An extremely important fridge: Keeping vaccines cool in remote Kashmir

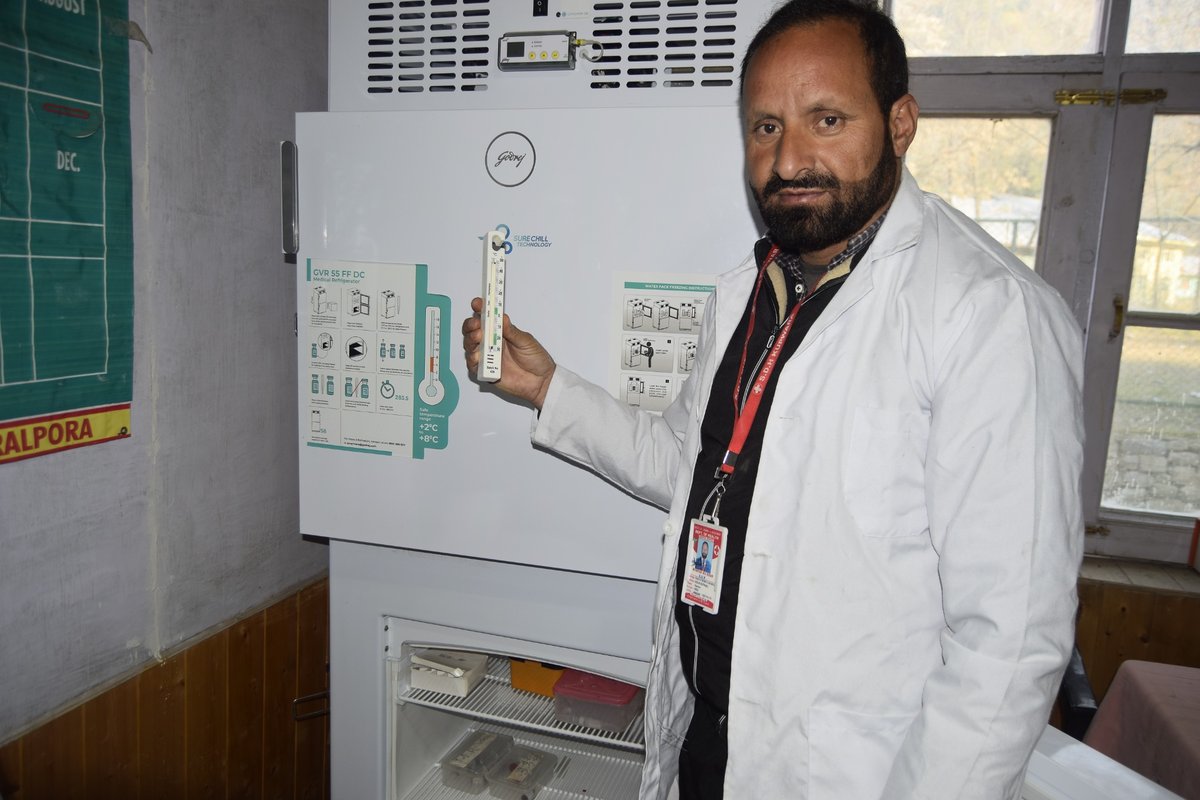

In mountainous northern Kashmir, a new solar-powered fridge is keeping local children protected from disease. Health worker Mumtaz Ali Khan is the man charged with keeping it running.

- 27 January 2025

- 5 min read

- by Nasir Yousufi

By the time the roosters crow for sun-up on a cold December day in Keran, a village perched on the northern frontier of India in the Himalayas, Mumtaz Ali Khan, aged 49, is already on his way back from his morning wash at a nearby water-spring. He has a busy day ahead.

Khan, a health worker, is also the caretaker of an extremely important fridge.

This particular fridge, specifically a solar-powered ice-lined refrigerator (ILR), is housed at the Public Health Centre Keran in Kashmir, and is the very last node on this branch of India’s sprawling vaccine cold chain.

It’s a key piece of equipment: for communities this isolated, prevention is an even higher-rated public health strategy than for their urban or plains-dwelling counterparts, and every vaccine dose administered to the people of this valley passes through it.

Prevention is better – and easier – than cure

Nestled among the snow-capped peaks and deep ravines, Keran is located in north Kashmir’s frontier district of Kupwara, about 130 kilometres from Srinagar, the capital of Jammu and Kashmir.

On the banks of the Kishenganga River, the village stands as serene as it is faraway, standing on a precipice that’s both geographical and political. Keran lies directly on the Line of Control (LOC), a ceasefire line and the de facto border on the officially still-unrecognised boundary between India and Pakistan in Kashmir.

The approximately 7,000 people who make this area their home live in eight clusters that are scattered across the slopes. The terrain makes even travel between the hamlets difficult. The most distant communities, Patru, Kandia and Naga, are as far as 10 to 16 kilometres from Keran village centre. Phone network is spotty throughout the valley, and villagers lack any proper access to the internet. In winters, the high-altitude road that connects the valley to the rest of India closes due to snow.

“In case of any acute health conditions, the villagers face a lot of problems, as patients have to be shifted to district headquarters for advanced treatment,” explains Abdul Hameed Lone, a 58-year-old resident of Naga. “We prefer to get our children and pregnant women vaccinated in time so that infections are avoided in the community.”

“Like other parts of the Kashmir, every Wednesday, the routine vaccination drive among eligible children up to five years and pregnant women is carried out in Keran and its adjoining hamlets. Apart from a team of our dedicated doctors and health workers, the last-mile vaccination in such a hard-to-reach terrain is made possible by our robust and efficient cold storage system for vaccines in the area,” said Dr Javid Iqbal Lone, Block Medical Officer from Kralpora, Kupwara in north Kashmir.

Have you read?

Looking after the ILR

After his usual two-hour walk to work, Khan reaches the health centre at about 08:00 – two hours earlier than usual.

“Today is Wednesday, and it is a vaccination day. Within half an hour, the vaccinators from all the nearby hamlets will report here to collect the vaccine. So I have reached here earlier in order to prepare for the distribution,” says Khan, counting vaccine vials in the fridge.

The appliance merits meticulous care. “Every morning, on reaching the health centre, I carry out the dusting of the ILR, check for wires, loose connections, and climb over to rooftop to clean the surface of solar plates from any foliage or dust. All this is important to maintain the efficiency of the refrigerator and its solar-powered battery,” says Khan.

The interior of the ILR must remain steadily between 2°–8°C for the vaccines – biological products, all – to remain potent.

“After checking the thermometer readings, I have to regularly record them in the temperature register twice a day in the morning and evening,” Khan adds.

Upgrade

The ILR is a fairly recent upgrade for Keran’s health establishment. Installed in May, 2023 by the Chief Medical Officer of Kupwara, with the Department of Family Welfare and Immunization for Kashmir, a vaccine refrigerator that works year-round has massively eased vaccine management in the village and its surroundings.

“Before ILR, we used to have a simple fridge which operated on the generator. Apart from being costly, the lack of fuel would often pose a big challenge to keep it going,” said Dr Mushtaq Ahmad, a senior physician who has been working in PHC Keran for many years.

“Every Wednesday, we issue 60 to 70 doses of vaccine in the valley.”

- Dr Sofi

“Many times, army soldiers from a local encampment helped us with fuel to keep the old fridge [running]. But thanks to the solar-powered ILR, the cold storage in this health centre is now running quite smoothly and comfortably,” Dr Ahmad explained.

Besides seeing to the vaccination of Keran villagers, the fridge also houses vaccines for other sub-centres in the valley. As Dr Arshid Sofi, Zonal Medical Officer, Keran, explains, vaccines stockpiled in the fridge are distributed to vaccinators from a total of eight surrounding hamlets in the wee hours of the morning. These vaccinators then take those vials – stored in insulated, passive cool-boxes – and hike to their communities to carry out vaccination. In the evening they make the return journey to bring back any unopened vials.

“Every Wednesday, we issue 60 to 70 doses of vaccine in the valley,” said Dr Sofi.

Still an uphill challenge

Majaz Khan, a panchayat (village council) secretary from Keran, said that improved cold storage facilities in the Keran area have boosted the population’s trust in the safe handling of vaccines, and helped get more children vaccinated on time.

Nargis Bano, a pregnant woman from nearby Mandia hamlet, said she is happy to have access to timely vaccination. “If we miss the routine vaccine on a scheduled day, we can easily get vaccinated on the next day at PHC,” she said.

But even though managing vaccination in the valley has become a lot easier since the arrival of the ILR, that doesn’t mean getting doses safely to these remote mountainous reaches is now hassle-free.

“Every month, I collect 600 vaccine doses from sub-district hospital at Kralpora,” explains Khan. “I usually carry these vaccines in large carrier box. But it is never easy to bring them to Keran due to lack of proper transportation. The vaccine delivery van does not come to Keran due to tough terrain. As a result, I often carry these vaccines in a public transport, but that too is very limited, as only one or two public cabs ply from Kupwara to Keran in a day,” said Khan.