Whooping cough: a history

The scientists who fought pertussis, and what they lost before they won.

- 5 August 2025

- 13 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

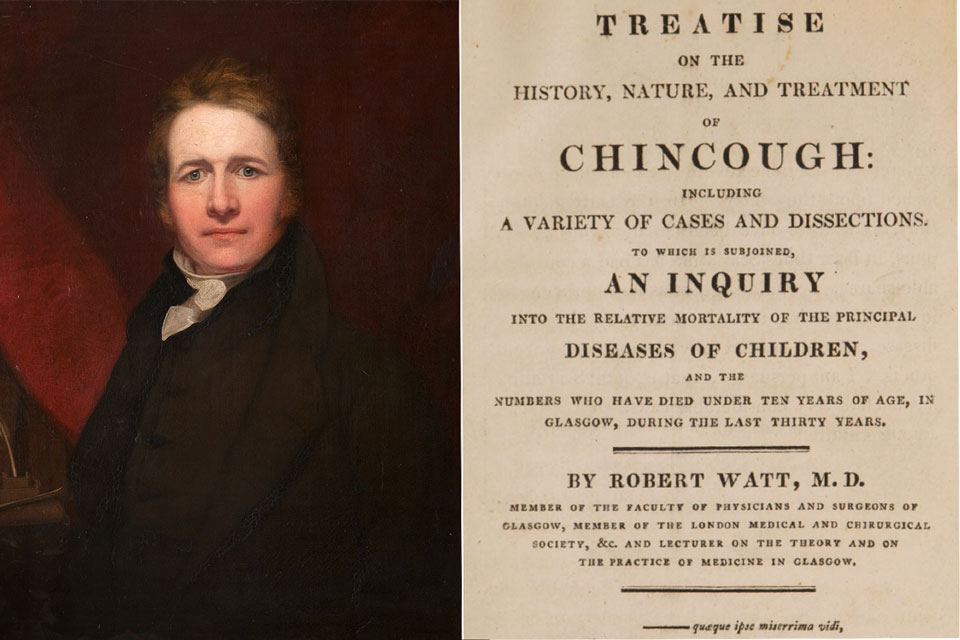

In mid-January 1813, the Glasgow physician Robert Watt asked a Mr Robert Limon, his pupil, for a terrible service.

He wanted Limon to dissect the recently-deceased Robert Watt jr, aged six, to gather clues to the “seat and nature” of the child’s final illness.

The diagnosis itself was in no doubt: pertussis (from Latin: per meaning “excessive,” and tussis meaning “cough”), also known as whooping cough or chincough, tends to announce itself.

Watt described its declarative symptoms:

“During the cough the expirations become extremely rapid and altogether involuntary. By the continuance of this process the air is suddenly expelled from the lungs, and the patient appears in danger of suffocation. At last he is relieved by a full and violent inspiration, generally accompanied with a stridulous noise, like the crowing of a cock, or the rapid passage of air through a narrow brazen tube.”

But giving the disease its proper name wasn’t the same as understanding what it did.

None of Watt’s therapeutic technologies – raising blisters on the chest, for instance, administering enema after enema, tapping five to six ounces of blood from the jugular, putting sinapisms on the ankles, giving draughts of laudanum-laced wine – had proven effective.

Instead, over the course of a couple of weeks, Watt had seen his son's coughing fits grow increasingly violent and “distressing"1, watched him lose weight, his face swelling; witnessed him snatching more and more desperately for air, until finally he stopped struggling for breath by stopping to breathe at all.

Watt had little time for grief. Three of his other children were sick with the same illness, and four-and-a-half-year-old Janet’s condition was in steep decline.

The day after her brother died, she was “so exceedingly low, that I had no hopes of her even seeing the morning,” her father wrote. Janet’s face was mottled, pale and livid; between “kinks” or fits of coughing she lapsed into a stupor. But she hung on, struggling, fading, rallying and failing, for another two weeks.

On January 30th, Mr Limon and his knife were called on again.

“A very general, and a very fatal disease”2

Watt blamed himself, but not exclusively himself, for his clinical helplessness in the face of his children’s illness.

Whooping cough remained “obscure and intractable” because the medical profession had “abandoned” it, he wrote.

Directly after his children died, he had set out to reverse that neglect, publishing a 400-page treatise on whooping cough that September.

Including notes from Robert and Janet’s dissections gave Watt cause to hope that he might claim “the consolation of thinking, that though his domestic losses have been severe, they have in some measure contributed to the public good.”

Properly demystifying pertussis had the potential to contribute in quantifiable measure to the public good, Watt knew. The sickness had been cited as the cause for 5-5.5% of all deaths – 10% of all deaths in children younger than 5 — in Glasgow over the preceding 30 years.

By 1812, smallpox, long the deadliest of childhood diseases, was being hobbled by vaccination, and now, as Watt sat writing, only measles counted as a more prolific killer of children in the city than whooping cough.

Echoes through time

Was it abandoned, or was it forgotten? Although 21st century molecular studies found that the two branches of the causative bacterium diverged from a common ancestor as long as 2000 years ago, still in the 1600s, European writers of medical texts were referring to pertussis as a “new disease”.

That said, no compelling evidence of whooping cough has been found in ancient texts. Historians have identified “possible allusions to pertussis” in literature from 7th century China, 14th century Korea and early 16th century India, and a disease recognisable as pertussis shows up in texts left behind by Persian physician Baha’al-Dawlah Razi, who died in 1508.

Between 1484 and 1495, two deadly epidemics of “an epidemic cough without catarrh” struck Herat, today in Afghanistan, at a few months’ interval. Al-Razi writes “the intensity of cough was to such an extent that it did not cease until vomiting occurred and weakness developed.”

Both adults and children fell sick and died, records Al-Razi, suggesting the possibility of an immune-naïve population – in other words, of an unfamiliar pathogen. In the second of the pair of outbreaks, death rates were lower.

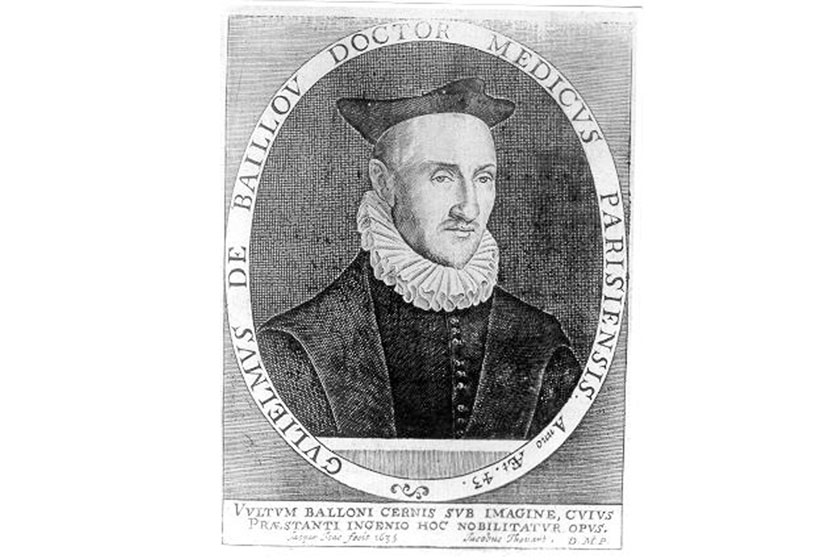

In 1501, whooping cough hit Rey, near Tehran, 1000 kilometers from Herat along the silk road. In 1578, French physician Guillaume de Baillou set down the first definitive description of the illness in Europe, after an epidemic of what he named “quintana” struck Paris in the late summer.

In any case, in 18th century Europe, pertussis seemed to be picking up pace. The Bills of Mortality from London show that in the 15 years to 1731, 632 deaths from “Chincough and cough” were recorded, citywide. In the following 15 years, that number rose to 1692; in the 15 years to 1776, it rose again to more than 4000. In Sweden a striking3 total of 43,393 children had died of pertussis in the 15 years to 1764.

Watt’s investigations, in other words, were not just urgent, they were overdue.

But they were also necessarily frustrated by the fact that he was writing almost half a century before Louis Pasteur published his germ theory of disease. The dissections got the Scottish doctor as far as establishing that whooping cough was an inflammatory – rather than a purely neurological or “spasmodic” – disease. He could find no remedy and no prophylactic: “in the treatment of Chincough, I have little or nothing new to propose,” he wrote.

It wasn’t until 1906 that the cause of whooping cough – a bacterium we now know as Bordetella pertussis – was isolated and identified. As soon as the bug was found, the hunt for a vaccine was on.

Meet the perpetrator: Bordetella pertussis

B. pertussis, a usually rod-shaped, but sometimes spherical or ovoid bacterium, is as difficult to pin down as you might expect from an invasive shape-shifter. Nearly 120 years after it was first isolated, we still don’t fully understand everything about how this bug makes us sick.

We know it’s spread principally via aerosolised droplets. It’s a human specialist, expert at clinging to the cilia -- tiny, hair-like extensions -– lining part of our upper respiratory systems. Once there, it begins to release several different toxins. Some of these suppress protective immune responses, while others damage tissue, paralysing the cilia and leading to a build-up of mucus. This, hampering the body’s ability to expel pathogens, which can increase the risk of pulmonary infection and pneumonia.

The most important of the pertussis toxins, from a disease perspective, is known (creatively enough) as pertussis toxin (PT). PT has a role in lots of damaging processes, including promoting lung inflammation, and causing heart issues, and eliciting a spike in the number of leukocytes – white-blood cells (specifically lymphocytes) – in the blood. When these build up in the small vessels of the lung of an infected child or infant, they can cause irreversible and deadly pulmonary hypertension.

Death can also follow complications caused by the cough itself, for example when the brain is starved of oxygen due to prolonged, violent coughing fits. What actually causes the cough has long been an unresolved question: as recently as 2015, pertussis expert James D. Cherry wrote, “In contrast with PT, nothing is known about the cough toxin.” The research has moved on in years since – but not to the point of concrete resolution.

Frustrating immunological beginnings

It took scientists Jules Bordet and Octave Gengou six years of work in their Brussels lab to isolate and culture the microbe they had first spotted in the sputum of Bordet’s infected baby daughter in the year 1900.

It took another three years to discern the presence of the exotoxin – later called pertussis toxin (PT), in fact one one of several active proteins produced by the bacterium Bordetella pertussis – that is understood to be directly responsible for many of the disease’s symptoms.

The flag was up: as soon as 1912, Gengou announced the world’s first pertussis vaccine. In 1913, Charles Nicolle of France was working on a sequence of pertussis vaccines, and by 1914, no fewer than six pertussis vaccine products were licensed in the USA.

But these vaccines failed to produce consistent results, and by 1931, the Council on Pharmacy and Chemistry of the American Medical Association had withdrawn its approval from all commercially produced pertussis vaccines.

In 1925, Danish scientist Thorvald Madsen became the first to describe the roll-out of a pertussis vaccine at scale, after he deployed his candidate to control two outbreaks in the Faroe Islands. His vaccine showed “some protection”- mitigating disease severity, and moderating incidence. It also appeared to be unsafe: two children had died within a day of its administration.

Have you read?

Through the 1930s and into the 1940s, signals of frustration cropped up here and there in the scientific literature. “Despite the efforts of the clinician and the immunologist, whooping-cough is still with us,” lamented a 1933 article in the British Medical Journal, calling it “puzzling” that “killed suspensions of the Borden microbe failed to provide dependable protection.”

Between 1921 and 1930, 44,000 deaths had been precipitated by pertussis in England and Wales – about 1% of the total mortality of the population. In the USA, meantime, 36,013 deaths from pertussis had been logged between just 1926 and 1930.

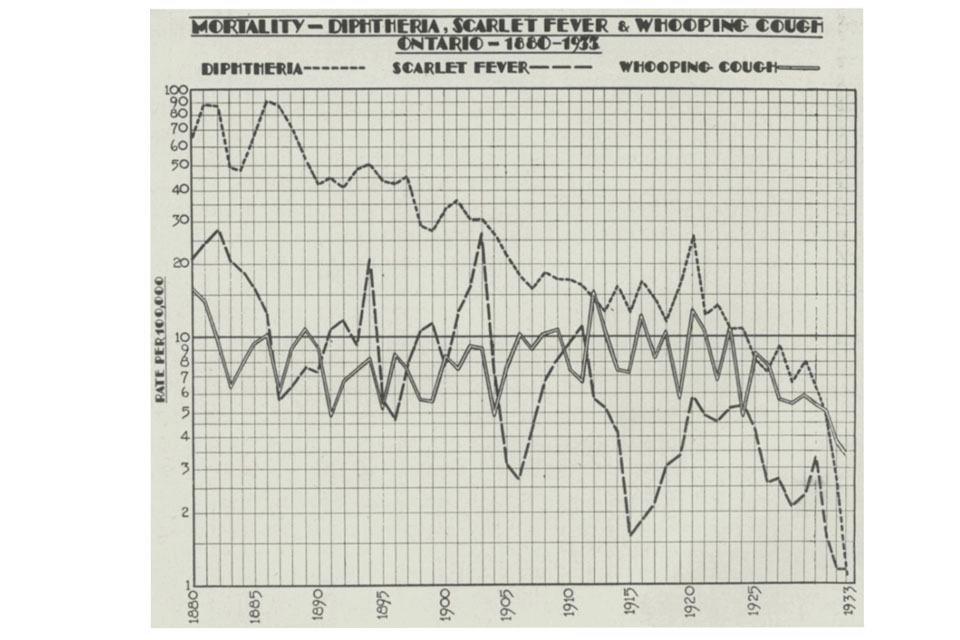

In Toronto alone, about 4,000 cases a year were the average, with “no certain evidence of any sustained decline,” in for the half century to 1933 in Ontario, according to a 1934 analysis published in the Canadian Public Health Journal.

Significantly, these researchers found that whooping cough mortality had “maintained,” even as deaths from diphtheria – another toxin-mediated illness for which a toxoid vaccine had been discovered in 1923 – had plunged.

Towards a working vaccine

But in Grand Rapids, Michigan, relief was brewing.

Even in retrospect, the circumstances that would produce this next great breakthrough in pertussis control look unpromising. It’s 1932 – year three of the Great Depression. In a “dumpy, broken-down stucco” building in a town rapidly going broke, two women labour after-hours in a scantily-funded lab.

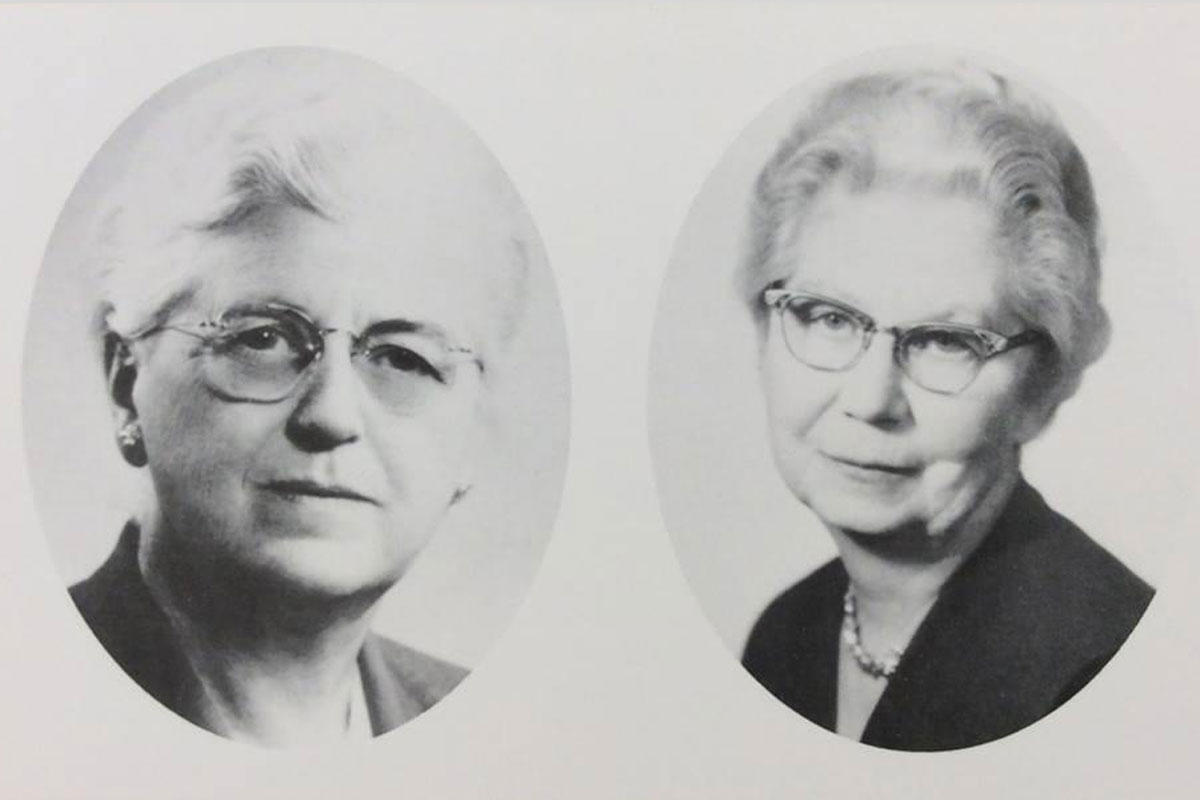

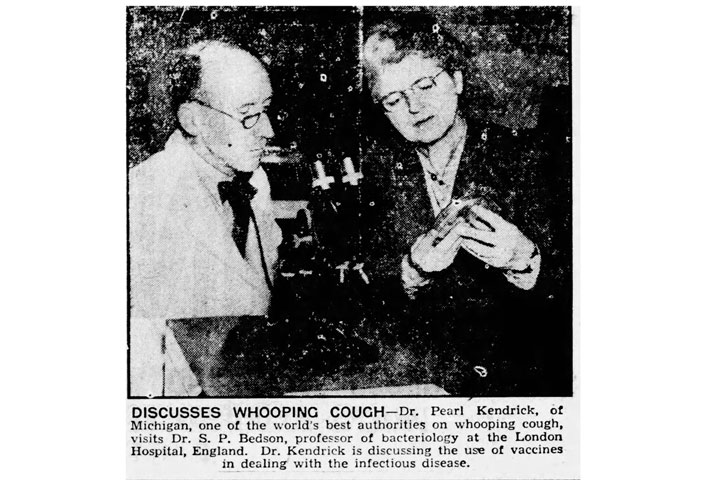

They were bacteriologists Pearl Kendrick and Grace Eldering4 , employees of the Western Michigan Branch of the State Laboratory, positions that anointed them to such thrilling responsibilities as the regular, routine analysis of the local milk and water supply.

But the Michigan Department of Health had a reputation for being more ambitious than many of its contemporary equivalents. In the 1920s it was among the few that funded work on biologics – diphtheria vaccine and antitoxin, for instance.

The Bureau of Laboratories offered incentives to employees to stay on the scientific cutting edge, and when he offered Kendrick a job in 1920, Director Cy Young had told her, “I am sure that we can make it interesting for you.”

Then came the Depression. Money was short and public health exigencies – fuelled by poverty – grew sharper. In 1930, the Department called a halt to all research work.

A year later the statewide laboratory workload was reshuffled, with some of the more workaday analysis shunted onto city labs, to wedge open the opportunity for a return to work on biologics.

In 1932, Kendrick – who had been recently named Associate Director of Laboratories and hired Eldering – took that slender chance and wrote to her boss for permission to begin research on pertussis. His tepid endorsement5 made it clear the investigations would need to happen on the scientists’ own time.

So began years of evenings. “When the work day was over, we started on the research because it was fun,” Eldering remembered in 1984. “We’d come home, feed the dogs, get some dinner and get back to what was interesting.”

Much of the work was not at the lab-bench but out in the community, collecting thousands of diagnostic cough-plates – agar plates onto which symptomatic children coughed their sputum, an on which the bacillus could then be isolated and cultured.

These efforts produced some important epidemiological discoveries – for instance, that the duration of the infectious period in whooping cough was in fact longer than the previously-established quarantine guidelines.

They also brought the scientists face-to-face with the human reality of unchecked pertussis. “We listened to stories told by desperate fathers who could find no work. We collected specimens by the light of kerosene lamps, from whooping, vomiting, strangling children. We saw what the disease could do,” said Eldering later.

How Kendrick and Eldering vaccinated America

Like other scientists working on pertussis vaccines, Kendrick and Eldering were experimenting with different means of producing a vaccine that was made of killed6, and therefore non-infectious, whole Bordetella bacteria.

They built on Madsen’s work, and were in contact with contemporaries, like paediatrician Louis W Sauer, who was working towards his own candidate vaccine in Illinois.

Certainly, the vaccine had to work, and it had to be safe. But to make any difference at scale, it also needed to be affordable enough and easy enough to reproduce reliably.

Unlike many of their colleagues and forerunners in the pertussis field, Kendrick and Eldering meticulously systematised the steps to production, testing iterations of their vaccine on animals and on themselves before they were ready to test it on children.

By 1934, their vaccine was ready for a first field trial. 1600 children took part. “I felt scared to death most of the time,” Kendrick said, recalling a period of sleepless nights. But the dreaded news of a bad reaction to the jab never came. Instead, in 1936, there was good news: while 4 of the 712 vaccinated children had suffered mild bouts of whooping cough, 45 out of the 880 “control” children had battled full-blown pertussis.

But the scientific community had been burnt: so many promising pertussis vaccine candidates had flunked in trials that this encouraging result was met with scepticism.

The APHA subcommittee on whooping cough – which included Kendrick and Eldering – drafted in epidemiologist Wade Hampton Frost to review the trial. He found weaknesses in the trial’s design, but even with these factored in, he conceded that the results seemed to stand. “Your data when finally analyzed are likely to show some protection in the vaccinated group,” he wrote to them, recommending two further trials.

But now funding – scratched together from a ragtag diversity of sources for the first few years of the project – was easier to attract. So were volunteer trial participants. By 1939, more than 4000 children had received the Kendrick-Eldering vaccine. By 1940, it was being distributed across the country.

The evidence for the vaccine accrued quickly, to undeniable scale. By 1948, the national death rate from whooping cough had plummeted to less than 1 per 100,000 people, from 5.9 per 100,000 in 1934. After 1960, fewer than 10 Americans in every 100,000 even got sick with pertussis each year.

By 1970, vaccination against whooping cough in the USA had reduced the incidence of the illness 157-fold, against a pre-vaccine baseline. In the 1980s, a total of about 9 deaths from whooping cough were reported each year.

A backlash brews

The sound of the cock-crow paroxysmic whoop was fading from the cultural memory.7

And then, tragically, the graph-line began to bend the wrong way. “A lot of mothers who come in here are really nervous about the vaccine,” nurse Gloria Murray-DeBiasi told the New York Times in 1986. Unvaccinated children began to turn up blue and breathless in hospital wards.

What happened then? Read about the backlash against the pertussis vaccine in our next Tale from the Past.

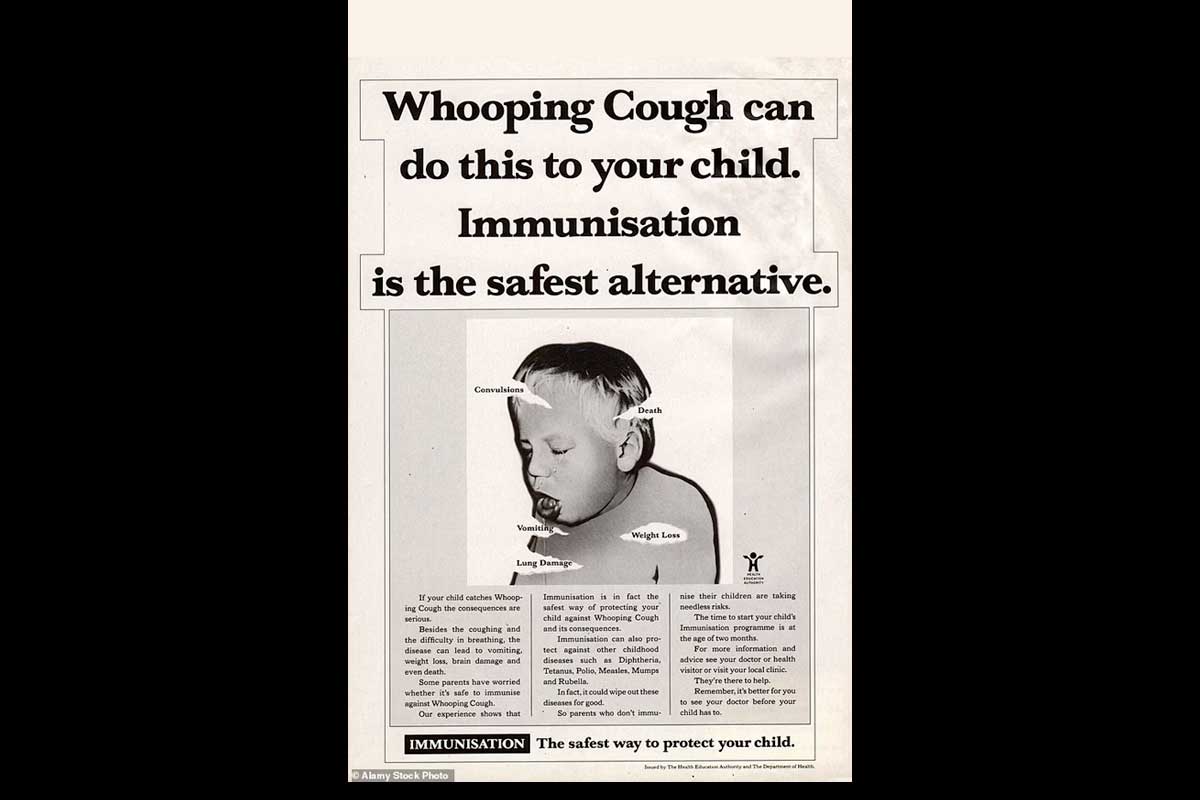

1 During violent coughing paroxysms, patients of Watt’s, including his son, experienced extreme effects, vomiting, suffering anal prolapse, or fainting and slipping into convulsions. In modern times, we know that oxygen deprivation during pertussis-induced coughing fits can damage the lungs long-term and result in brain injury.

3 Robert Weston suggests Sweden’s whooping cough incidence - he borrows from Von Rosenstein an average figure of 2,712 paediatric deaths per year for the same period - may have been “exceptionally high” for the period

4 Though gender was no doubt a barrier both women had to hurdle to win success in science, in a weirdly regressive way, it was also an enabler. Women were generally cheaper to hire than their male counterparts, so as public budget shrank in the Great Depression, the number of women awarded especially entry-level roles in public health rose.

5 A year later, when she wrote again for permission to expand their scope of work, Young wrote back, “Go ahead and do all you can with pertussis if it amuses you.”

6 In Kendrick and Eldering’s case, the killing agent was a common antiseptic

7 “Many 1980s parents are simply not familiar with the disease. “They may have heard of whooping cough in the “olden deys,” but a lot of them don’t relate to it as a reality now,” said a nurse with the Waterford public health nursing service, Nancy Clark.” NYT, Oct 26 1986

More from Maya Prabhu

Recommended for you