How creative communication strategies are helping fight COVID-19 misinformation in DRC

The misinformation surrounding COVID-19 in the Democratic Repubic of the Congo isn’t new – public health officials have seen rumours and myths circulate with Ebola. Here’s how they are tackling them.

- 4 August 2020

- 8 min read

- by Gavi Staff

It is in the nature of an epidemic to trigger fear, sometimes causing misinformation to spread even faster than a virus. In this context of “infodemic” – a term that first appeared during the 2003 SARS outbreak – the lack of good information can lead to false rumours. Misinformation deeply affected the effectiveness of the health response in West Africa and Liberia during the first Ebola outbreak in 2014.

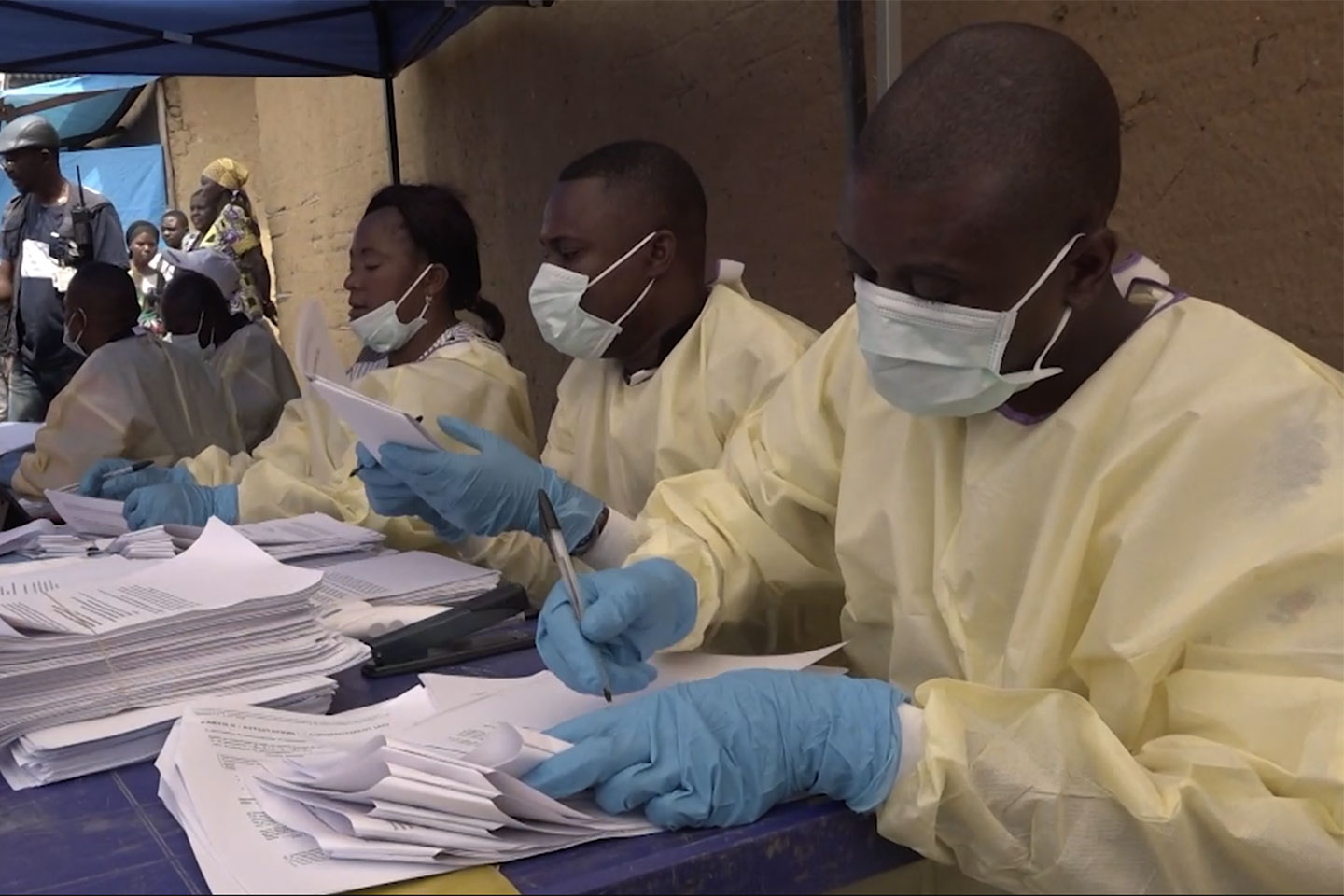

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is also no stranger to this problem, since it has been dealing with misinformation since its Ebola outbreak started in 2018 in the east of the country. Misinformation as well as social distrust towards the public response had led to several attacks on health workers and Ebola centers in North Kivu.

Now, DRC is also facing the same challenge in response to the COVID-19 global pandemic. The government and its partners have launched a Risk Communication and Community Engagement (RCCE) strategy, to address growing misinformation by raising awareness through a variety of channels.

From Ebola to COVID-19 sensitisation

In February 2020, the first countries in the African continent begin to be affected by COVID-19. After months of posting prevention messages regarding the Ebola outbreak raging in North Kivu on its Facebook account, UNICEF in DRC began communication on the novel coronavirus. Hundreds of comments left on their page showed that a lot of people think the virus only affects rich or white people, or is a conspiracy from the western world. One month after that, DRC identified its first COVID-19 case. Since then, the number of cases has grown rapidly to reach close to 9,000 cases, and the wave of misinformation has grown as well.

In order to accurately fight these rumours, it was important to first understand where they originated and who was perpetuating them. This is the strategy the Congolese government and partners have decided to follow by developing a community feedback system to find out what rumours are circulating in the country, and how they spread. The answer to these questions lies with the community. They have shared their perspective via social networks, a UNICEF-reporting platform (surveys collecting data via SMS), and investigations of rumours within communities. A Covid-19 hotline supported by UNICEF has already registered 75,065 calls, with an average of 3,951 calls per day. The majority of the calls are from individuals requesting general information on COVID-19.

Dangerous rumours circulating

According to UNICEF’s communication unit in Kinshasa, the most dangerous rumour on social media is that people refuse to believe that the COVID-19 exists in DRC and that it can kill people. This is supported by the findings of a survey by the Kinshasa School of Public Health, which highlighted that 20.2% of people interviewed in the capital did not believe that COVID-19 is real.

Immunisation is also plagued by misinformation. Data from a UNICEF opinion poll have brought to light two main rumours circulating in DRC regarding routine immunisation and vaccines in the COVID-19 context. The most prevalent is the fear that the country could be used as a laboratory for a COVID-19 vaccine trial, in which people are injected with a dangerous trial vaccine instead of “safe and proven” vaccines like the one against measles. The second rumour is that vaccines in general are poisonous. The development of effective communication to combat these views and reassure people about the merits of a certified COVID-19 vaccine will therefore be key to ensuring the timely and effective deployment of this vaccine.

In Kinshasa, the average number of children going to an immunisation session dropped by 10% between March and April 2020. Although the exact impact of misinformation cannot yet be precisely quantified, it most likely played a role in discouraging some parents from having their children vaccinated. According to the opinion poll, in Kinshasa, 80% of respondents who were exposed to rumours are parents of children targeted by the Extended Programme on Immunisation (EPI). 78% of them say these rumours have had a negative impact on their will to vaccinate their children.

To address context-related challenges, different communication strategies are implemented by the government and its partners. They tend to diversify their approach using the same channels used to spread false information, hoping for good information to take the upper hand. They believe that by sharing accurate information to tackle misinformation, they can help increase confidence in future COVID-19 vaccines.

Mass media communication

According to UNICEF in DRC, more than 29 million people have been reached with key messages on how to prevent COVID-19 through mass media channels. 341 radio stations and 65 TV channels have broadcasted prevention messages and specific COVID-19 shows in the most affected provinces. Because radio is the most accessible media in DRC, this strategy allows UNICEF to reach an important part of the population in the whole country.

In addition, the Ministry of Health’s EPI team, with support from UNICEF and Gavi, launched a communication campaign to promote routine immunisation between June and July 2020. It included interactive radio shows that highlighted key messages about the safety, security and efficacy of vaccines. The EPI team, also recognized and leveraged journalists as key communication partners to relay f good information. During a briefing organised for the launch of the campaign, EPI Director Dr Elisabeth Mukemba urged journalists to avoid spreading misinformation but rather to emphasise the benefits of routine immunisation in order to restore parents’ confidence and thus keep protecting children against vaccine preventable diseases. This communication effort is likely to have contributed to a 7% recovery in immunisation attendance between April and May in Kinshasa (data from Acasus partners in Kinshasa).

The challenges of digital communication

Social networks are also an important channel to target rumours, enabling communication specialists to hear the voice of the community. Indeed, after receiving hundreds of comments asking for pictures and proof of sick people from COVID-19 in DRC, UNICEF communication specialists broadcasted interviews of patients in treatment and recovering from COVID-19. They also post daily situational reports, videos, infographics or text messages designed to sensitise the population on COVID-19, and/or promote routine immunisation. According to them, the main rule of efficient communication is to produce easily shareable content. Even if videos are considered more effective, text messages and press releases reach a wider part of the population, as internet access in DRC is expensive and the free Facebook app only displays text.

To this point, it is important to remember that today only 10% of the Congolese population has access to the Internet. Among them, only 3% to 5% are connected to social networks, which shows the need to complement this approach with other means of communication.

The power of word of mouth

Word of mouth has always played an important role in DRC and it is the main way that rumours are spread, according to the UNICEF opinion poll. Engaging with community influencers to spread good information and adapt the response to different populations is an important part of an effective communications strategy.

In addition to the traditional prevention messages on banners and posters spread in the streets, specific communication activities are organised within the RCCE strategy. In Kinshasa, the Civil Society Organization SANRU is launching sensitisation activities in every health area, with support from Gavi and other partners. Town criers shout messages related to COVID-19 prevention and promotion of routine immunisation in the town’s avenues. This a common way of communicating with communities in DRC and can help ensure that a large number of people are reached with accurate, relevant messages.

In the coming months, the EPI team will lead creative outreach activities like street and online sketches on routine immunisation featuring popular theatre groups. Within this campaign, visits to religious leaders and influential village chiefs, along with health technicians are also planned. These groups are critical conduits of information in the communities, where they are respected and listened to.

That said, community outreach channel may be hampered by COVID-19 safety measures. Indeed, the prohibition of gatherings of more than 20 people as well as physical distancing rules are complicating the work of community social workers. Furthermore, in DRC religious leaders carry a high degree of trust and influence in their communities, however, the closure of churches means that EPI managers can no longer rely on religious leaders to share key messages.

This means that home visits are the default option for community outreach, which limits its reach and poses infection risks for health workers.

Can good information tackle misinformation?

In the midst of an uninterrupted flow of information, it can be challenging for people to know what the facts are. Even when the right information is acquired, it does not always translate into the expected behavior. The Kinshasa Public Health School’s survey showed that in the capital, if prevention measures are well known, their level of practice remains low. Only one in five of those interviewed showed a willingness to comply with the measures outlined by the government to avoid contracting COVID-19. This might be explained by the negative economic impact these measures tend to have on population, which makes them less inclined to adhere to guidelines.

One of the major challenges in the coming months for the DRC therefore lies in the capacity of these communication strategies to reach and impact as many people as possible, so that awareness-raising, combined with other measures, can help stem the spread of COVID-19.