Cameroon hits back at yellow fever

Recent years have brought a yellow fever resurgence to Cameroon. Last month, a targeted vaccination campaign pummeled the chain of transmission in seven especially vulnerable health districts. Nalova Akua reports.

- 15 May 2024

- 8 min read

- by Nalova Akua

Neither Patrick Koulagna nor Moise Hamadjida, both residents of Meiganga district in the Adamaoua region of central Cameroon, have suffered yellow fever, a viral disease transmitted by mosquitoes. It was enough to have seen their friends and neighbours struggle with the often-deadly infection: when a mid-April vaccination campaign was announced in their community, neither of the men hesitated.

"As soon as I learned that there was a vaccination campaign, I gave thanks to the Lord. I got myself and my family members vaccinated. I now feel well protected," said Koulagna, a father of three. He didn't stop there.

"For me, it’s health above all. Health is priceless. Yellow fever manifests itself with vomiting, diarrhoea, headaches and yellow eyes. I have already seen a neighbour suffer from this."

– Moise Hamadjida, father and teacher

"As president of motorcyclists in my area, I explained to my colleagues that the vaccine is very useful against this disease. They understood and got vaccinated," he said.

Hamadjida, a teacher, and his entire family were among the first to receive the vaccine on the first day of the campaign. "For me, it's health above all. Health is priceless. Yellow fever manifests itself with vomiting, diarrhoea, headaches and yellow eyes. I have already seen a neighbour suffer from this," he says.

Spike in cases

April's reactive vaccination campaign, which ran from the 10th to the 17th of the month, was staged with the goal of shoring up the defences of seven particularly vulnerable health districts in the Adamawa, North and South regions of the country. Vaccines rolled out to residents aged between 9 months and 60 years of age, excluding pregnant and lactating women with infants younger than 9 months.

For a week, social mobilisers and vaccinators visited homes and public places, including schools, markets and places of worship, to administer life-saving vaccines to eligible groups, and raise awareness about the importance of yellow fever vaccination. This campaign follows a surge in cases and deaths from the disease since 2023, described as a "public health emergency" by the country's Ministry of Public Health.

Yellow fever 101

For the worst-affected, the disease course is brutal. Symptoms can include fever, muscle pain, headache and vomiting. During a second, more dangerous phase, feverish patients start to bleed from areas including their mouth or stomach. Liver or kidney damage may follow; the 'yellow' in the name refers to the jaundice people often experience at this this stage. Up to half of those who enter this second phase die within seven to ten days.

We've had a vaccine since the mid-1930s, when a "live attenuated" form of the virus, known as the 17D strain, began to be tested as a vaccine candidate, first in monkeys, then in humans.

The 17D vaccine received licensing approval in 1938, and is still in use today, with more than 850 million doses distributed worldwide so far. Recommended for those aged between nine months and 60 years, a single dose leads to long-term, probably even lifelong, immunity in 99% of people vaccinated, making it one of the most efficient and effective vaccines.

Control is possible, but challenges remain, and the viral haemorrhagic disease kills some 30,000 people each year, roughly 90% of them in Africa.

Read more: Vaccine profiles: Yellow fever

Classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a country at high risk of yellow fever, Cameroon has in fact seen an increase in positive cases of this disease since 2021, with 45 confirmed cases in 2021, 41 in 2022 and 63 in 2023.

At the end of 2023, 26 health districts out of the 200 in the country were considered to be experiencing an epidemic, with 35 confirmed cases and 5 deaths, which represents a case fatality rate of 14.3%, according to the report released by the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI). To respond effectively to the emergency, the Ministry of Public Health, via the EPI, carried out a risk analysis, which resulted in seven health districts being targeted for responsive vaccination: Djohong, Meiganga and Tignère (Adamaoua region); Garoua 1, Gaschiga and Ngong (North); and Djoum (South).

Justifying the timing and choice of these districts for this campaign, Dr Eric Mboke Ekoum, who leads on the surveillance and response to vaccine-preventable disease epidemics in the EPI, described the criteria for their selection to VaccinesWork: "the low vaccination coverage against yellow fever observed around the cases during in-depth investigations; the high immune gap in these districts; as well as the high probability of spread of the disease, indicated by the presence of other suspected cases and the vector responsible for the transmission of yellow fever."

Have you read?

Moreover, the identified high-risk health districts were characterised by the presence of populations with specific needs, such as internally displaced people, nomads and refugees, who are particularly vulnerable. "There is also the existence of significant population movements within these districts, which could exacerbate the spread of the disease."

The objective in this prioritisation, according to Dr Ekoum, was to effectively allocate resources and target interventions where they are most urgent to contain the epidemic and protect vulnerable populations.

1.2 million vaccinated in seven days

The goal of this campaign was to halt the transmission of yellow fever in those seven priority health districts by rolling out vaccines to a target population estimated at 1,134,339 people. Ninety-five percent of that target group would need to be vaccinated to stop transmission, Dr Ekoum said; moreover, 95% of inhabitants would need to receive the government's health messaging.

In the Meiganga Health District, home to Koulagna and Hamadjida, the ultimate aim was to vaccinate the entire target population, nearly 165,500 people. "But I believe that if we reach 95%, we will at least be able to achieve the objective," said Dr Mohamad Anouar al Sadat, head of the Meiganga health district.

Al Sadat lauded the significant support from the population, and the relatively few refusals. "Most of the hesitancy concerns the safety of the vaccine, with all the misinformation we know about vaccination in general. But after explaining the benefits of vaccination and the safety of the vaccine, they accept," he said.

"This vaccination campaign was crucial, because we must protect the entire population, especially since we do not know the extent of the situation due to our weak surveillance system. It was also a great opportunity to raise awareness about yellow fever, search for new cases, and take the opportunity to identify unvaccinated people and catch up on routine childhood vaccinations. In 2023, we reported two cases of yellow fever with one death, which put the Meiganga health district in an epidemic situation," he explained.

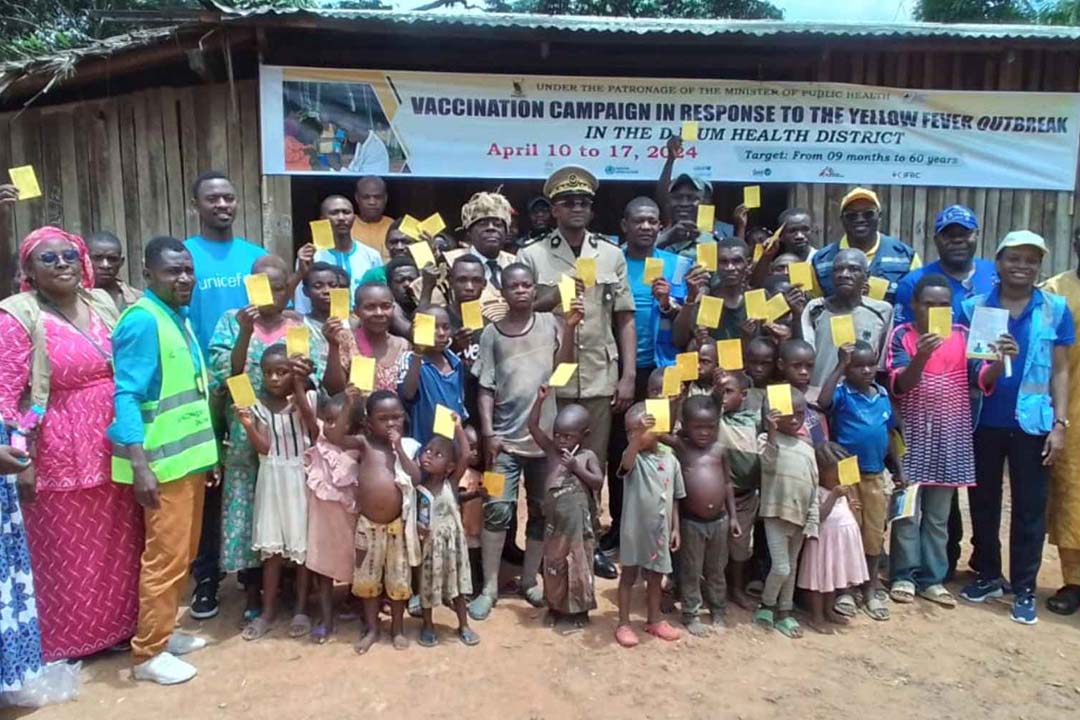

The campaign was a "total success" in the Djoum Health District in the Southern region of Cameroon, with just over 39,000 people vaccinated. According to Mr Zok Medjo Garrick Lionel, head of the Djoum health district, these figures represent 115% of the initial objective – meaning that the eligible population was in fact larger than pre-campaign intelligence had indicated.

Credit : Zok Medjo Garrick Lionel

"This campaign is an opportunity to eradicate yellow fever, and above all, to seek collective immunity of the populations of Djoum and its surroundings, especially since two borders [those of Gabon and Equatorial Guinea] are neighbours in the district," says the principal public health administrator.

"The population [turned out in massive numbers] thanks to good social mobilisation, advocacy meetings held with administrative, religious and traditional authorities, as well as community engagement meetings in all health areas," Medjo said. "The few instances of hesitancy were managed. During the campaign, we detected five suspected cases of yellow fever, which were sampled [for laboratory confirmation]."

Douala next on the list

After this campaign, the EPI plans to launch another response in the high-risk health districts of the city of Douala, the main economic hub of Cameroon and the capital of the Littoral region. This initiative aims to implement vector-control measures against yellow fever. Over the past three years, the city of Douala has recorded an increase in cases of this disease, which is "very worrying" given the geographical location of the city, warns the EPI.

"We continue to intensify surveillance activities for yellow fever throughout the national territory, and other response measures could potentially be implemented depending on the analysis of the risk of spread around confirmed cases," indicated the EPI's Dr Ekoum. "Note that in Africa, Cameroon is among the first countries exposed to the risk of yellow fever epidemics. Therefore, mitigation measures must be implemented to avoid devastating outbreaks for our populations."

This article was translated from the original French. To view the original click here.