Could malaria vaccination reduce childhood cancer rates in Africa?

A new study has explained the mysterious link between malaria and Burkitt lymphoma.

- 29 April 2025

- 3 min read

- by Linda Geddes

Scientists may have solved the decades-old mystery of how malaria infection triggers the development of Burkitt lymphoma – the most common childhood cancer in tropical countries in Africa.

The finding highlights the importance of malaria vaccination and other strategies to combat the infection. Not only do they reduce the risk of getting sick or dying from malaria, but they could also reduce the risk of developing this type of cancer.

“I am convinced that reducing the burden of malaria will reduce the incidence of Burkitt lymphoma,” says Prof Rosemary Rochford at the University of Colorado Anschutz School of Medicine in Aurora, US, who led the study. “Malaria control [is] cancer control.”

Blood cancer

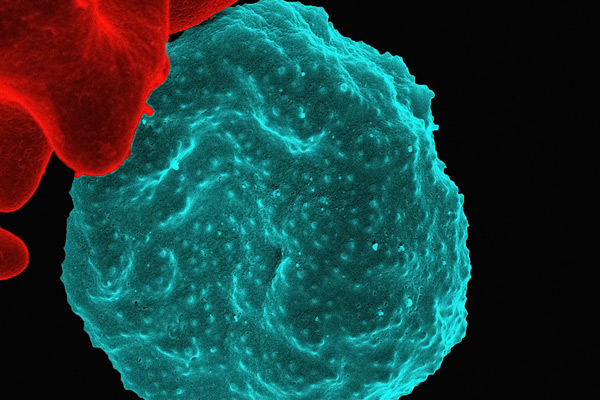

Burkitt lymphoma is a fast-growing cancer of antibody-producing immune cells called B cells, and it is universally fatal if left untreated.

It is a relatively rare cancer globally, but its prevalence is ten times higher in areas with a consistent presence of Plasmodium falciparum malaria – including many African countries.

Previous studies had suggested that effects of P. falciparum infections are cumulative, with each additional 100 infections associated with a 39% increase in the risk of developing Burkitt lymphoma. “I think of it is a steady challenge to the B cells,” says Rochford.

Even so, the mechanism underpinning this association was unclear. Rochford and her colleagues have long-been interested in how P. falciparum malaria increases infants’ susceptibility to infection with a common virus called Epstein-Barr virus, which primarily targets B cells.

Have you read?

After the initial infection, Epstein-Barr typically becomes dormant, but it can later reactivate and cause problems in a small proportion of individuals, with links to various cancers, lupus, chronic fatigue syndromeand multiple sclerosis.

Epstein-Barr infection

Rochford’s earlier research had suggested that malaria increases shedding of Epstein-Barr virus in breast milk, meaning infants are infected with it at a much earlier age when they can't control the viral infection as well. If they are repeatedly infected with malaria, as often happens in malaria-endemic countries, the number of Epstein-Barr-infected B cells increases.

So how could this increase children’s susceptibility to Burkitt Lymphoma? To investigate, Rochford and colleagues assessed blood from children with malaria, looking at levels of an enzyme called activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID).

A hallmark of this type of cancer is the rearrangement of a gene called MYC, where a piece of it breaks off and moves to another location – an event known as a translocation. The AID enzyme enables this to happen, so its production is likely to increase the risk of cancer development.

Cancer trigger

The research, published in th Journal of Immunology, found significantly elevated levels of AID in the B cells of children with malaria. “We found that malaria can induce the enzyme, and that can result in the MYC translocation,” says Rochford.

“Maybe a simpler way to think about it is a fulcrum where the repeated P. falciparum malaria infections that occur in children living in malaria-endemic regions push the balance towards more EBV-infected B cells, and finally towards an EBV-infected B cell that triggers the enzyme AID, and results in a cell with the MYC translocation.”

Reducing the burden of P. falciparum malaria in young children could therefore help to reduce the burden of this type of cancer. “Anecdotally, the incidence of Burkitt lymphoma has decreased since implementation of anti-malaria preventions,” Rochford says.

Since current malaria vaccines are designed to target the P. falciparum parasite, their introduction could further help to decrease rates of Burkitt lymphoma in malaria-endemic countries.