Genetic ancestry linked to severity of dengue fever, study finds

Scientists have found that people with African ancestry respond to dengue infection with a quieter, safer inflammatory response than their European counterparts.

- 3 July 2025

- 4 min read

- by Priya Joi

Researchers have uncovered how genetic ancestry can influence the severity of dengue fever. The discovery that the intensity of the skin’s immune reaction can determine disease severity could pave the way for more targeted treatments and vaccines for one of the world’s most widespread mosquito-borne illnesses.

Populations historically exposed to mosquito-borne viruses, such as those in Africa, may have evolved a more controlled immune response, offering better protection against severe forms of mosquito-borne diseases

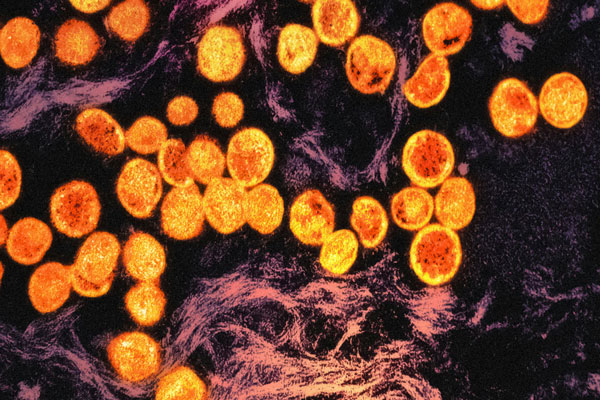

Dengue fever, often called “breakbone fever” due to its intense joint pain, is on the rise globally. The disease is spread by the Aedes aegypti mosquito (also responsible for transmitting yellow fever and Chikungunya), and climate change has meant that this insect is thriving in new habitats.

Now, one in two of the world’s population are at risk of dengue. The disease can be fatal, but its course is intensely variable, with some people experiencing no symptoms from infection, while other weather flu-like illness and recover. It’s estimated around 5% of dengue patients develop life-threatening complications such as severe bleeding, shock and organ failure.

The new study, conducted by a team of researchers from the University of Pittsburgh, UPMC, and Instituto Aggeu Magalhães, and published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, sought to determine whether there were factors predicting who that most vulnerable 5% might be. For decades, medics and scientists have traded observations that people of African ancestry from ethnically diverse countries like Brazil, Colombia, Haiti and Cuba tend to have milder cases of dengue, while those of European ancestry are more likely to develop severe disease. There had been no real clues as to why this was the case – until now.

Differing response

As with all mosquito-borne diseases that start with the insect biting our skin, the immune reaction in the skin is where the infection starts to spread.

Have you read?

The research team studied donated human skin samples from people who self-identified as having either European or African ancestry, and who had genetic markers confirming those ancestral backgrounds. These samples, maintained in culture, allowed scientists to observe immune responses to dengue virus in real time.

When exposed to the dengue virus, skin samples from individuals with higher proportions of European ancestry showed a much stronger inflammatory response. In severe dengue, this heightened inflammatory response can be harmful: skin immune cells called Langerhans cells that are supposed to fight the virus, became infected and started to migrate outwards, helping the virus spread faster throughout the body. This "friendly fire" - in which a person’s immune cells turn on the body - is believed to contribute to the damage seen in severe dengue cases.

In skin samples from people with European ancestry, dengue virus succeeded in invading a type of skin cell called a keratinocyte – which is part of the skin’s defensive system – at approximately twice the rate that it did in skin samples from people with African ancestry. Moreover, the rate of infection of keratinocytes increased with the increase in the degree of European ancestry. This suggests that people of European descent have keratinocytes that are intrinsically more susceptible to dengue virus infection.

Further experiments revealed that the key difference was not in the skin tissue itself, but in the heightened inflammatory response in the skin of people with European ancestry. When inflammatory molecules were added to samples from individuals with African ancestry, the same damaging immune process occurred – in other words, inflammation was equally dangerous to people of either background, but the dengue virus was less adept at triggering it in individuals of African background. When scientists blocked the inflammatory response in the skin samples, the virus was less able to infect cells.

Ancient protection

The findings may suggest that populations historically exposed to mosquito-borne viruses, such as those in Africa, may have evolved a more controlled immune response, offering better protection against severe forms of mosquito-borne diseases, with lowered risk of collateral damage to the body itself.

In contrast, people of European descent, whose ancestors had less exposure to such viruses, may lack this adaptation.

Understanding how genetics influences dengue severity could inform new approaches to risk assessment, outbreak management, and the development of therapies and vaccines. Future research aims to pinpoint the specific gene variants involved and further clarify the mechanisms at work.

More from Priya Joi

Recommended for you