Masking Trouble

As the Spanish flu of 1918-1920 tore through America, a San Francisco mayor bet on the potential of face masks to contain the spread. Then, like today, the demand to mask up met resistance that blended distrust, ideology and gut feeling.

- 12 May 2021

- 5 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

At noon on 21 November 1918, when the pandemic Spanish flu appeared to be at an ebb in San Francisco, a whistle blew. The streets erupted in celebration. Men and women yanked off their face masks, and, as the San Francisco Chronicle reported, threw them to the ground and stamped on them. The whistle signalled the expiry of a month of “muzzled misery” – the Mayor’s Mask Ordinance. Some midday revellers hammed up their relief, the Chronicle’s writer observed: they mimed breathlessness, ordered up celebratory drinks to toast their regained freedom. The outbreak, by then responsible for well over 1000 deaths in the city, was described as “virtually over.”

But during the subsequent months, a second wave broke over San Francisco. From 50 new infections a day in late November, the case-count ticked up quickly. By New Year’s Eve, San Francisco was recording 540 new daily cases, and 31 deaths. By early-mid January, the hospitals were drowning. Before the pandemic ended, 45,000 San Franciscans were infected, and more than 3500 were dead.

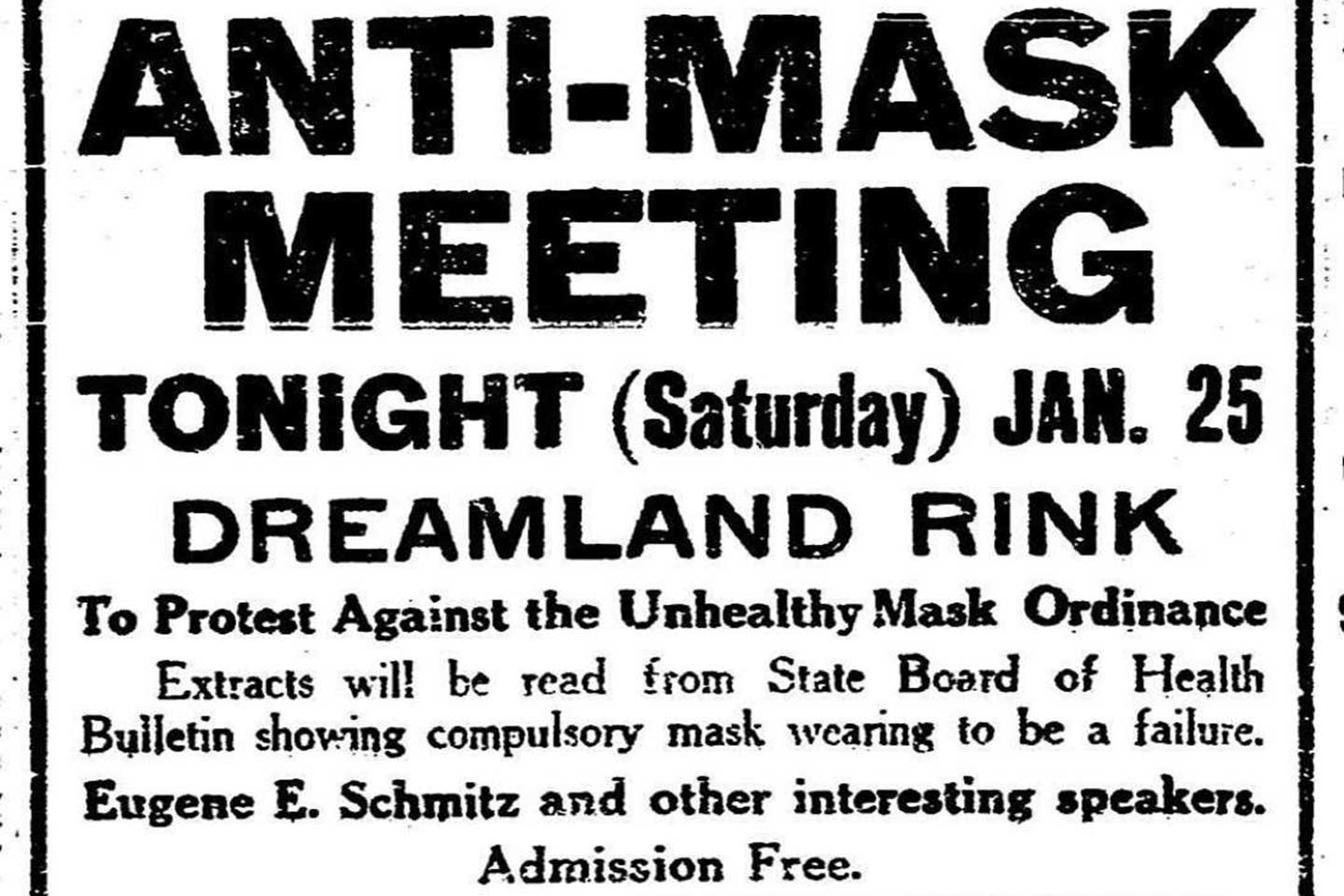

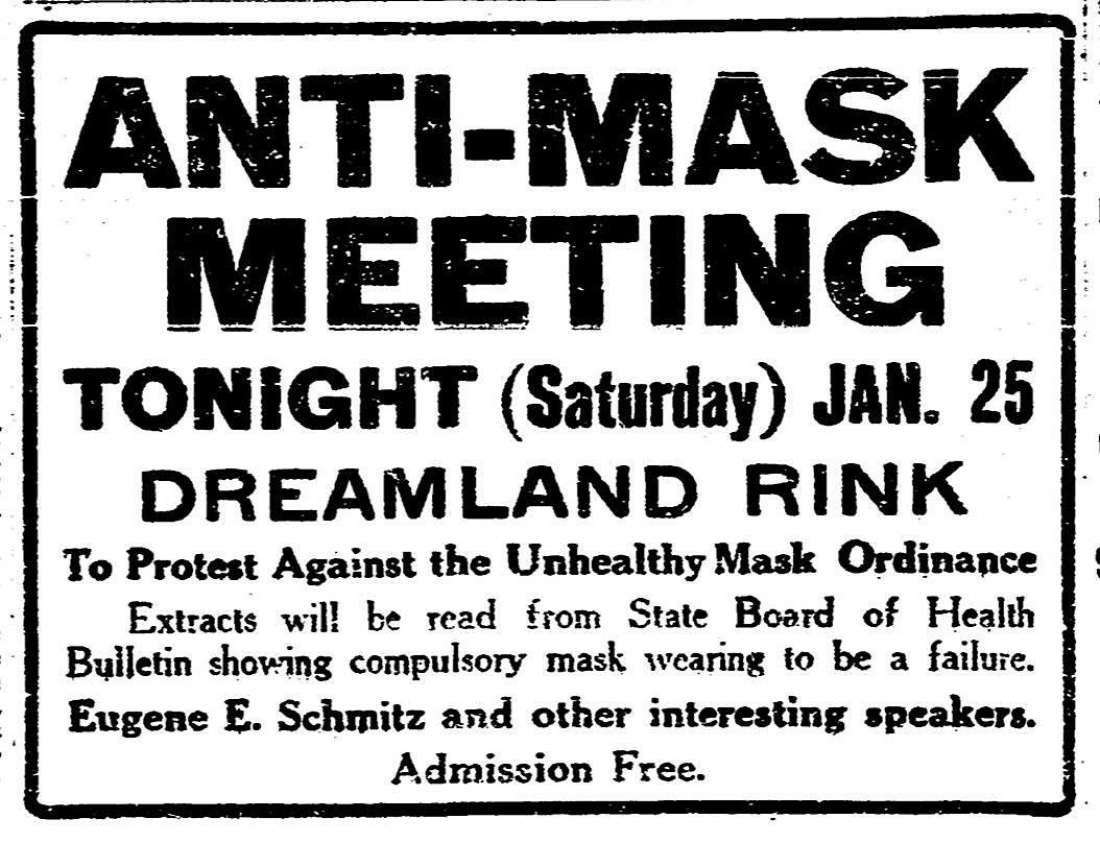

On the 9 January 1919, the city Board of Supervisors voted 15-1 to make masks mandatory again. Soon after, San Francisco’s Anti-Mask League was born at a protest meeting which attracted thousands.

Credit: SF Chronicle

The deadly Spanish flu – which would kill at least 40 million people worldwide, and perhaps twice that number – had been spreading in the United States at least since March, when it tore through an army barracks in Kansas. According to newspaper reports, in October 1918, a man returning from a work trip to Chicago brought the virus home to San Francisco. It spread fast. By month’s end, city health authorities logged 20,000 cases.

Have you read?

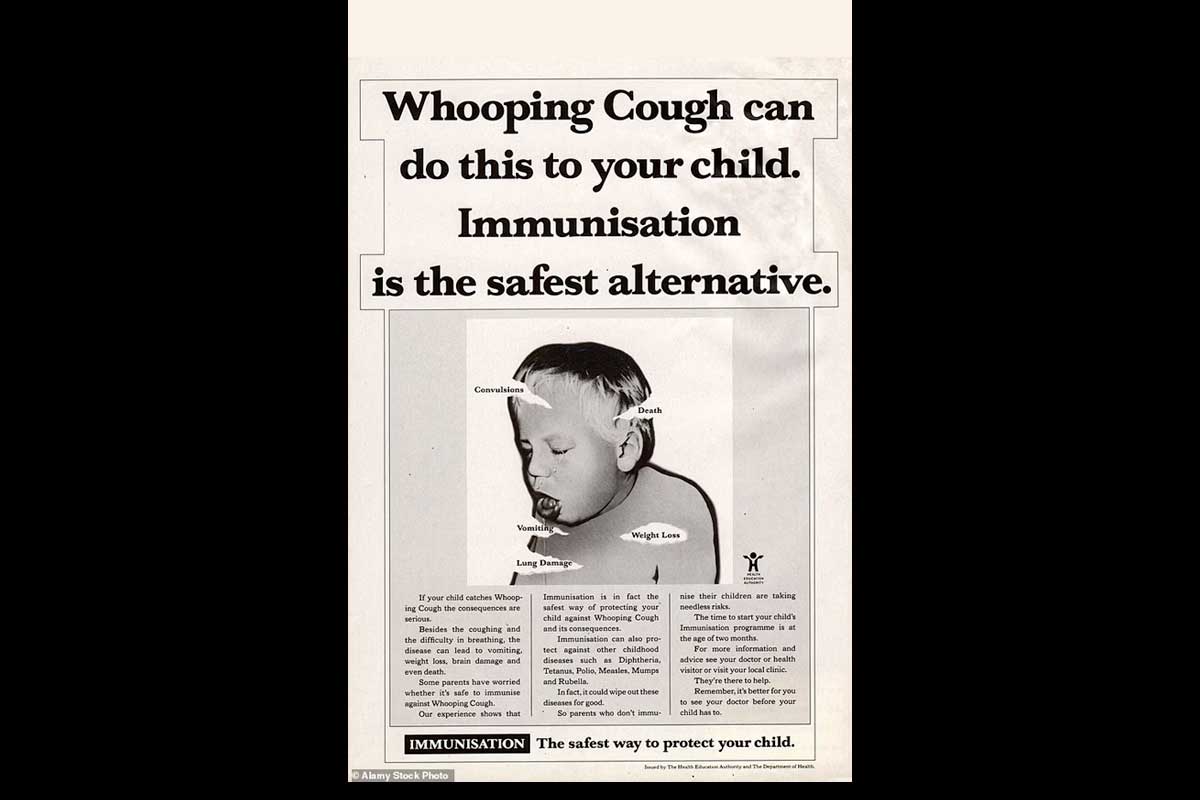

Dr William Hassler, chief of the City’s Board of Health, called for short, sharp shut-down: schools and public amusements were closed on 18 October 1918. On 22 October , a Mask Ordinance stipulating a 4-ply mask made of gauze or cheese-cloth, was announced. This was wartime; the language of patriotism and sacrifice was everywhere. California governor William Stephens called the wearing of the mask “a patriotic duty”. “Dangerous slackers,” as one American Red Cross public service announcement termed refusers, were fined between $5 and $100, or briefly jailed.

People grumbled – masks made you look “piglike” or spooky, they seemed intuitively unhygienic, they were uncomfortable; did they even work? – but, for the most part, the public co-operated. As Dr Howard Markel, a historian of epidemics, told the New York Times last year, organised resistance to mask-wearing was hardly the norm.

The Anti-Mask League was, then, a notable exception. About a week after the mask regulation was re-instated in January 1919, the League attracted a turnout of 4,500 people at a public meeting at the Dreamland Rink. Who were these San Francisco anti-maskers? Some prominent opponents of the orders to mask up included businessmen whose profits had been hit by the shut-down. Others were citizens, such as a Mrs CE Grosjean, appalled by Dr Hassler’s “domination” – at Dreamland, the Anti-Mask League distributed petitions calling for the public health chief’s dismissal.

Attending the Dreamland meeting were doubters of the capacity of masks to manage the bug: “what doctors don’t know about this epidemic of influenza would fill a decent-sized library. And yet they have the ‘gall’ to force us to wear masks?” someone wrote to the San Francisco Chronicle that month. Others wrote in of their conviction that wearing masks was tantamount to breathing “foul air.” The League’s President was Mrs E.C. Harrington, lawyer, suffragette and talented public speaker, an important voice in the successful struggle for women’s votes in San Francisco. According to medical historian Dr Brian Dolan, Harrington’s broader activism placed her in opposition to the Mayor who had enacted the mask mandate – a reminder that no movement is a pure referendum on its stated issue; that all campaigns are caught in political cross-currents.

Today’s anti-maskers are also often mistrustful of public authorities. There are those who make mask-wearing their bellwether of covert constitutional erosion. To some, the mask represents an insult to religious faith; to others, it marks an assault on ostensibly imperilled rights. But there is an important difference between today’s anti-maskers and 1919’s. During the Spanish flu pandemic, evidence for the efficacy of mask-wearing was patchy at best – the masks, as they were designed and worn then, had not been proven conclusively to suppress spread (though social distancing measures had evident impact).

Today, we have the benefit of greater certainty: better masks, and better data to show that they work. And though a noisy minority continue to cry foul, for most of us, masks, like vaccines, are an easy bargain to strike: a temporary discomfort to save lives; an ethical no-brainer.