Delivering Vaccines in Times of War

In March 2025, Salih Basheer traveled to the Qadarrif and Galabat provinces in Sudan with Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, documenting the health workers’ commitment to routine vaccinations.

- 23 July 2025

- 6 min read

- by Magnum Photos

This story is included in a four-part series featuring Magnum photographers Nanna Heitmann, Salih Basheer, Jérôme Sessini and Newsha Tavakolian, who collaborated with Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, to document the impact Gavi-supported vaccines are having around the world. The project aligned with the 2025 Global Summit: Health and Prosperity through Immunization on June 25 in Brussels, where the photographers presented an exhibition of their work.

On a Sunday morning, mothers wait for their children to be vaccinated at the local health center in the Humra administrative district in Galabat Ash-Shargiah, Qadarif governorate. Health workers Amuna and Suhad arrived early to set up, check the refrigerators where vaccines are stored, and prepare the registers before delivering vaccines that protect children from diseases such as polio and measles.

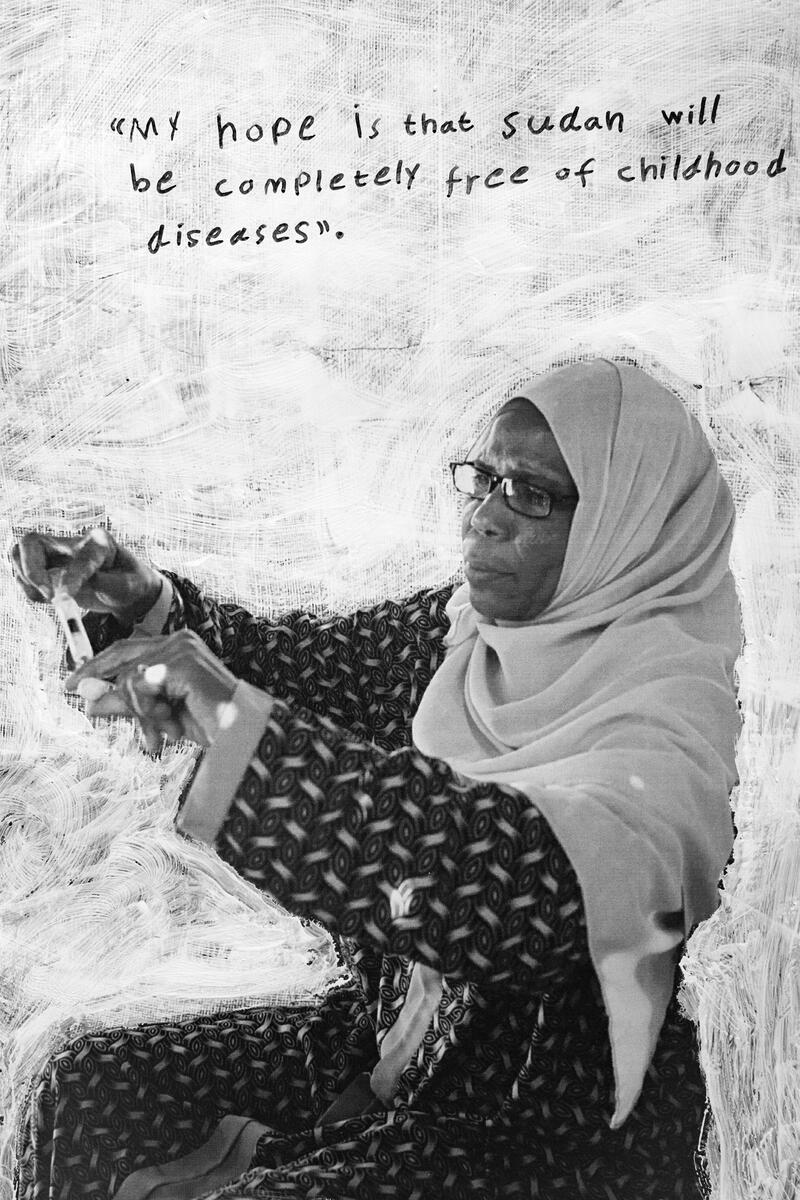

“Vaccines are about protecting our children,” said Amuna, who has been involved in immunization programs since 2008, and officially joined the center three years ago. When she sees a woman carrying her child in for vaccination, it makes her feel hopeful that one day Sudan “will be completely free of childhood diseases.” “It is such a beautiful sight to see someone going to protect their child,” she said. Amuna and Suhad are two of the many health workers who have dedicated their lives to immunizing Sudanese children against potentially deadly diseases.

In March 2025, Magnum photographer Salih Basheer returned to Sudan, his home country, for the first time since 2023. “I arrived in Sudan today, in the new temporary capital, Port Sudan, after an absence of two years. I returned on the second day of Ramadan, the same time of year as my last visit, when the war broke out during Ramadan 2023,” Basheer wrote in his diary.

On April 15 of that year, while Basheer was in Khartoum, war erupted between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), spurring Basheer to leave. “My departure from Sudan was by sea, through the same city, Port Sudan, to Jeddah, fleeing from the war at that time,” he wrote. “In the past, I used to return to Sudan via Khartoum, the city now destroyed by the war, with most of its population displaced. I would go to see my family, and all the roads I took to reach them were familiar to me and knew me. But this city now is strange to me, and I am a stranger to it.”

Basheer’s project The Return investigates his personal notion of home and the immense weight of the war. “I am still trying to process the idea of returning once again. I think it will take some time to fully grasp it,” he wrote. In January 2025, the United States officially declared that the RSF have committed genocide.

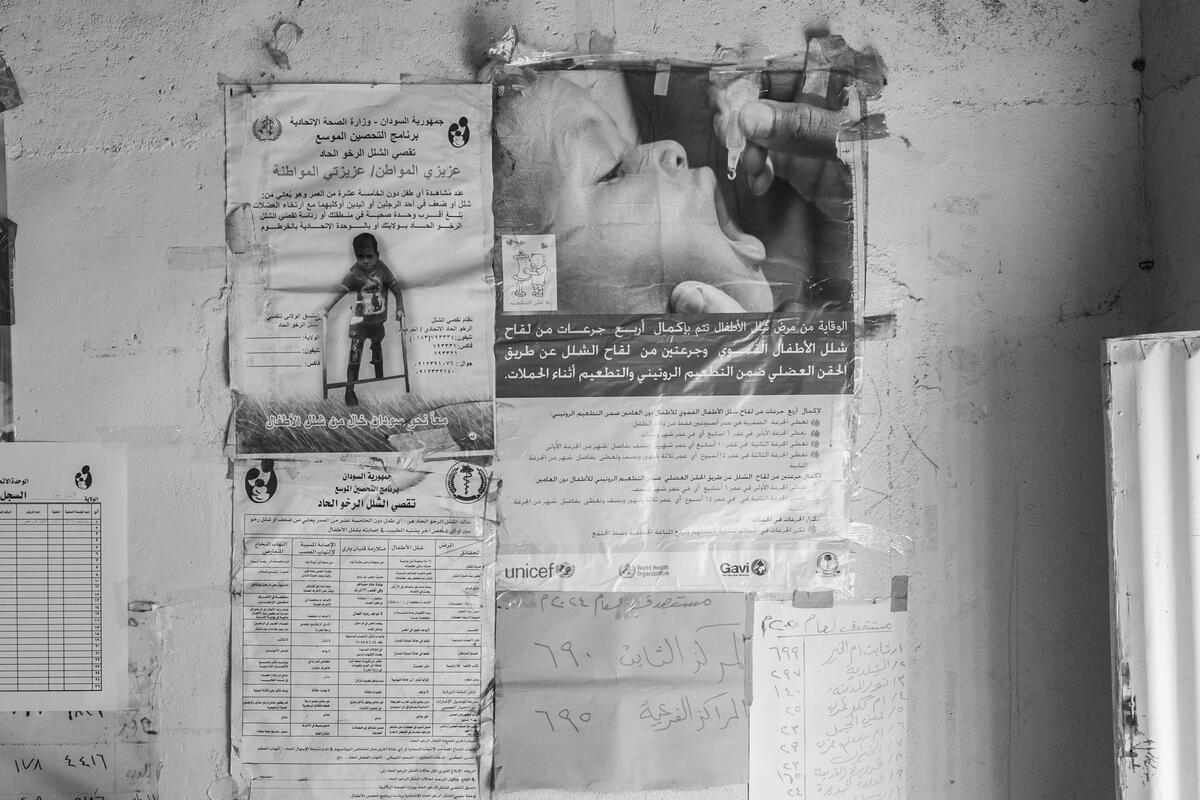

In Qadarrif and Gabala, two regions far from the centralized areas of the conflict, Basheer met health workers helping to carry out routine vaccination schedules. Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, is working with UNICEF and Save the Children Sudan to strengthen the country’s National Emergency Vaccination Plan and address the urgent need for immunization as the conflict continues to disrupt health services.

In Sudan, breakdowns in vaccine supply routes and a fragile healthcare system have impacted children’s access to life-saving vaccines that can protect them from diseases such as measles, rubella and polio. As of October 2024, 43% of children in Sudan were missing out on these essential vaccines, according to Gavi.

The surge of displaced people due to Sudan’s violent conflict has made daily tasks for health workers in rural provinces more complex, adding to the struggles they faced before the war, such as transportation, flooding and vaccine storage.

“The bigger challenge lately has been with the displaced people,” Amuna said. “They are traumatized by the war.” The Sudanese civil war has resulted in approximately 28,000 registered deaths, according to ACLED, but hundreds of thousands of deaths are estimated to be unaccounted for due to the lack of systematic records. The violence is concentrated mostly in Darfur, Khartoum, and, since late last year, south of the capital in Al-Jazirah, causing a dire displacement crisis. Over 12.4 million people have fled these regions, according to the UN, which recently called the Sudan conflict “one of the worst humanitarian crises of the 21st century.”

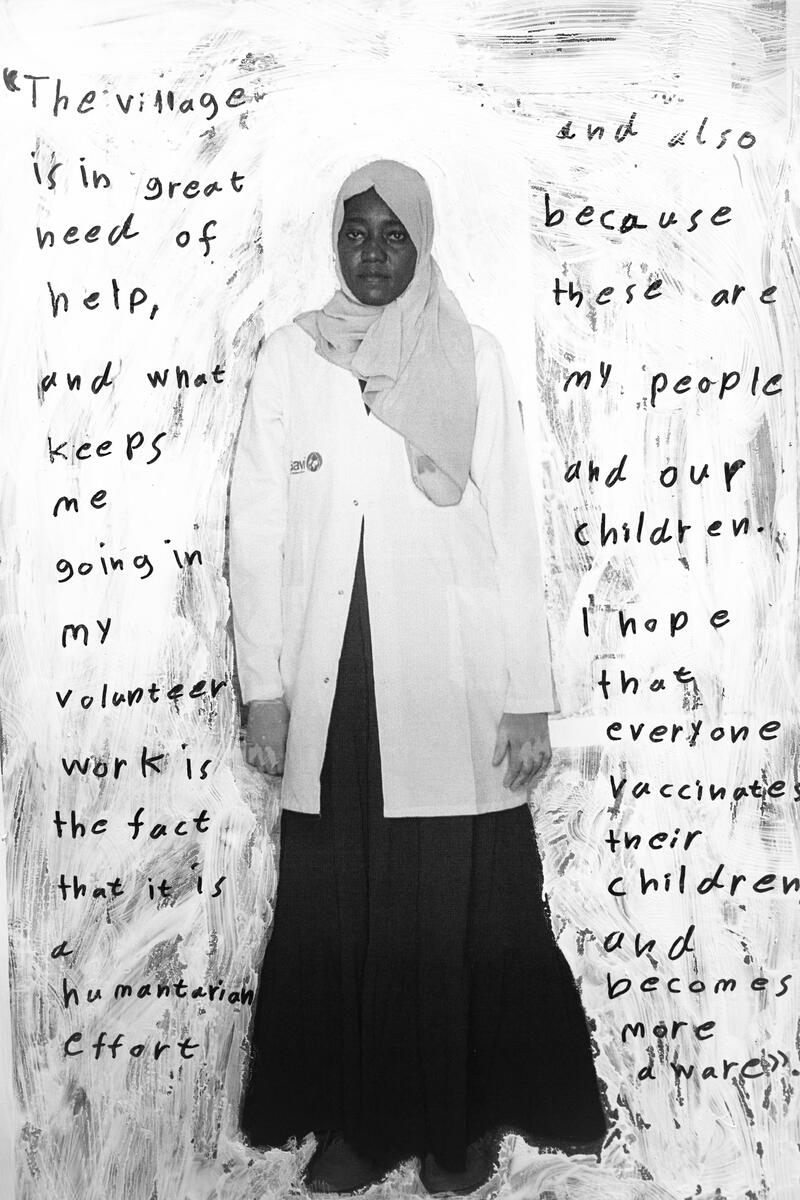

While the rise in displaced people in Qadarrif and other remote areas has increased the number of people being vaccinated, it has also made data collection and routine monitoring more challenging. To make matters more complicated, amid the escalating violence, much of the paperwork has been lost. “If the data had been digital, people could have carried it with them and tracked the records,” Suhad said.

Mass displacement has also meant that beneficiaries sometimes receive their subsequent doses at a different health center, making outreach difficult to track. During the rainy season, from about April until November, transporting vaccines proves almost impossible: “the roads are too difficult,” Amuna says, “there’s too much water.”

In Umm al-Khair located in Gedareda governorate, Dr. Al Nour carries out vaccination campaigns twice a week as a volunteer. “I don’t do the job for money,” the 45-year-old said. “I need to vaccinate children.”

When he started volunteering in 2011, the main obstacle was the population’s uncertainty about the vaccines, he recalled. Over time, through education sessions, he explained the importance of vaccination in preventing childhood diseases such as measles, polio and rotavirus, helping to improve acceptance within the community.

Despite the influx of displaced people that fled to Umm al-Khair, where they shelter in schools or homes, Dr. Al Nour reports that “vaccines are available every month and the packages come to us complete,” Dr. Al Nour told Basheer. For him, the central predicament is environmental. The campaign will have to stop before the summer months when the rainy season is at its peak, to avoid navigating floods and roadblocks.

Gavi and the International Rescue Committee (IRC) are aiming to extend the vaccination campaign’s reach to hard-to-access areas. The program would benefit from “proper transportation, at least motorcycles,” said Dr. Al Nour, adding that Umm-Al Khair’s population is widely dispersed. Because the refrigerator at the hospital where he works is currently broken, vaccines have to be sent from a center 10 kilometers away. “If we had a motorcycle, I could go and get the vaccines myself,” he said.

Amuna can empathize with this obstacle. During the summer, she needs to transport a heavy cooler to outreach locations along with the vaccination register and syringes, with no transportation. “Sometimes, I have to carry the cold box on my shoulder,” she said.

Vaccine refrigerators must be stored between 2 to 8°C to ensure their efficacy. However, as reported by the IRC and Gavi in 2024, power outages have caused refrigerators to break down, damaging vaccine supplies. To mitigate these challenges, solar-powered refrigerators and real-time inventory tracking were introduced.

Despite these adversities, the Ministry of Health, Gavi, UNICEF, Save the Children, the World Health Organization (WHO), and the Eastern Mediterranean Public Health Network (EMPHNET) have continued to work together to implement immunization campaigns, recently introducing the malaria vaccine into the routine immunization schedule, a measles and rubella immunization campaign, and a cholera immunization campaign, as well as securing shipments of routine vaccines.

“The extraordinary efforts of our health workforce have been nothing short of miraculous, providing life-saving vaccinations for our children during these difficult times,” said Dr; Haitham Mohamed Ibrahim, Federal Minister of Health in 2024, thanking Gavi for its support.

Documenting Sudan’s health situation after fleeing the crisis, Basheer was forced to confront contradicting emotions. “My feelings upon returning to Sudan once again were that I felt like a stranger in my own country, just as I do outside of it,” he wrote in his diary. “Sudan is no longer the Sudan it used to be; everything has changed. Yet, I feel warmth in being here once again among my people and in my country.”