In Kenya’s Kibra, nurses carry the HPV vaccine gospel

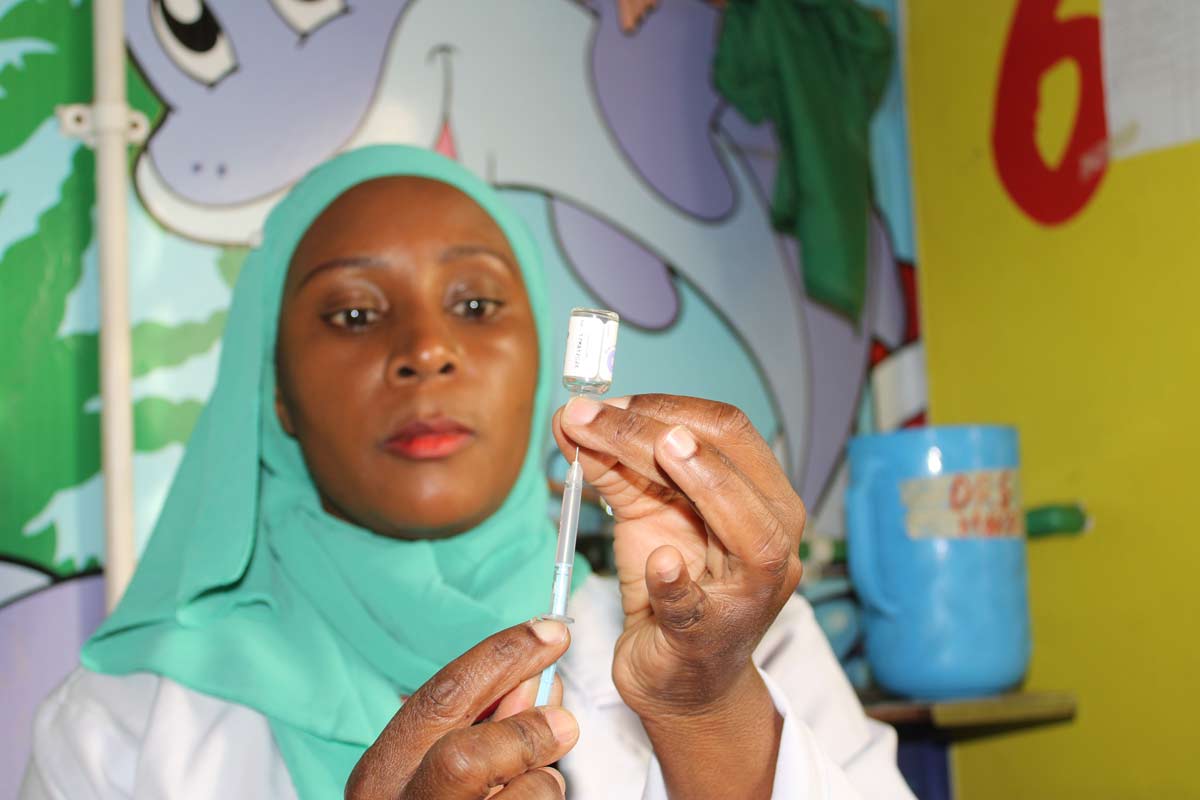

In the informal settlement often described as Africa’s largest slum, social realities make it trickier to mainstream the cancer-blocking jab. Nurse Lencer Akinyi and her colleagues are not backing down.

- 25 March 2025

- 7 min read

- by Muthoki Kithanze

Speaking softly, but with urgency, nurse Lencer Akinyi explains the importance of observing hygiene – particularly of boiling drinking water – now that heavy rains are expected.

Her words are punctuated with the refrain, “Mumenielewa?” – Swahili for, “Have you understood me?” The small gathering of people assembled in the waiting bay of Karanja Road community clinic in Nairobi’s Kibra informal settlement murmur their assent. Afterwards, one or two patients approach Akinyi individually, perhaps in search of more information on the topic, or hoping to consult her on a private matter.

This is a regular Monday ‘health talk’, for which the nurse allocates just 15 minutes before she returns to the triage room and seeing patients.

That sounds brief, but it can be immensely impactful. Josephat Muyayi, a resident of Kibra and a father of four daughters, attended a similar talk last year, and heard Akinyi describe the importance of giving eligible girls the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, which is capable of blocking more than 90% of cervical cancers. Cervical cancer kills a reported 3,591 Kenyan women a year, making it the country’s single deadliest cancer.

Joining Akinyi’s health talk finally thawed his doubts, Muyayi said, and he permitted his third-born daughter to receive the jab.

“It is not like I did not know of the vaccine; I had heard about it from multiple sources even during parent meetings at school when Lencer’s team spoke to us,” he tells VaccinesWork. But when he retreated to his community, swirling rumours and misinformation initially overshadowed the medical advice.

Akinyi says repeated sensitisation efforts are important, especially in Kibra, known as the biggest informal settlement in Africa, which is characterised by poor living conditions and high poverty levels.

Reaching Kibra

“The population in the slum is unique. Some people may not have smartphones and televisions where they can get regular updates on health matters, others have not had a formal education; these factors combined can generate vaccine hesitancy,” explains the nurse.

Many myths circulate in the clinic’s catchment area, and the community has competing interests, like searching for basic needs such as food, which can relegate vaccination down the priority list of even the most dedicated parents. Muyayi, for instance, speaks with deep affection for his daughters, reflecting on the challenges of raising them in a setting where drug abuse and early sex pose twin challenges to young people’s health.

There are also challenges specific to the HPV vaccine. The jab is recommended for girls between the ages of 10 and 14 in Kenya, and is often administered on school campuses – but in informal settlements like Kibra, higher rates of school absenteeism and early dropouts can mean fewer girls get access at the classroom. Moreover, mobility within informal settlements can mean girls lose contact with vaccinators, and early sex and marriage can raise the exposure risk to the cancer-causing virus, which can spread via sex and other forms of contact.

Although there is no national data to illustrate a disparity in HPV vaccination rates between informal settlements and communities of higher socio-economic advantage in Kenya, healthcare workers and experts who spoke to VaccinesWork anecdotally confirmed a gap.

To help bridge it, Akinyi and other health providers, including community health promoters (CHPs) and public health officers attached to the small facility in Kibra, have rallied together to ensure every eligible girl in their area receives the vaccine.

Rising immunisation rates

Their efforts are bearing fruit. “In 2022 our vaccination for HPV-1 was 1,946 and 1,659 for HPV-2. In 2023 the numbers rose to 2,806 and 1,790 for HPV-1 and HPV-2 respectively,” says Anne Boraya, sub-county public health nurse, Kibra.

Akinyi reflects with a laugh of relief that things have changed since the early days, when school children would turn up on campus on vaccination days with consent forms marked “do not vaccinate” in red ink.

“After observing this, we decided to request school heads to allocate sufficient time for health talks during school meetings, allowing parents to ask questions,” she says.

The health workers initially relied on giving health talks to children on the understanding that the children would pass the message to their parent – that, plainly, wasn’t cutting it.

Organising school vaccinations is no small feat, explains Akinyi, who reports being met with reluctance from some school heads, often needing to make several approaches before she gets the nod.

That’s a major time-commitment, especially given that her health facility is also not served by a vehicle, meaning she and her colleagues workers must cover any distance they travel on foot.

But both Akinyi and Boraya report that repeated interaction with schools has fostered trust in the school heads, to the point they now receive unprompted requests from private school administrators who had previously resisted, to set up vaccination days.

Changing minds

When girls are unreachable in school, health workers trace them to their doorsteps. Rukia Jamaldin, a CHP in Kibra, has been mapping eligible girls since 2019.

“There are places I go to and get chased away because some members of the community believe that you are being intrusive when you approach them, so they tend to avoid engaging with you, but I never give up,” she says, her eyes widening with joy.

When she’s met with resistance, Jamaldin has learned to enlist the help of colleagues who she trusts can get a better reception.

She shares modestly that she often finds herself using her own money to buy medications for sick community members and paying their transport fare to the hospital.

“If you do not assist someone in need, they are unlikely to listen to you or adhere to vaccination recommendations,” she says, adding thoughtfully that it is easy to think of being a CHP as a passion rather than an income-generating activity. When she is not doing community rounds, Jamaldin runs a small business outside her house to augment the small stipend she receives as a CHP.

The mother of four also tracks emerging NGOs that support girls, and persuades them, often successfully, to allow her to speak on the topic of sexual reproductive health. It’s a topic that needs careful handling, she knows, because inaccuracy can generate misinformation.

The team from the Karanja Road facility has partnered with at least three NGOs to support their vaccination efforts so far. Jamaldin also tries to engage with households in religious sects that do not support vaccination.

“I make numerous trips until I wear them down, and some will say, ‘alright, give her, but do not mention it to other people’,” she says with a reassuring smile.

Have you read?

Millions protected

Since the roll-out of the vaccine in 2019, 3.3 million girls have received the HPV-1 vaccine and 2.3 million have received HPV-2, Dr Wesley Mugambi, an official from the Kenyan Ministry of Health revealed last month during a media forum.

“Last year more girls received the second dose, with 602,741 vaccinated for HPV-2 and 519,391 for HPV-1 and we hope to keep the numbers rising this year,” he added.

He also mentioned the HPV vaccination policy will this year revert to a single age cohort of girls aged ten years as routine.

But for the HPV vaccine to attain the systematic acceptance that older vaccines like the measles jab or polio drops have in Kenya, the message needs to “become part of the community,” Peter Njoroge, Nairobi County Deputy EPI Logistician says.

“If you walk around Kibra, you’ll still see messaging about COVID-19 vaccines," he notes, referring to murals done by members of the community, and printed T-shirts that continue to promote uptake of that pandemic-quelling jab.

Meanwhile, bringing the vaccine into the community is exactly what Akinyi is doing, day to day. Waida Kasaya, clinical officer and team leader at Karanja Road says, “Our only goal is to work with everyone to stop women from dying from a preventable illness.”

More from Muthoki Kithanze

Recommended for you