Man versus mycelium: The race to create vaccines against fungal threats

A vaccine that protects dogs against fatal fungal infections is set to launch in 2024. As more fungi become resistant to treatment, could urgently needed human vaccines follow?

- 3 July 2023

- 11 min read

- by Linda Geddes

In early 2009, a 74-year-old man was admitted to Ajou University Hospital in Suwon, South Korea with what turned out to be laryngeal cancer. After undergoing surgery to remove his voice box, he developed a lung infection, during which he started bleeding from his lower intestine.

Antibiotics didn't clear the infection, and further tests showed he had a bloodstream infection caused by Candida auris – a yeast that was discovered for the first time when it had recently been detected in the ear of a 70-year-old woman in Tokyo. Now, here it was again, and existing antifungal drugs were unable to stamp out the infection; 79 days after arriving at hospital, the man died from septic shock and multiple-organ failure.

“Emerging from the shadows of the bacterial antimicrobial resistance pandemic, fungal infections are growing, and are ever more resistant to treatments, becoming a public health concern worldwide."

– Dr Hanan Balkhy, WHO Assistant Director-General of Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR)

In the 14 years since then, C. auris has spread to more than 30 countries on every continent except Antarctica, triggering hospital outbreaks in high- and low-income countries alike. The emergence of this pathogen, seemingly from out of nowhere, has added to a mounting sense of concern amongst infectious disease researchers. While drug-resistant bacterial infections such as MRSA or XDR-TB make headlines regularly, resistant fungal infections are rarely talked about – even though they are increasingly become a public health threat.

Fungal infections already infect 13.5 million and kill about two million people each year (mostly in the Global South) – more deaths than either TB or malaria – and this toll is growing as the number of susceptible individuals around the world increases.

Pathogenic fungi are also becoming increasingly resistant to the small number of anti-fungal treatments available, with very few alternatives in the pipeline, and there are currently no vaccines to prevent fungal infections in people.

Nevertheless, a few laboratories around the world have had recent breakthroughs, fuelling optimism that vaccines against multiple types of pathogenic fungi might be achievable. A Californian company called Anivive is even on the verge of launching one: a vaccine designed to protect dogs against the Coccidioides fungus that causes Valley Fever. Assuming their vaccine is approved, it would represent a major milestone in the multi-millennia battle of man versus mycelium. "This will be the first systemic fungal vaccine in history for humans or animals," said Dylan Balsz, Anivive's CEO.

Graphic by Anivive Lifesciences, Inc.

Even so, creating a vaccine that could protect people against not just today's major fungal killers, but also against emerging ones, remains a massive challenge.

Fungal world

Although only a fraction of the estimated 12 million fungal species that exist can infect humans, fungal pathogens are becoming increasingly common and resistant to antifungal treatments. Tests to quickly and accurately diagnose infections are also not widely available or affordable in many countries, while the geographic range of certain fungal diseases – including Valley Fever – are expanding due to global warming and increased international travel and trade.

In 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) released its first-ever fungal "priority pathogens" list – a global initiative to galvanise efforts to combat species presenting the greatest threat to human health. The report called for increased surveillance and antifungal development, plus better diagnostic tools to ensure patients are quickly treated with appropriate drugs.

"Emerging from the shadows of the bacterial antimicrobial resistance pandemic, fungal infections are growing, and are ever more resistant to treatments, becoming a public health concern worldwide" said Dr Hanan Balkhy, WHO Assistant Director-General of Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR).

So, what about vaccines? These are among the most powerful and cost-effective interventions against other infectious agents, so developing vaccines against deadly fungi may seem like a no-brainer.

Yet, fungi are more biologically complex than viruses and bacteria. Vaccines work by showing our immune systems an antigen – a part of the pathogen that can trigger an immune response – and our bodies respond more strongly to some antigens than others.

"Fungi can be a hard nut to crack because they have such a such a thick cell wall, and so it can be hard to crack through the armour and get at fungal antigens," says Bruce Klein, a professor of paediatrics, medicine, and medical microbiology and immunology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, US. "Their genomes are also gargantuanly bigger than viruses, so there are far more antigenic targets to sift through."

Further complicating matters, many fungi change shape once they've entered the body. Infections typically start after we inhale the spores of a fungus, but if the immune system fails to destroy them at this stage, the fungus changes into a different cell type, making it difficult for the immune system to target.

However, the challenges aren't only scientific, Despite WHO stating that fungal pathogens are a priority, "in terms of political or scientific will, I don't know that this is a topic that has been prioritised, and funding matters," says Klein. "You can do all the work to create a fungal vaccine, but if there's no one to commercially take the baton and carry it forward, it will die on the vine."

Valley Fever

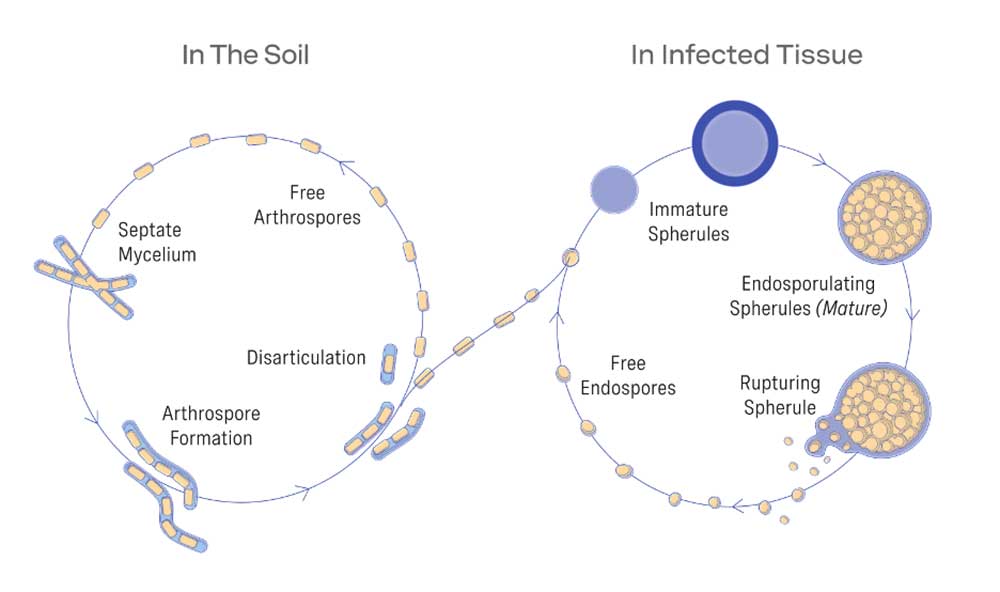

Yet there is some hope, as a few companies have invested the legwork in developing vaccines. Anivive's decision to create a vaccine against Valley Fever initially sprang from local need. In the Southwestern US, Mexico and parts of central and South America, Coccidioides – which causes Valley Fever – is a significant health problem in dog and man, and its range is increasing because of climate change. The fungus lives in dust and soil, but its spores can become airborne if contaminated ground is disturbed by humans, animals or the weather. Once inside the lungs, the spores begin to grow into structures called spherules, which eventually break open and release further endospores that then spread within the lungs or to other organs.

Graphic by Anivive Lifesciences, Inc

More than half of human infections are asymptomatic, but the fungus can cause symptoms such as coughing, breathing difficulties and fever, and approximately 1-2% of people will develop complications that can result in the need for lifelong antifungal treatment, permanent disability or death. Dogs are even more susceptible to such complications, and the cost of medical care sometimes leads to their being euthanised or abandoned.

Anivive's vaccine was borne from research on a related fungus that affects maize (corn) crops. Scientists discovered that if they deleted a gene called CPS1, the fungus found it harder to establish an infection in these plants. When they deleted the same gene in Coccidioides and exposed mice to its spores, they found that they no longer became sick, and were highly resistant to subsequent respiratory infection with naturally occurring Coccidioides fungus.

Subsequent experiments in dogs suggested that vaccinating them with spores from this genetically modified fungus also protected them against disease. "In all the groups that got a prime and a booster shot, the vaccine was 100% effective at preventing clinical symptoms," Balsz said.

Have you read?

The company is currently awaiting the results of a final safety study in pet dogs, before submitting its data to the US Department of Agriculture. Balsz is hopeful that their vaccine could be approved during the first half of 2024. They are also planning to test it against two other fungal infections that affect dogs and humans: blastomycosis, a rare but serious lung infection caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, and histoplasmosis, caused by histoplasma, as their genetic sequences are quite similar. These experiments are expected to be completed by autumn.

Mechanistically, Balsz sees no reason why this approach wouldn't similarly protect humans against Valley Fever, and they are looking to advance it towards human trials with support from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Alternative approach

This isn't the only approach being explored, though. Even before the discovery that deleting the CPS1 gene rendered Coccidioides harmless, Klein and his colleagues had been studying how the immune system responds to Blastomyces dermatitidis and trying to develop a vaccine against it. They discovered that deleting a gene called BAD-1 resulted in a strain that could be used to safely immunise mice and dogs against it.

Since then, they have identified at least one key part of the fungus that the animals' immune systems are responding to – a protein called calnexin, which is present on the cell walls of many fungi. They have also discovered that the sequence of this antigen is highly conserved (i.e. similar) between even distantly related fungal species – including Pseudogymnoascus destructans, a fungus that is currently decimating hibernating bat populations across North America.

A vaccine incorporating the calnexin antigen is currently being tested in wild bats in Wisconsin and other US states, and is showing "considerable promise", Klein says: "It doesn't completely protect against infection, but it protects against severe disease, and reduces the extent of the infection."

Klein has also tested the antigen against Coccidioides and Histoplasma, with published evidence to indicate that it triggers a protective response to them too. "As proof of concept, one could call it a pan-fungal vaccine – but it's not perfect," Klein says. "So, I think it's likely we would need to incorporate more than one antigen."

Fungal killers

What about major human pathogens such as aspergillus, candida or pneumocystis? Together, these fungi account for roughly 40% of the estimated 13.5 million people who are affected by fungal infections worldwide each year. They are also responsible for about 55% of the annual 1.6 million fungal disease deaths – the majority of which occur in the Global South.

“The real breakthrough for this type of a vaccine is that it targets several different pathogens that patient populations are susceptible to”

– Karen Norris, professor of immunology at the University of Georgia

Karen Norris, a professor of immunology at the University of Georgia, has been developing a vaccine that may protect against these groups of fungi, and potentially others. It is based on a fragment of a protein called kexin, which is also found on the surface of many fungal pathogens. In late 2022, Norris' group published preclinical data suggesting that their vaccine candidate protected mice and non-human primates against serious disease caused by various species of aspergillus, candida and pneumocystis, including Candida albicans, an opportunistic yeast that is a common cause of bloodstream infections among hospitalised patients.

"The real breakthrough for this type of a vaccine is that it targets several different pathogens that patient populations are susceptible to," says Norris.

This may even extend to Candida auris. "The vaccine induces antibodies that cross-react with Candida auris, so we're exploring whether it's also protective," Norris says.

Weak immunity

However, identifying antigens that will provoke an immune response against deadly fungi is only part of the challenge. Whereas Valley Fever, blastomycosis and histoplasmosis often strike down healthy people, major killers such as aspergillus and pneumocystis predominantly affect people with weakened immune systems, such as organ transplant recipients, people undergoing chemotherapy for cancer or HIV/AIDS patients.

"The question is, how do you stimulate immunity in somebody that doesn't have any immunity?" Klein says.

One strategy would be to vaccinate people in advance of medical procedures such as cancer surgery, so that they still have some protective antibodies circulating in their blood, even after their immunity takes a dive. Norris points out that people with asthma, diabetes and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are also at greater risk of infections with aspergillus, for instance, and may benefit from a prophylactic vaccine.

Another potential strategy could be injecting patients with immune cells that have been engineered to fight specific fungal pathogens. For instance, researchers led by Jürgen Löffler at the University of Würzburg in Germany recently reported creating chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells against Aspergillus fumigatus, one of the most common causes of disease in immunosuppressed individuals, which helped to clear aspergillus infections in mice. This approach, known as adoptive cell therapy, is already being used to treat certain types of cancer – although it is expensive and may be difficult to implement in developing countries.

Vaccinating against candida presents a slightly different challenge. These yeasts commonly dwell on the skin and in the guts of healthy individuals and removing them may have negative consequences, as it's not clear what organism may take its place to colonise our guts instead. Also, most people acquire these fungicide resistant organisms in the hospital setting. "It would be difficult to know when to vaccinate those at risk far enough in advance to mount an immune response before they see the resistant organisms and become colonised," says Anivive's Chief Medical Officer, Dr David Bruyette. "Vaccines may not be the best approach."

Even if vaccination proves effective, bringing these products to market presents additional difficulties, as Anivive has discovered. First, there's choosing the right ingredients to keep the vaccine stable during transportation and storage. Usually, developers would look to existing vaccine formulations and processing methods for clues about the best approach, but for fungal vaccines there were no precedents, and methods that worked for bacterial and viral vaccines were often too harsh on the fungal spores. "We went through about 80 different versions before we identified what would work," Balsz says.

Finding a manufacturer willing to work with them was also difficult because, even though the strain of Coccidioides they needed to grow was harmless, "you don't want it on equipment that's used for other items or products," Balsz says.

Eventually they found a manufacturer, and the production facilities are now in place to ramp up production of their vaccine, assuming the US Department of Agriculture gives it the green light. If it does, this vaccine will go down in history as the first to strike a blow against a fungal killer.

Others may follow, although the path to creating human vaccines will undoubtedly be more complex. Also sorely needed are new classes of antifungal drugs to replace those that fungi are increasingly developing resistance to.

Candida auris is a reminder that new fungal pathogens can arise, seemingly from out of the blue. Defeating them requires the world to wake up to the risks posed by fungi, and to invest in research to better understand these organisms and how they interact with us. Fungi are among the oldest and most populous life forms on the planet. We underestimate them at our peril.