Dengue risk in India is rising. Hard-hit communities like this one are bracing for impact

Dengue mortality rates in Pune district are expected to rise 13% by 2040, but in one village, health workers are arming the community with the know-how they need to manage that risk.

- 6 May 2025

- 7 min read

- by Sweta Daga

In the mosquito-menaced village of Karanjawane in Pune District in the Indian state of Maharashtra, a small primary healthcare centre (PHC) is betting on the maxim that an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

From the ASHA (accredited social health activist) workers who visit community members at home, to the Medical Officer, to the Pharmacy Officer, and the Laboratory Scientific Officer, the entire team is dedicated to helping the community avoid the rising risk of dengue fever. Local dengue awareness is at the point, team members told VaccinesWork, that regular citizens can identify the larvae of the Aedes mosquito, responsible for transmission of the viral disease, on sight.

“We take our special torches – phone lights do not work – and show them what larvae look like and why they need to be careful. First, we explain why storing water for long periods is not good for their health. When we do see larvae, we put medicine in that water to kill them and then we dump the water later,” says Manisha Ratan Nidhalkar, an ASHA worker with over a decade of experience.

More than 230,000 cases of dengue fever, also known as “breakbone fever” for the painful muscle spasms that often accompany bad cases, were reported in India in 2024 – a striking increase on the 157,000 cases reported in 2019.

Predicting dengue cases

A January 2025 article, “Dengue dynamics, predictions, and future increase under changing monsoon climate in India”, published in Nature explains the increase. Written by some of the foremost climate and health experts in India, it used historic data and machine-learning models to detail the link between climate change and dengue – and the potential for increased outbreaks if steps are not taken to adapt or mitigate climate change.

According to the report, dengue has emerged as the world’s most widespread and rapidly increasing vector-borne disease, with one in two of the world’s population at risk. India accounts for a third of the world’s 100–400 million infections.

The researchers say that climate change is triggering higher temperatures and changes in monsoon rainfall patterns to make Pune one of India’s leading hotspots for dengue outbreaks. Dengue-related mortality in the city is set to rise by 13% by 2040, 23–40% by 2060, and 30–112% by 2100.

Sounding the alarm

Professor Raghu Murtugadde, one of the authors of the paper, explains, “Right now, nobody has implemented an early warning system because that requires health data to train the models and also to downscale the weather forecasts. Even after we complete that – provided someone gives us data – we can only work through health agencies to issue the early warnings.”

He adds: ”The last-mile problems of getting the information to people on the street and setting up protocols for actions, like how to protect themselves against mosquito bites during the day and night and avoiding puddles of water or open drums of water, etc. to avoid mosquito breeding grounds, need to be done with health officials.”

The team at Karanjawane PHC corroborates that this pattern is evident at the local level. The medical team says that the monsoons have changed. Srikanth Darwatkar is from Sathi, a local health organisation that supports public health systems. He explains, “It’s complicated because [when it’s dry,] people struggle for water and have to walk kilometres to get it, or wait for a tanker to come so they store water at home. This breeds mosquitoes. When it does rain, it pours so badly now that water stays in small puddles for days – which means mosquitoes. Whether in drought or in rains, we have an issue with mosquitoes.”

Bharti Mali, Laboratory Scientific Officer at the PHC, says, “For us, prevention is very important. While we do our best to test and treat every patient, sometimes we don’t always have the rapid antigen tests because we only receive 100 a year from the local government. If we had that, it would make diagnosis and treatment so much easier.”

The ASHA workers go door-to-door in the drought and monsoon months to ensure that stored water is being thrown out every seven days and that when it is stored, it is covered properly. They try to spread awareness about the disease, but they concede that it takes time to build trust. They also inform people about how to protect themselves from mosquitoes during the heat or rain by wearing protective clothing and hats, and staying hydrated.

Have you read?

Checking the weather

Dr Aishwarya Natkar, the Medical Officer, says, “Awareness is required around all diseases. Our dengue cases are increasing. I would say that this year, across the three PHCs in our area, there might have been 40 cases, and on average, dengue cases have increased by 20% over the last few years. The number of cases of dengue are also unreported in private hospitals. People are stigmatised around being ill: they feel shame and don’t tell others. People think it’s something big – dengue. Sometimes they also refuse to go to the hospital to get treatment, so when patients come to the PHC or when the ASHA workers go to homes, we try our best to explain things, and many times they do listen, but then, without medicines or resources to treat them, it is difficult. I think even when a vaccine does come, it will take time for citizens to take it.”

Pune is one of India’s leading hotspots for dengue outbreaks. Dengue-related mortality in the city is set to rise by 13% by 2040, 23–40% by 2060, and 30–112% by 2100.

Dr Abhay Shukla, a public health expert based in Pune and National Co-Convener of Jan Swasthya Abhiyan, The People’s Health Movement, helps to explain the complex nature of this disease. “The spread of dengue is also propagated because of socio-ecological settings – without addressing the climate piece we can’t solve it – even with a vaccine. When one large variable changes, like temperature or rains, then peculiar phenomena take place, and you see outbreaks and it is the sections of society that are the most vulnerable that are the most affected, especially migrant populations.”

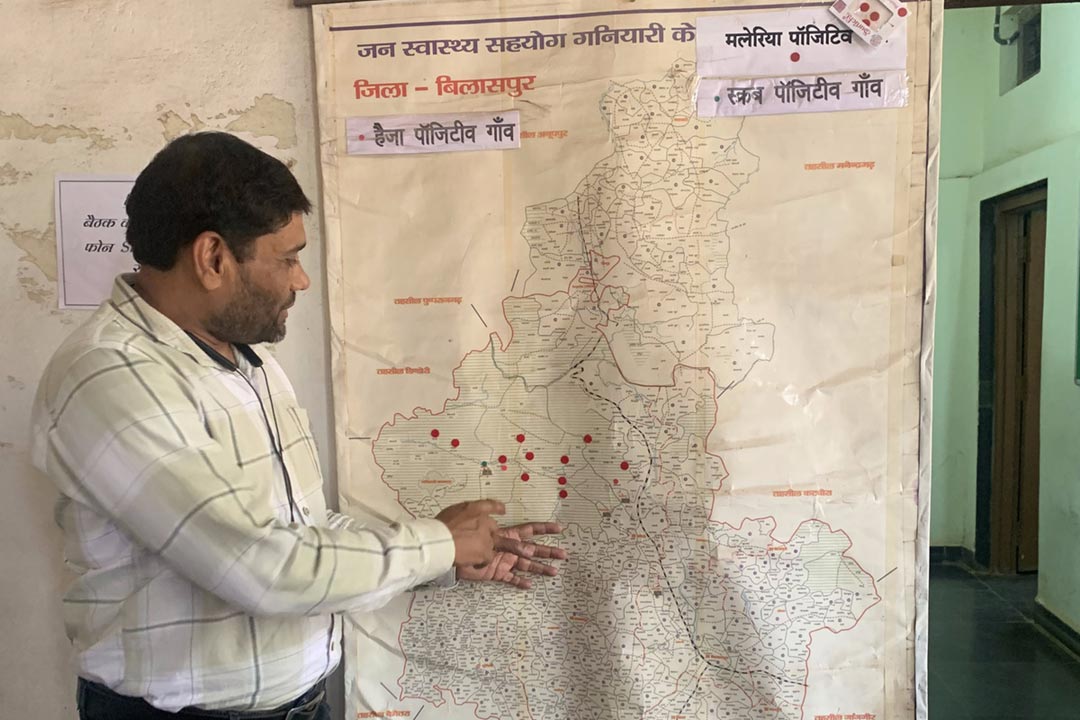

He continues, “Added to that, dengue has multiple strains and the virus keeps mutating so any vaccine has to cover all four, but I know that the Indian Council of Medical Research is doing trials. The other part of this is to strengthen our public health interventions. We need to integrate a whole set of services into PHCs – from lab services to provisions of medicines, to the latest technology. We should be mapping existing and recent outbreaks for transmission and communities that are vulnerable; for example unauthorised slums in Pune, which are not on the map of the Municipal Corporation. We need to monitor the rainfall and temperature and ensure that our frontline workers have access to that, but most importantly we need to strengthen our public health systems.”

As monsoon season approaches, the Karanjawane PHC team is preparing for the dengue season, ordering as many rapid antigen tests as possible, sometimes out of their own budgets, and making sure basic medicines are in stock.

Surendra Bhandari, the Pharmacy Officer, comments, “I never thought about warning people about weather changes – I never thought that the connection between rains or temperature and dengue was so strong – but now I will also tell them. This is also prevention. Maybe if they get the information from all of us at the PHC, they won’t feel so alone, maybe they will feel supported.”