Growing viral: health, hope, and happiness in the time of COVID and HIV

Living with one lethal virus, the children of Snehagram in southern India bolster each other in surviving the coronavirus pandemic.

- 1 December 2021

- 4 min read

- by Dr Anita Shet , Dr Michael Raj

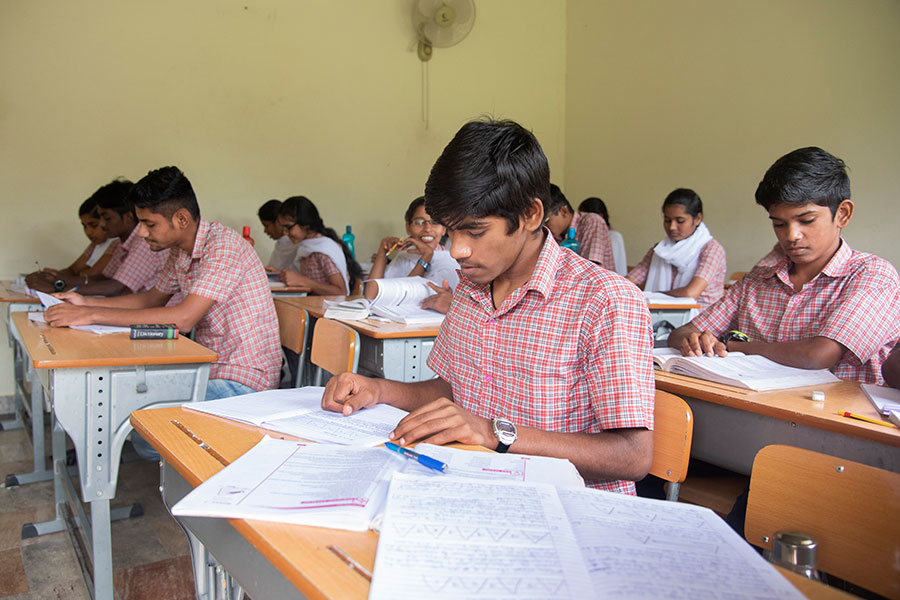

The rising sun emblazons the children doing stretches after a three kilometer run. The day begins early in Snehagram; the children have already milked the cows, collected eggs and ripe passion fruit for breakfast, and finished their morning prayers. They are fresh-faced as they troop into the schoolrooms to begin their classes.

Credit: Babu Seenappa

Tucked away among verdant rice fields and granite hills of Krishnagiri district near Bangalore in southern India, the 17-acre community of Snehagram is a residential and educational facility for HIV-positive adolescents.

“Of course, I will take the vaccine when it comes,” says 15-year-old Savitha. “For now, I dance, dream of becoming a teacher – I inspire myself to be happy.”

When the COVID-19 pandemic took the world by storm, the Snehagram children were well-prepared. They have lived with loss. Many are orphans, having lost one or both parents to HIV. Several were relinquished by their families due to the stigma of HIV. But their resilience enabled them to protect themselves, find ways to obtain daily medications, help peers get medical care, and be exemplars in COVID-19 vaccine advocacy.

Credit: Paromita Chatterjee

The residents have overcome many challenges. First of all, they had to secure access to Antiretroviral Therapy (ART), the essential salve for a healthy, HIV-free life. They know that missing even a day of these medications can mean a resurgence of HIV that can make them very sick again.

ART medicines are collected monthly from their local clinic. But the lockdown disrupted this, as hospitals became overwhelmed and closed their doors. The children’s medicine booklets, once filled by clinic nurses, are now self-maintained. Each month, they designate one youth to visit the clinic with everyone’s medicine booklets and procure medicines on time.

Credit: Paromita Chatterjee

The isolation that followed the pandemic control measures was hard. “COVID didn’t affect us physically, but I didn’t go home or see my extended family for over a year,” said 16-year-old Rajan. “I didn’t know if they had enough food to eat, or if they were even alive.”

Have you read?

Mala, a young adult peer mentor participating in the I’mpossible Fellowship, a training program for HIV-positive youth to create sustainable career pathways, initially came to Snehagram for three months. She stayed for six. “There was a complete lockdown and no buses home,” she recounts. “I continued my morning exercises, fellowship classes, and made friends for life.”

Credit: Paromita Chatterjee

On June 21, 2021, India made the COVID-19 vaccine available free of cost to all those 18 years of age and above. Days of frenzied activity followed, downloading India’s COVID-19 vaccination app, planning for vaccine visits and ensuring that everyone newly eligible – staff, students, and teachers – got the vaccine.

“The vaccine not only keeps me safe, but it also protects other children here who are too young to get the vaccine,” says Latha. Vaccine hesitancy is high in parts of Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. It is unfathomable to Latha that some refuse the COVID-19 vaccine.

Credit: Babu Seenappa

“I wish I could tell them how much harm a deadly virus can do to so many generations,” she adds. “If only I had an HIV vaccine, I would protect the whole world, and no one would suffer from HIV again.”

The younger teens are looking ahead to when they can get the vaccine.

“Of course, I will take the vaccine when it comes,” says 15-year-old Savitha. “For now, I dance, dream of becoming a teacher – I inspire myself to be happy.”

School is over for the day, and the evening game of football beckons.

Credit: Babu Seenappa