Cameroon’s Big Catch-up is a mountain to climb

Cameroon’s march toward reaching every child with life-saving vaccines has faced a cocktail of challenges, despite high levels of support from the population.

- 5 December 2024

- 7 min read

- by Nalova Akua

Taking a day off from farm work for any reason is something Aïssatou Nabila, from the village of Mbarang in the Meiganga district of Cameroon’s Adamawa region, tries to avoid at any time – and it’s certainly not something she’s eager to do during the ongoing peak farming season.

But the 29-year-old mother-of-two quickly was willing to take a pause when an unexpected opportunity to have her children vaccinated against poliomyelitis showed up on a Saturday, in late November.

"Between 130,000 and 150,000 zero-dose children have been recorded in Cameroon every single year since 2019."

- Dr Tchokfe Shalom Ndoula, Permanent Secretary of the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) in Cameroon

“I feel so happy having Trésor [two years old] and Fadimatou [six months old] vaccinated against polio; they felt very okay after taking the vaccine,” Aïssatou told VaccinesWork on phone. “They are now up to date with their vaccination schedule.”

The polio vaccination campaign was organised in the Adamawa, East, Far North, and North regions of Cameroon – alongside neighbouring Chad, the Central African Republic, Nigeria and Niger – from 22–25 November 2024, in response to the type 2 polio variant epidemic recently confirmed in the sub-region. An estimated 3.5 million Cameroonian children aged 0 to 59 months, among them those who missed one or more routine vaccination appointments, received two drops of the oral polio vaccine.

This transnational polio vaccination campaign was a logical follow-up to a prior drive, which took place from 24–27 October, targeting at least 6 million Cameroonian children.

Credit: EPI Cameroon

Catching up children, tamping down outbreak risk

A common thread in the two campaigns was their association with the Big Catch-up, an important policy initiative that is being replicated across many countries to close immunisation gaps caused by the immunisation coverage backsliding during the COVID-19 pandemic. The aim is to restore global immunisation levels – still at 80% in 2023, after falling from 86% to 81% over the course of the first year of the pandemic – and strengthen immunisation systems.

The first phase of this drive took place in Cameroon from 23–29 September, targeting 80 of the country’s 204 health districts – those believed to be home to the highest number of zero-dose and under-immunised children. The next phase is slated for mid-December.

"The goal of the Big Catch-up is not to vaccinate all these children [at once] as this is impossible, but to vaccinate a good number of them in order to achieve herd immunity."

- Dr Tchokfe Shalom Ndoula

During the drive, children below five are administered one or more of the 15 vaccines found in Cameroon’s routine immunisation programme, which include vaccines against killer diseases like tuberculosis, poliomyelitis, tetanus, viral hepatitis B, measles, rubella, yellow fever, rotavirus diarrhoea, and, recently, malaria.

Not quite coincidentally, the Big Catch-up is taking place at a time the central African nation is grappling with a resurgence of some vaccine-preventable illnesses. Cases of measles were only recently confirmed in the Centre, North, Far North, Littoral and West regions of the country – as was yellow fever in other regions.

Locating the missing

For Dr Tchokfe Shalom Ndoula, Permanent Secretary of the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) in Cameroon, the Big Catch-up is not just another vaccination campaign, it is a strategy to find and vaccinate those children who have missed out on life-saving vaccines in the extraordinary years since 2019.

Credit: Nalova Akua

Between 130,000 and 150,000 zero-dose children have been recorded in Cameroon every single year since 2019, he says.

The consequence: the country currently harbours more than 600,000 zero-dose children and more than 700,000 under-immunised children.

“The goal of the Big Catch-up is not to vaccinate all these children [at once] as this is impossible, but to vaccinate a good number of them in order to achieve herd immunity,” Dr Ndoula tells VaccinesWork. “That is why we have set an attainable objective: to vaccinate at least 70% of children aged between 12 and 23 months (i.e. who missed out on their vaccination since last year); and also vaccinate 30% of children aged between 23 months and 59 months. This gives us a total of about 271,000 children to catch up with by 2025,” he said.

"Again, [parents] were more happy since this activity was carried out right in their homes without having them move away from homes to vaccination posts. Notwithstanding, we faced problems of insecurity, poor internet connectivity, poor electricity supply and poor road network."

- Dr Cornelius Chebo

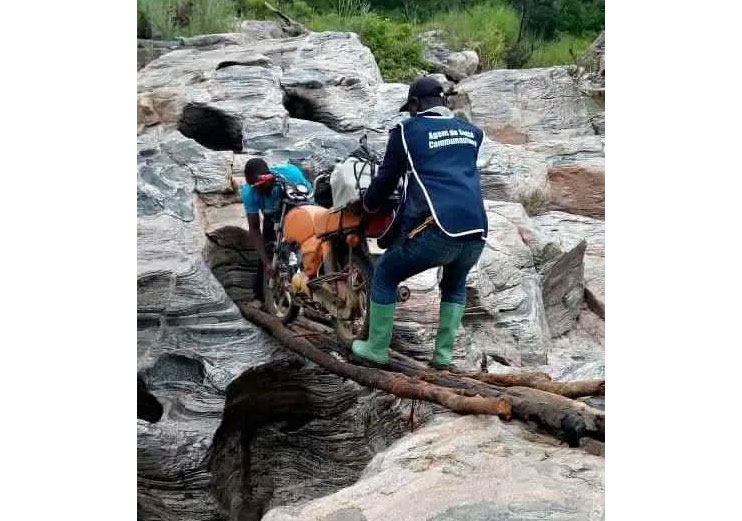

To attain this goal, the country has rolled out a national strategy of tracking, catching and vaccinating zero-dose children wherever they may be found. “Our findings reveal that zero-dose children are concentrated in three different zones in Cameroon,” reveals Dr Ndoula. “The first zone includes those communities which are situated very far off from health services with irregular or inexistent vaccination services. Health workers either need a canoe to get to these communities or are bound to walk many kilometres,” he said.

Credit: EPI Cameroon

The second zone that harbours zero-dose children are disadvantaged urban areas dotted across the capital city Yaounde and other highly populated cities such as Douala and Bafoussam. These zones have limited or no access to basic health services, according to Dr Ndoula. Growing insecurity in the country’s far-north (caused by Boko Haram insurgency), north-west and south-west (civil unrest) also breeds zero-dose children.

Have you read?

“Having known the different zones harbouring zero-dose children and reasons behind their inability to get vaccines, we have developed different strategies: enlist social mobilisers and community health workers to beef up the existing health staff in a given health district and equipping them with necessary resources to get to hard-to-reach areas to vaccinate these children,” Dr Ndoula explains.

“For the disadvantaged urban areas, we bankroll associations to get to the neighbourhoods, dialogue with parents and vaccinate their children. While in insecure areas, we depend on humanitarian organisations. In addition, we have tools that help us monitor our progress toward the attainment of set goals by knowing at every given moment the number of zero-dose children left.”

Adamawa parents show support

This strategy has been replicated in different parts of the country with assorted outcomes. Mohamad Anouar al Sadat, head of the Meiganga health district in the Adamawa region estimates that some 98% of parents showed “adherence” – meaning they stepped up and were supportive of the drive’s aims – during the first phase of the Big Catch-up.

Credit: EPI Cameroon

“Social mobilisers went from door to door to identify zero-dose children especially in hard-to-reach areas. A preliminary list was drawn up by the heads of health facilities and given to vaccinators to find under-immunised children,” Anouar told VaccinesWork. “Challenges included on-site management of teams and mobility-related problems such as limited or no means of transportation.”

Littoral inequities

Down in Cameroon’s Littoral region – where vaccination coverage rates stand below 80% – barely 3,000 of the targeted 16,000 children from the four selected districts (Edea, Manoka, Dibombari and Mbanga) were vaccinated during the first phase of the Big Catch-up, giving a coverage rate of 18.75%. The health districts were selected because they have unimmunised children and hard-to-reach zones, but most importantly, for reasons of health care inequity, says field epidemiologist and EPI coordinator for the Littoral region, Leonard Ewane. He pins the dismal vaccination outcome on inaccessibility, vaccine hesitancy and paucity of information.

“We had difficulty tracking these children given that the Big Catch-up is not just any normal door-to-door vaccination campaign,” Mr Ewane tells VaccinesWork on phone. “We didn’t know where precisely to find these zero-dose children. Usually, they are either children who are new in a given area; those whose parents are hesitant to have them vaccinated or simply children with no vaccination record. At the end of the day, the target we set may or may not tie with the local realities,” he said.

Reaching the crisis-hit regions

In the crisis-affected north-west, just 914 zero-dose children (out of identified 17,203) as well as 837 under-immunised children (out of identified 17,203) were vaccinated during the first phase of the Big Catch-up. Only six of the region’s 21 districts were involved.

Nonetheless, Dr Cornelius Chebo, coordinator of the EPI and the Centre for Epidemics and Pandemics in the region says parents were happy to receive social mobilisation teams. “Some areas which had never been covered due to the crisis could be covered thanks to the Big Catch-up,” Dr Chebo tells VaccinesWork.

Credit: EPI Cameroon

“Again, [parents] were more happy since this activity was carried out right in their homes without having them move away from homes to vaccination posts. Notwithstanding, we faced problems of insecurity, poor internet connectivity, poor electricity supply and poor road network,” he said.

In the war-torn south-west, the use of firewalling, door-to-door campaigns and school strategies led to the effective management of 97% refusal cases.

“The use of technical staff as social mobilisers gave a plus in the activity as [locals] have confidence in their nurses whom they meet in health facilities for other health interventions,” confirms Martha Ndiko Ngoe, unit head in charge of surveillance, monitoring and evaluation at the EPI Regional Technical Group in Cameroon’s South West region.

“Districts also used the ‘evening strategy’ where the parents and caregivers are at home and can help the team to identify eligible targets and give their consent for vaccination especially where vaccination in the school milieu is challenging,” she told VaccinesWork.