods. Last year, thousands of the city’s residents were evicted and left homeless without adequate consultation or notice, under the pretext that the areas were flood risks, while the mass demolitions were in fact to build roads.

Tavokalian’s visual investigation illustrates how large-scale immunization programs can impact a generation 25 years down the line. “Over the years, Gavi has invested more than $528 million in Côte d'Ivoire in the form of vaccine purchases, financial support, cold chain equipment, and technical assistance,” Gavi’s website states, helping to prevent more than 230,000 deaths. Gavi will continue to finance the Ivorian government’s routine immunization program until 2030.