Catching epidemics before they catch us

- 7 April 2018

- 10 min read

Global health security is under threat from a rising number of epidemics driven by a lethal mix of climate change, conflict, urbanisation and mass migration.

Preventing epidemics requires a multi-track approach: routine immunisation, preventive campaigns and emergency vaccine stockpiles.

The Alliance is working together to mitigate the risk of outbreaks on several fronts, from integrating routine immunisation and campaigns to creating the right market conditions to bolster vaccine stockpiles.

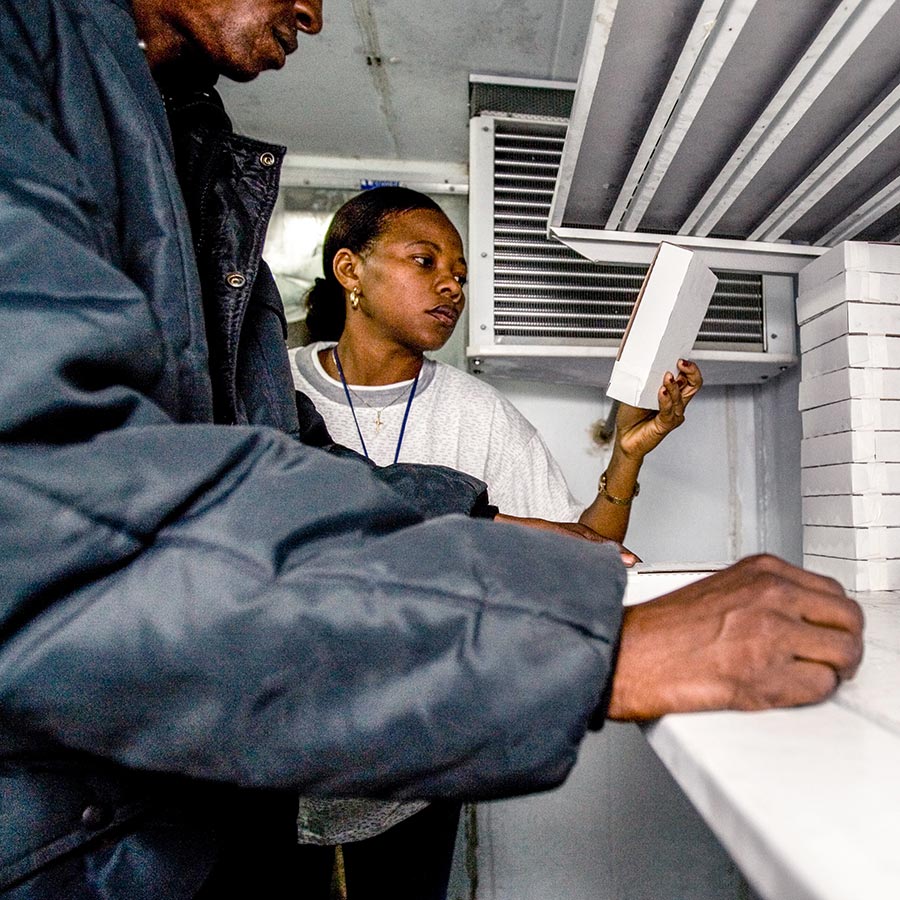

Cox’s Bazar, eastern Bangladesh

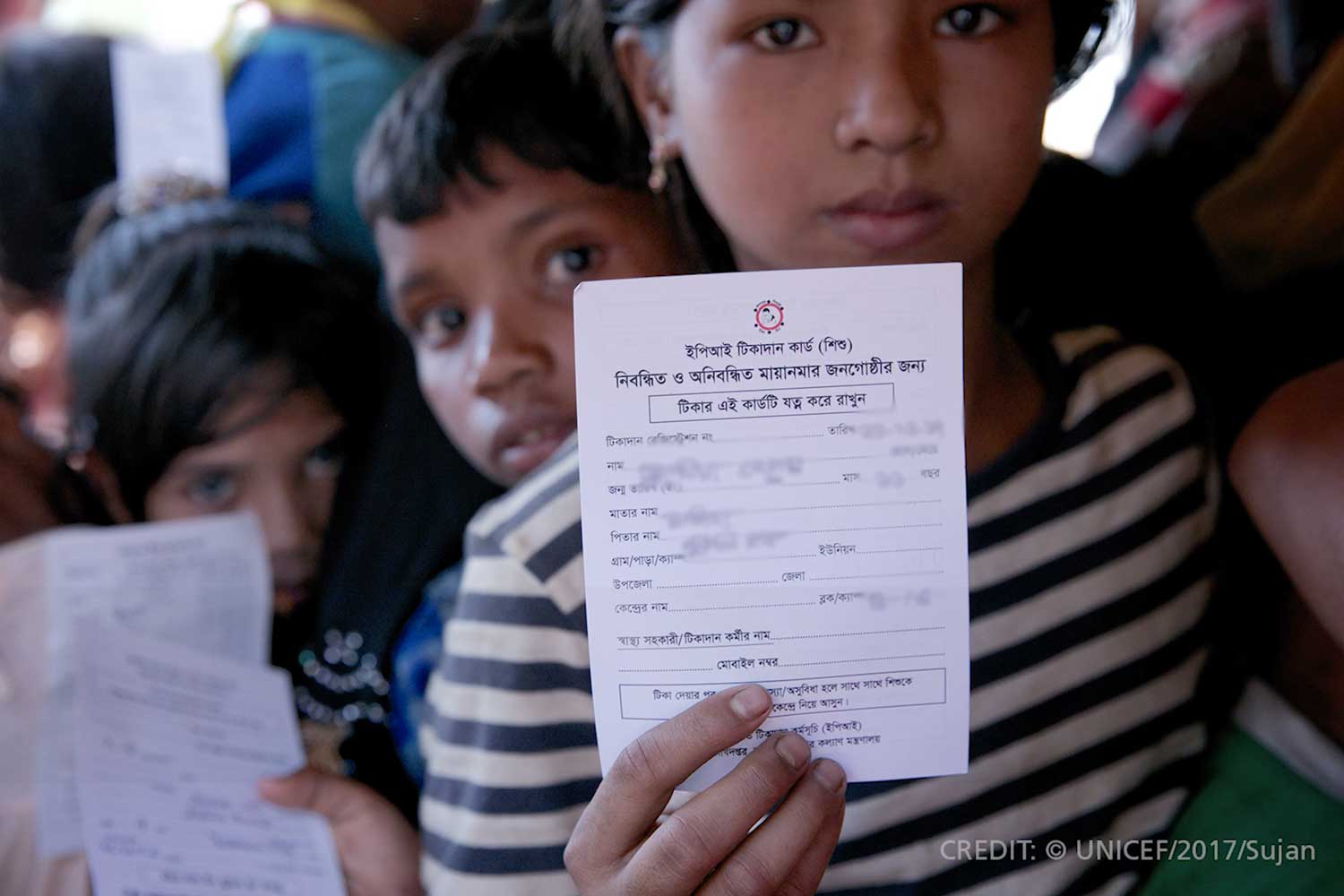

In the ramshackle, crowded refugee camp of Cox’s Bazar, in eastern Bangladesh, a young girl proudly holds a certificate. It doesn’t denote achievements in her life, but something more important. It records that her life has been protected.

She has just received an emergency vaccination against cholera, a bacterial disease that can cause stomach cramps, dehydration and death. Weeks later, she collects a second certificate. This piece of paper records she has now also been vaccinated against diphtheria, a potentially fatal respiratory disease that threatened to overwhelm the camp in which she lives, alongside thousands of other Rohingya people who have fled persecution in neighbouring Myanmar.

Each certificate also tells a wider story. The mass migration of hungry, desperate Rohingya people into Bangladesh has triggered a humanitarian crisis, and in such crises disease is often the first emergency that development agencies must face.

In Cox’s Bazar, a lack of safe drinking water and hygiene facilities, crowded living and poor nutrition quickly provided conditions ripe for contagious disease to spread. Recognising the threat, Gavi, the Bangladesh Government and other partners implemented an emergency cholera vaccination campaign that has prevented a large-scale outbreak of the disease.

But aid workers were taken by surprise when another disease, diphtheria, swept through the camp, infecting thousands of refugees. This should not have happened. In Myanmar, routine vaccination has protected more than 90% of the population against diphtheria. Its sudden appearance at Cox’s Bazar suggests the fleeing Rohingya people had been denied this protection in their homeland. So health agencies were forced to action another emergency vaccination campaign to contain the outbreak.

Gavi model in action: a holistic approach

The response to cholera and diphtheria in Cox’s Bazar reflects the holistic approach that Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance is increasingly taking to infectious disease prevention. An emergency approach will not work without a strong, long-term focus on protecting the vast majority through routine immunisation.

The diphtheria outbreak is a case in point. Given Myanmar’s high immunisation coverage, everyone in the country should have been protected through “herd immunity”. In this case it was not the cramped conditions in the camp that were to blame, but the fact that the Rohingyas had been denied their right to basic vaccination.

Gavi is implementing a range of measures to help plan for and prevent outbreaks, and mitigate their impact. The most important step is to strengthen routine immunisation and conduct preventive campaigns, but the Alliance is also funding the stockpiling of vaccine supplies and their deployment in emergencies.

The rising risk of epidemics

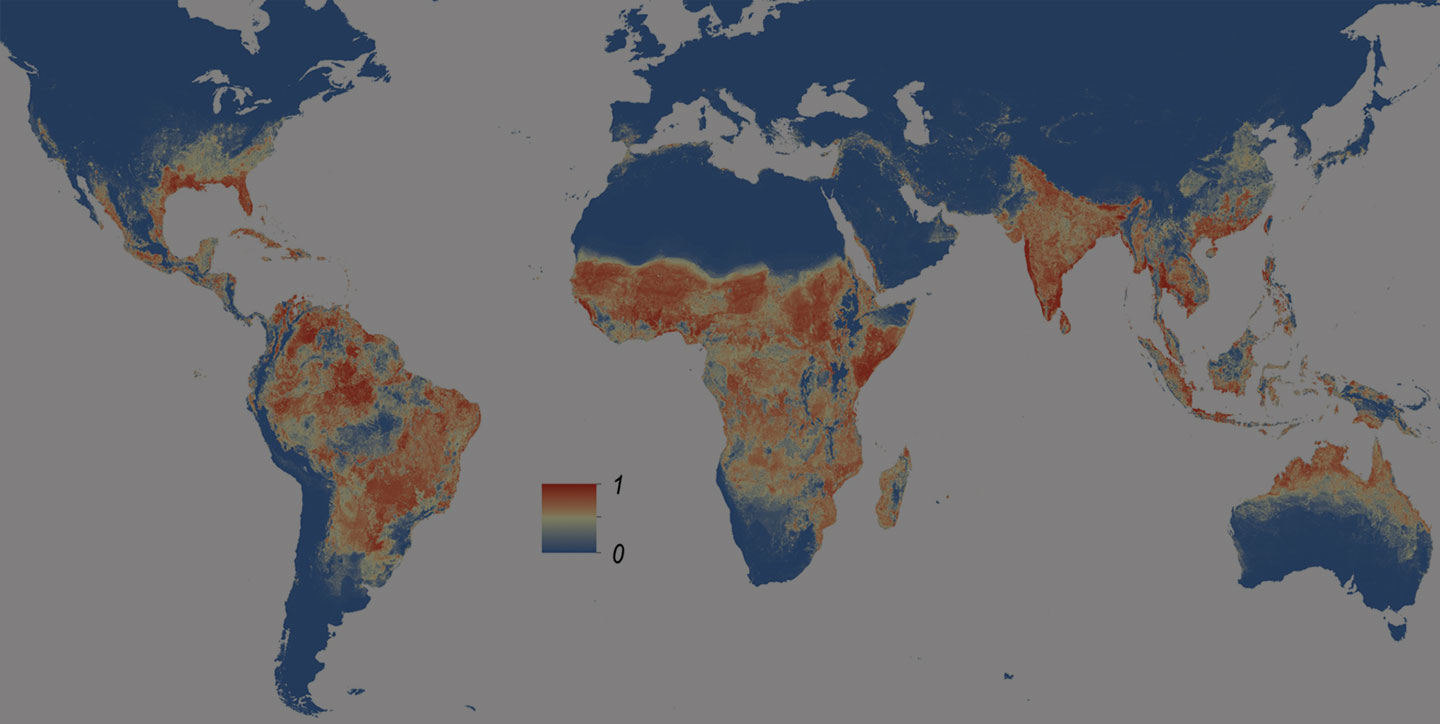

An increasing number of unexpected epidemics are emerging across the globe, caused either by unfamiliar pathogens, or known pathogens given an opportunity to flourish due to changing conditions. In recent years, these have included outbreaks of cholera, diphtheria, yellow fever and Ebola. It is becoming increasingly important to react to and quell epidemics before they take hold.

Often the emergence of such diseases is triggered by evolving pathogens or modes of transmission. By economic hardship or natural disasters, which create unsanitary conditions and compromise healthcare infrastructure and services. By wars, persecution and social instability that lead to mass migrations of people. Or by climate change, in the form of land degradation, desertification, rising sea levels and extreme weather events, and the increased risk of disease that often comes with it. With antibiotic resistance on the rise, focusing on disease prevention rather than cure is all the more important.

Gavi model in action: multi-pronged prevention

In addition to supporting routine immunisation and campaigns as well as strengthening health systems, Gavi is the sole funder of emergency stockpiles of yellow fever, oral cholera and meningitis vaccines. The Alliance has also committed to funding an Ebola vaccine stockpile once the vaccine has been fully licensed.

To ensure a rapid response to outbreaks, all Gavi-supported countries have access to stockpile vaccines free of charge and also get funding to cover the operational costs of campaigns. In 2016, the Gavi Board took a decision that allows non-Gavi-supported countries facing emergency outbreaks to draw on the stockpiles at their own expense.

And as a public-private partnership, the Alliance is working with both governments and manufacturers to accelerate the improvement of current vaccines and the development of new, more effective vaccines against both existing and emerging pathogens – and make sure developing countries are able to use them.

An effective vaccine against a deadly disease

Yellow fever is spread by mosquito bites. About 15% of people who get yellow fever develop serious illness that can lead to bleeding, shock, organ failure and sometimes death.

The yellow fever vaccine is highly effective: a single dose leads to long-term, probably lifelong, immunity in 99% of people vaccinated. Still, immunisation coverage against yellow fever is often far too low: the average routine coverage in Gavi-supported countries has not risen above 40% since 2010.

To make matters worse, rapid urbanisation and environmental changes are shifting the geography of yellow fever. In 2016, yellow fever unexpectedly broke out in Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Uganda. Thanks to prompt action and Gavi-funded yellow fever vaccine doses from the global stockpile, these outbreaks were brought under control by emergency vaccination campaigns. The last confirmed cases were reported in June, 2016 in Angola and in August, 2016 in DRC.

But yellow fever’s unpredictable spread continues. In 2017, Brazil suffered its worst yellow fever outbreak in decades. Initially affecting several eastern states, including areas where yellow fever was not traditionally considered to be a risk, yellow fever cases reoccurred in Rio de Janeiro, Minas Gerais and São Paulo. That raises the chances of the disease spreading quickly, and uncontrollably, through dense urban populations and beyond. Yellow fever has once again hit densely populated parts of Brazil in 2018, also impacting areas where vaccination was not thought necessary.

In August 2017, Nigeria detected 30 cases of yellow fever in Kogi, Kwara, Kano and Zamfara states. Within months, almost 300 suspected cases had been reported across 14 states. Gavi has funded the provision of 6.3 million yellow fever vaccine doses to control this outbreak – 3.3 million doses in 2017 and 3 million in 2018, both through the International Coordinating Group on Vaccine Provision for Yellow Fever.

These outbreaks risk a dangerous depletion of yellow fever vaccine supplies. Because yellow fever had been effectively controlled for decades, demand for the vaccine was historically low, and production limited. During the 2016 outbreak in DRC, WHO had to resort to fractional dosing of the vaccine, giving people one-fifth the usual dose, to mitigate against shortages.

As part of the Gavi Board’s 2016 decision on support for the yellow fever vaccine stockpile, Alliance funds now ensure that six million doses are always available for emergency use through a rotating stockpile.

Gavi model in action: fighting yellow fever on all fronts

In response to the rising threat of yellow fever outbreaks, the Alliance is increasingly adopting a holistic approach, including a greater degree of integration between routine immunisation programmes, preventive campaigns and an expanded emergency stockpile.

Countries that apply for Gavi’s yellow fever vaccine campaign support also have to commit to introducing the vaccine into the routine system. Gavi has been instrumental in the development of WHO's Eliminate Yellow Fever Epidemics (EYE) strategy, which aims to coordinate yellow fever control at the global level.

Gavi is working with its partners to shape the market for yellow fever vaccines.

Global demand for yellow fever vaccine is expected to continue to grow from approximately 102 million doses supplied in 2016 to 133 million doses in 2018. During its 2011-2015 strategic period, the four yellow fever vaccine suppliers and other Alliance partners worked together to increase production by investing resources in manufacturing equipment, systems and procedures. As a result, output is expected to increase in the coming years to match demand. These efforts will continue until there is sufficient buffer capacity to cope with further unexpected outbreaks of yellow fever, and the production risks of major vaccine suppliers are minimised.

Cholera affects the most vulnerable where clean water is not available

Cholera is an acute intestinal infection caused by contaminated food or water. The disease can quickly lead to severe dehydration and, in its extreme form, can be fatal. Each year, there are an estimated 1.3–4 million cases worldwide due to cholera. The majority of cases are outbreak-related, with 40–50 confirmed outbreaks every year, but many cases go unreported.

The disease affects the most vulnerable in urban slums and rural areas, where there is often poor sanitation and clean water is not readily available. Due to the quick progression of the disease, most deaths are among the poorest populations who lack rapid access to healthcare services. Cholera costs an estimated US$ 2 billion per year in treatment and lost productivity.

The successful cholera vaccination campaign in Cox’s Bazar highlights the dual role of the Gavi model in addressing outbreaks. The Alliance not only makes sure life-saving vaccines reach people in emergency situations, but also transforms markets to ensure vaccines are available and affordable for developing countries.

Gavi model in action: transforming the cholera vaccine market

When Gavi first started supporting the oral cholera vaccine stockpile in 2014, it did so with the aim of correcting a market that was not serving the poorest countries.

At that time, only two manufacturers were producing prequalified cholera vaccines: Crucell of Sweden manufacturing the Dukoral vaccine, and Shantha Biotechnics of India manufacturing Shanchol. One of these, Dukoral, was programmatically unsuitable for Gavi-supported countries as well as an expensive vaccine, costing US$ 4.7-9.4 per dose, which was mainly sold to tourists travelling from high-income countries.

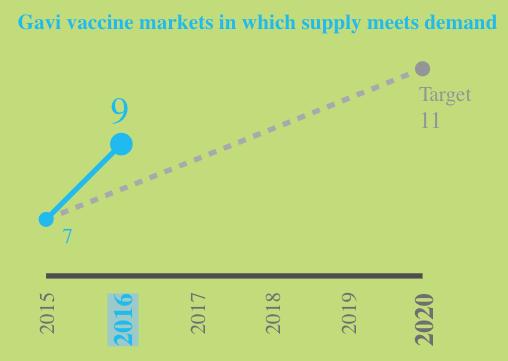

One of Gavi's many Key Performance Indicators: tracking the number of vaccine markets in which supply meets demand.

Both demand and supply were low, and, as a result, the global stockpile for oral cholera vaccine provided just 300,000 doses to countries.

Technology transfers from the International Vaccine Institute to manufacturers in several countries in Asia were key to the development of a new vaccine, Euvichol by Eubiologics in South Korea. In August 2014, the Global Health Investment Fund joined with other investors to provide additional funding to EuBiologics to support completion of their cholera vaccine efforts. Supply of Euvichol to Gavi-supported countries started in 2016.

As opposed to previous products, which were stored in glass vials and difficult to open, an updated version of this new vaccine, called Euvichol-Plus, also made by EuBiologics in South Korea, became available in 2017. The improved vaccine comes in a plastic tube with a pull tab mechanism. This not only makes it easier and safer to open, but also less expensive and more practical to store and transport.

By funding the procurement of cholera vaccines, Gavi was instrumental in breaking the cycle of low supply and low demand. By 2016, the number of cholera vaccine doses provided annually through the global stockpile had increased 10-fold to 3.7 million and reached about 11 million doses in 2017. In total, Gavi’s investment had funded 17 million cholera vaccines doses by the end of 2017.

Prevention better than cure

As a public-private partnership, Gavi is bringing together key stakeholders to forge a comprehensive global response to the growing challenge of disease outbreaks. Such outbreaks will likely only increase in the future due to rapid urbanisation, climate change, natural disasters, antimicrobial resistance, political and social turmoil, and the unplanned mass migrations of millions of people.

Immunisation has the potential to mitigate the impact of many of these risk factors by quelling disease outbreaks before they become epidemics. To do this, a holistic approach is needed, incorporating both preventive measures and emergency response and involving all partners. It also means shaping vaccine markets to make them work better for the poorest countries, and encouraging the development of both existing and new vaccines.

Rather than waiting until diseases have become a global threat, the Alliance is working to mitigate risks emerging in the first place.