Healthcare suffers from a racial bias. What can we do to change that?

Clinical trial participants are overwhelmingly white, meaning much of our medical data has a racial bias. Here’s how we can tackle racism in medicine.

- 9 February 2024

- 4 min read

- by World Economic Forum

Different diseases present in different ways in different people. You've probably noticed how even something as common as a cold might wipe one person out, while the same strain presents in another person as just a light sniffle.

Alongside our immune system, how we are affected by diseases depends on a complex interplay between a number of factors – from our age and gender to race and genetics. So it stands to reason that the drugs to treat these illnesses might also have variable effects depending on the individual taking them.

But despite this, many of the medicines we use today have been tested on a very homogeneous group of people – mainly white and male. And the risk factors and disease dynamics that affect many minority groups continue to be underplayed with racial bias permeating the healthcare system.

Race and clinical trials

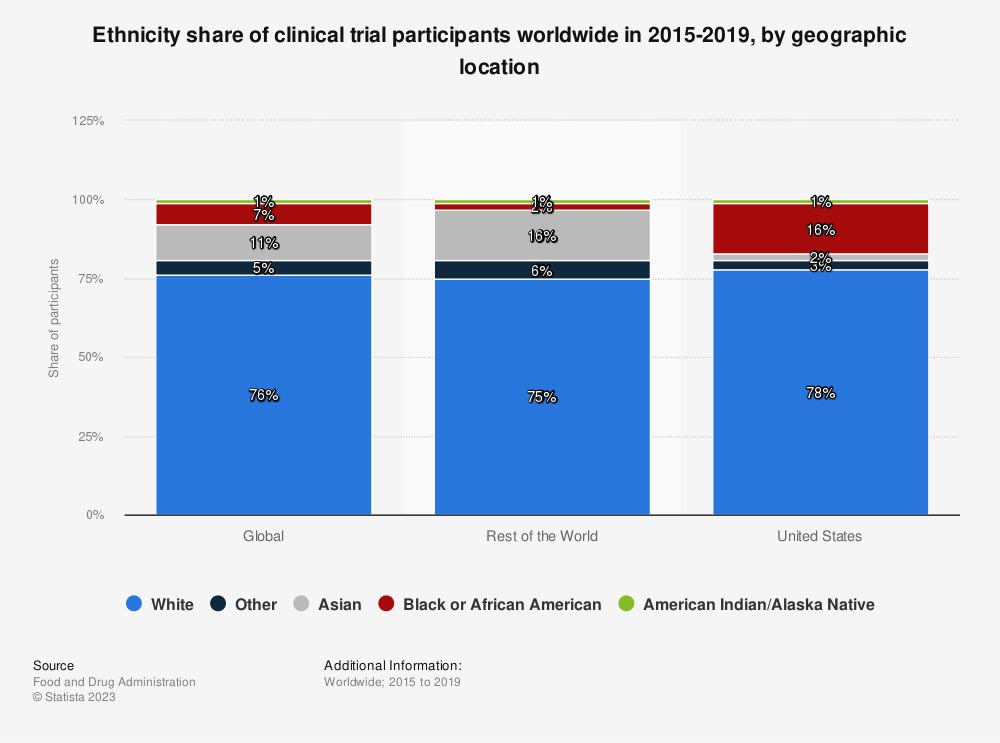

One study of oncology treatment clinical trial data, for example, showed that 62% of participants were white (rising to 84% in the US). Black and African-American people made up just 7%; Asians 3% and Hispanic/Latino fewer than that. This clearly is not representative of the global population as a whole – and is despite the fact that genetic and molecular differences between individuals cause the same cancer to present differently, for example.

Another meta analysis found that of over 20,000 clinical trials in the US, just 43% reported any race or ethnicity data at all. And among those that did, around 8 in 10 participants were white.

Diversity in clinical trials is crucial to overcoming healthcare disparities and improving equity. Properly testing the efficacy and safety of the medicines we take relies on trial participants being reflective of the populations affected by the disease.

Some diseases disproportionately impact certain groups of people, including racial and ethnic groups. This means that both the disease epidemiology and the disease burden need to be considered when designing clinical trials.

Image: Statista

Race and the future of medicine

But the impact of race in healthcare extends beyond drug development. Racially biassed data can also affect the ‘training' of artificial intelligence models, which are increasingly being leaned on for medical decision-making.

Have you read?

Studies have also shown that AI can predict patient demographics, including race, from medical images. While this has led to concerns that AI could exacerbate health disparities, there is also an opportunity for these systems to enhance patient monitoring for risk factors connected to race, as well as identify new risk factors.

Alongside this, the growth of increasingly personalized and precise medicine also necessitates a better understanding of diseases, their treatments – and how different populations are affected.

The World Economic Forum's Global Health and Healthcare Strategic Outlook sets out a vision for equitable healthcare delivery in the future, including short- and medium-term goals public and private stakeholders can take to prepare healthcare systems for future challenges.

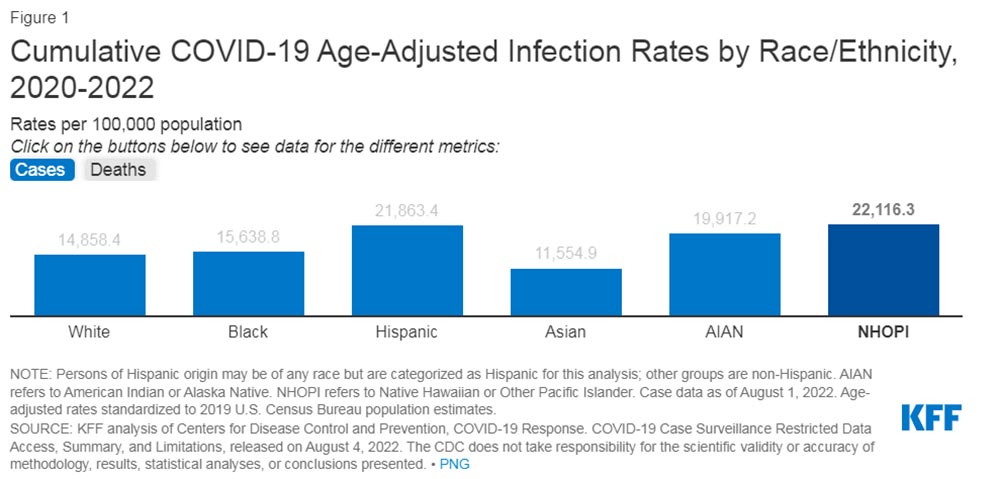

Image: KFF

Lessons from the pandemic

The pandemic also provided us with plenty of examples of how race affected the outcomes and treatment of many individuals.

For example, pulse oximeters – the devices which measure blood oxygen levels through fingertips – were shown to be less accurate when used on Asian, Black and Hispanic patients compared to white patients. This contributed to delays in diagnosis or access to COVID-19 therapies.

And then there are population, occupation and cultural dynamics connected to race and ethnicity which also meant that the health impacts of COVID were unequally felt. For example, the London School of Economics pointed to the fact that minority groups in the UK are more likely to live in densely populated areas or large family groups, compared to white people, which contributed towards disease spread. The researchers also pinpointed a greater likelihood of having an additional health condition which complicated COVID infections, particularly among some groups such as Bangladeshis.

Image: BMA

Racism in the workplace

It's not just patients who experience racism in healthcare – it is also widespread within the medical workforce. Over three-quarters of respondents to a survey by the British Medical Association said they have experienced racism in their workplace at least once in the past two years.

Many doctors feel that racism has held them back in their careers, as well as affected their confidence and physical and mental wellbeing.

Personal bias in the recruitment of the medical workforce can also hamper the ability to create a healthcare system which is representative of the population it serves, another study highlights.

The Global Health Equity Network was launched in September 2021 by the World Economic Forum, and is aiming to make progress on a standardized way of measuring and describing health equity. It will highlight examples of where institutions have made progress with a view to driving action more broadly.

Written by

Charlotte Edmond, Senior Writer, Forum Agenda

Website

This article was originally published by the World Economic Forum on 8 February 2024.