Beyond the shot: what COVID-19 taught Pakistan about vaccine hesitancy

Trust is as indispensable as syringes – and quite possibly more complicated to manufacture.

- 23 July 2025

- 5 min read

- by D. Aminah Khan , Dr Fahad Abbasi , Areej Javed

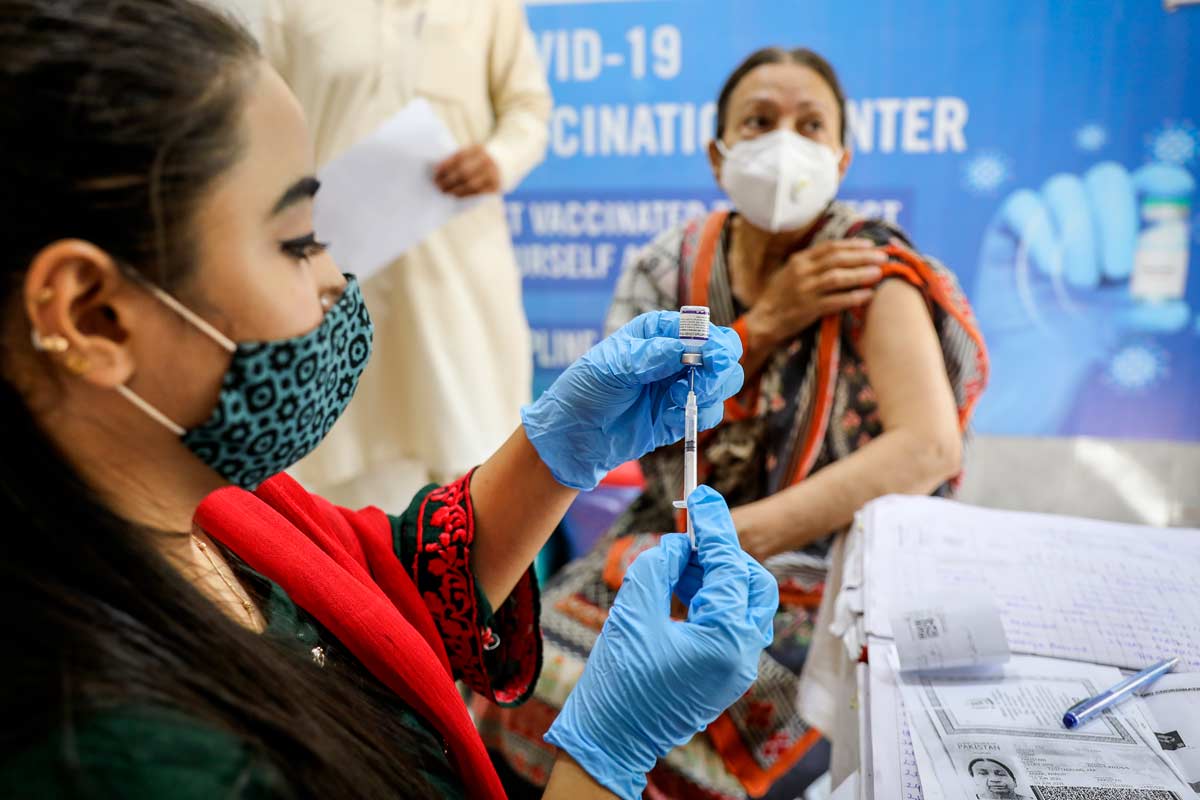

“It was not the virus we feared, it was the rumours,” a senior district official recalls saying at a District Health Office Coordination Meeting held back in 2021. A Lady Health Worker (LHW) from Peshawar, meanwhile, looks back on the COVID-19 immunisation campaign and says, “People believed we were there to inject poison. I stopped asking about the vaccine. I started asking how their day had been.”

In Pakistan, as in many countries, the COVID-19 pandemic had stirred up doubts and anxieties. Myths, seeding mistrust of the vaccine, swirled.

But the quiet pivot the anonymous Lady Health Worker alluded to – away from instruction and towards conversation – might have been one of the most powerful lessons COVID-19 taught us. Because when it comes to vaccines, trust is not a bonus. It’s the baseline.

In fact, multiple voices from the qualitative exploration of COVID-19 Delivery Support Phase III (CDS III) project, implemented by Jhpiego in partnership with the Federal Directorate of Immunization (FDI) and supported by Gavi, expressed their belief that in the earliest days of roll-out, the biggest challenge for the country wasn’t just logistics: it was trust amongst the communities, caregivers and health workers themselves.

Trust is the keystone

As part of Jhpiego Pakistan’s technical assistance for the country’s COVID-19 pandemic response, we set out to reflect on the best practices and learnings gained from CDS III on this observation. The goal was to capture what worked – and what didn’t – during the pandemic response, and to understand how these learnings could strengthen not only Pakistan’s pandemic preparedness, but also its routine immunisation system.

What followed was six months of deep, qualitative exploration, based on key informant interviews and focus group discussions, and carried out across Pakistan’s provinces and federal-level administration. We heard from decision-makers at policy level, mid-level manager, and community health workforce including vaccinators and lady health workers who were actively engaged during the pandemic. Our questions: What factors determined whether people trusted or rejected the COVID-19 vaccine? What helped health systems reach the unreached? What lessons could outlast the emergency?

The answer that echoed across the country was clear: you can have doses, dashboards and delivery systems but unless the community trusts you, none of it works.

You can’t force it

Despite a massive effort, vaccine hesitancy remained a persistent barrier. Misconceptions that the vaccine could lead to infertility, death, or be tied into shadowy foreign agendas circulated rapidly through social media and community gossip. As one Lady Health Worker in Peshawar put it:

“People would ask us – what’s in this vaccine? Why are foreigners so eager to inject us? We had no answers at first.”

One district health officer in Balochistan told us, “In some communities, it wasn’t that people refused the vaccine. They just didn’t believe we had their best interest in mind.”

At both national and provincial levels, the use of coercive policies in Pakistan’s COVID-19 vaccination campaign significantly undermined public trust. Vaccines were tied as conditions to access to essential aspects of daily life such as employment, travel and even mobile phone services, creating a climate of anxiety and deepening vaccine hesitancy among communities, caregivers and even health workers. On paper, it had worked: by 2023, more than 85% of Pakistanis had received a first dose, and over 65% had completed their second and booster doses. But this came with unintended consequences.

In the months that followed, the country saw a decline in demand for routine immunisations, especially in communities where coercion was used during the COVID-19 response.

“People came to get vaccinated because they had no choice,” one EPI (Expanded Programme on Immunization) officer in Lahore told us. “But they left feeling resentful, not reassured.”

One respondent noted: “The vaccine mandates helped with coverage, but people complied out of fear, not conviction. That distrust could linger.”

It became clear that compulsion could not replace communication. The real shift came when the approach pivoted to community-led engagement.

A talking (and listening) cure

Fortunately, Pakistan’s health system didn’t rely solely on top-down strategies. Over time, the emphasis shifted to community-based approaches, and with it, vaccine confidence began to grow.

In rural Sindh, one health team brought in a respected religious scholar to host a live Q&A with mothers at a local clinic. “He told them the vaccine was halal (an Arabic term meaning ‘permissible’ or ‘lawful’),” a vaccinator recalled. “But more importantly, he answered their fears patiently.”

In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, tribal elders were enlisted to demonstrate vaccinations publicly. In urban Karachi, digital campaigns were supplemented with in-person visits from female health workers, who knew the nuances of their neighbourhoods better than any call centre or SMS.

What made these interventions effective wasn’t just their format – it was their familiarity with communities, culture and language. People listened to those they knew, not those they saw on a billboard.

One provincial EPI manager reflected: “We didn’t bring in outsiders. We relied on local doctors, vaccinators and health workers. They were already trusted, and that made all the difference.”

Throughout the response, it was Pakistan’s frontline health workers – especially the LHWs – turning top-down directives into bottom-up change. They navigated poorly ventilated homes, aggressive rumours, long hours and, sometimes, outright hostility. But day after day, they showed up. In many communities, their consistency was what turned suspicion into acceptance.

“We were scared too,” said one vaccinator. “But when we kept coming with authentic information, people noticed. That’s when they started trusting us.”

Have you read?

The CDS III project also revealed hard truths: routine immunisation (RI) suffered during COVID-19. Redirected resources, including RI vaccinators deployed at COVID-19 vaccination centres, and shifting priorities meant zero-dose children were often missed. Therefore, Jhpiego’s CDS-III report calls for integrating emergency systems with routine platforms, because both need each other to survive.

Pakistan’s experience illuminated a difficult truth. Public health isn’t just about getting vaccines into arms; it’s about belief and belonging. Because when you ask someone to take a vaccine, you’re not just offering protection, you’re asking for trust. And trust isn’t built in press conferences or apps, it’s built in whispered reassurances between a health worker and a worried caregiver. It’s built when people feel seen, heard and respected.

As the world braces for future outbreaks, Pakistan’s story offers a simple, powerful reminder: misinformation thrives in silence. Trust grows in dialogue.

If we want robust, equitable health systems, we must invest in both vaccines and the relationships that carry them.

Authors

Dr Aminah Khan – Country Director, Jhpiego Pakistan

Dr Fahad Abbasi – Technical Advisor, Gender and Research (Project Lead CDS-III)

Areej Javed – Communications and Knowledge Management Coordinator, Jhpiego Pakistan

More from D. Aminah Khan

Recommended for you