A new gene therapy could revolutionize the treatment of diseases like sickle cell anaemia. Here’s how

The UK is the first to approve a CRISPR-based gene therapy for treating sickle cell disease and beta thalassemia. But not everyone is likely to get access.

- 6 December 2023

- 5 min read

- by World Economic Forum

The world's first treatment based on gene editing technology has been approved by the UK's medicine regulator, potentially revolutionizing the treatment of two debilitating blood disorders.

The therapy, called Casgevy, has been approved for use to treat sickle cell anaemia and beta thalassemia, inherited, lifelong conditions that can be fatal. It is based on CRISPR technology, which is able to precisely edit DNA mutations within affected patients, potentially leading to permanent results.

Sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia are caused by faults in the genes that encode haemoglobin, which is crucial to red blood cells' ability to transport oxygen around the body. This can result in pain, a number of health complications and a lifetime of treatment and blood transfusions. What's more, people with sickle cell disease are estimated to lose around $700,000 over the course of their lifetime because of their inability to work.

To date, the only lifelong way of treating these diseases was through a bone marrow transplant, a process which comes with its own complications as the bone marrow must be from a closely matched donor and, even then, it may be rejected.

Experts hope that the new treatment will be transformative, as a single treatment may lead to permanent changes.

What is gene therapy and how does it work?

Casgevy is the first treatment to be licensed using CRISPR technology, which works like an incredibly precise pair of genetic scissors. These scissors allow for the editing of DNA, enabling scientists to make changes to genomes over the course of a few weeks. Although gene editing was possible before CRISPR, it took years, was very costly and lacked the specificity and precision to target desired sequences.

CRISPR, pronounced 'crisper', trips off the tongue more easily than the Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats it stands for. These repeats form part of a bacterial defence system which works by cleaving the DNA of invading viruses. They were discovered by accident in 2011, and it was subsequently shown they could be reprogrammed to cut any DNA molecule at any location. The scientists who made this discovery – Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna – went on to win a Nobel prize for their work.

Casgevy is designed to edit DNA taken from a patient's bone marrow so that they are able to produce functioning haemoglobin. Treatment involves bone marrow being extracted from a patient, and then being treated in a laboratory. The treated cells are then infused back into the patient, who may need to spend up to a month in hospital while the treated cells become established and start to produce stable haemoglobin.

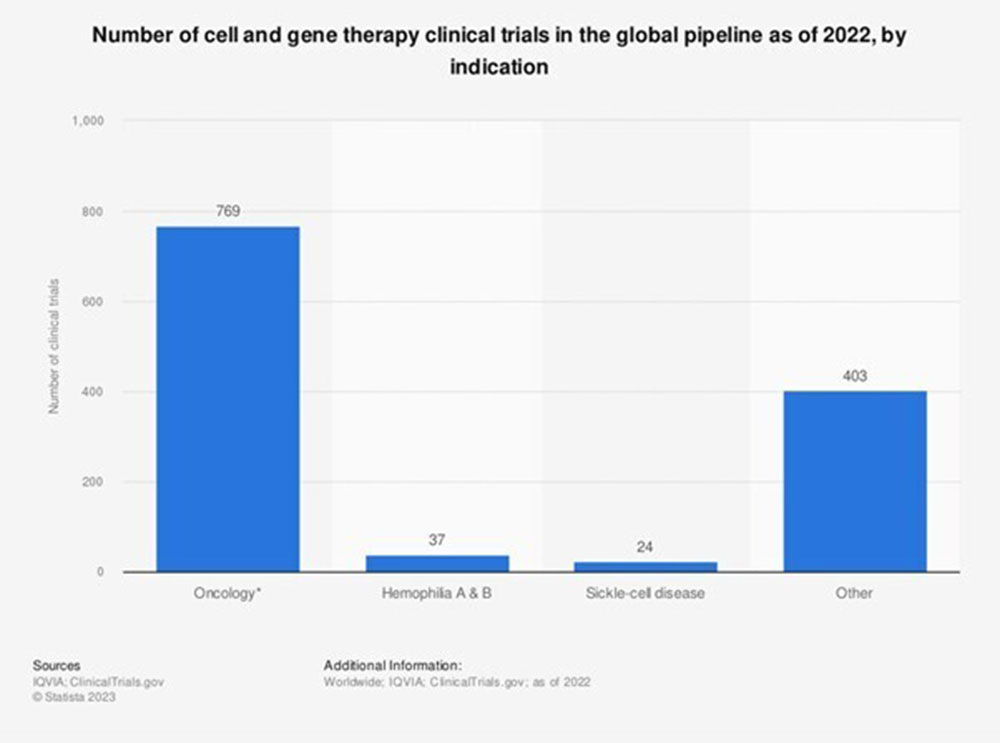

Image: Statista

What are the effects of the treatment?

People with sickle cell disease can have episodes of severe pain, called sickle cell crises, which can last for weeks. They are also at increased risk of life-threatening infections and may become anaemic, where their bloods' inability to transport sufficient oxygen leaves them tired and short of breath. They may require regular blood transfusions to treat the condition. The disease is particularly common in people with an African or Caribbean family background.

People with β-thalassemia may also become severely anaemic, and often need a blood transfusion every 3-5 weeks. The condition mainly affects people of Mediterranean, south Asian, southeast Asian and Middle Eastern origin.

Have you read?

Based on trial data, 28 of 29 sickle cell patients who have taken Casgevy long enough to be analyzed were free of severe pain for at least a year after treatment. And 39 of 42 β-thalassemia patients did not need a red blood cell transfusion for at least 12 months following treatment. The three remaining patients had a 70% reduction in the need for red cell transfusions.

The trials are ongoing and it is hoped that the results seen will be permanent.

Who will benefit?

So far the treatment has only been approved for use in the UK, and it is currently being reviewed by other medicines agencies. However, the treatment is extremely costly and not one that could easily be administered in many low-to-middle-income countries.

The cost of the treatment has been estimated at $2 million per patient, according to Nature.

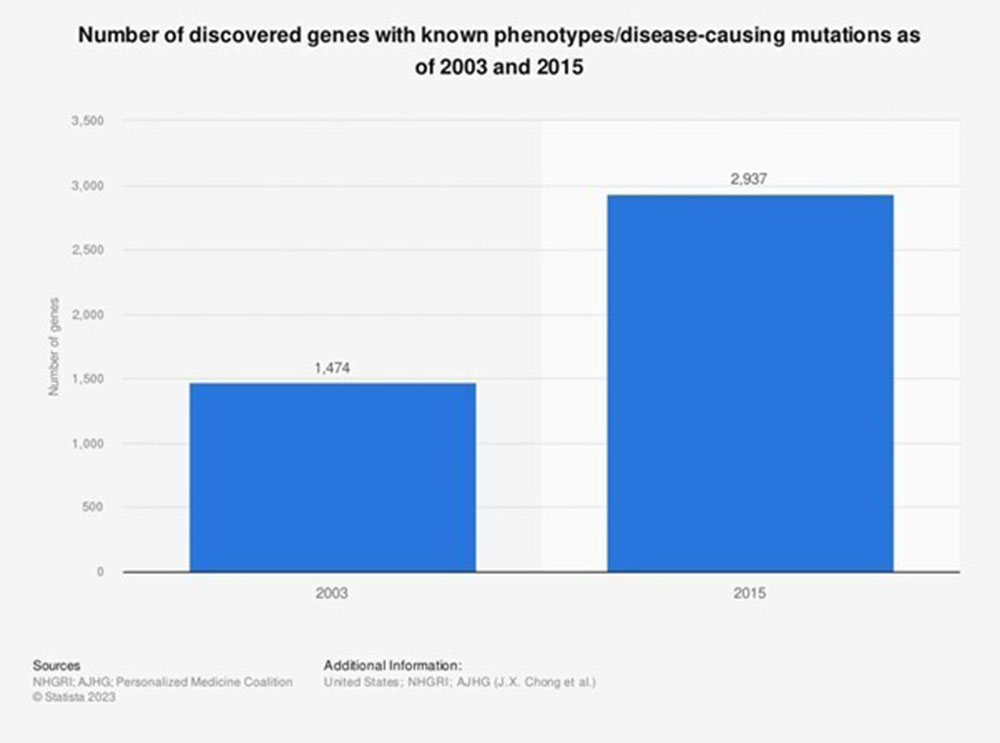

Image: Statista

What next?

Many genetic conditions such as sickle cell, thalassemia or cystic fibrosis are caused by a single mutation or error in one of the roughly 3 billion base pairs that make up the human genome.

Gene therapy is a promising and rapidly moving new form of treatment which offers potential to revolutionize treatment for a whole host of conditions. In the future it may have applications to treat or prevent everything from high cholesterol to cancer. The technology could also help fight diseases indirectly, for example by addressing the spread of mosquito-borne diseases such as malaria.

The CRISPR gene market is expected to grow from around $2.4 billion in 2023 to nearly $33 billion within a decade.

The future of medicine is likely to be increasingly personalized. And as the World Economic Forum's Global Health and Healthcare Strategic Outlook discusses, along with expanding and ageing populations relying on more and better healthcare, systems face rising costs and increasing pressure. The report offers a vision for 2035 with steps governments and health bodies can take to better meet the challenges future healthcare systems will face.

Written by

Charlotte Edmond, Senior Writer, Forum Agenda

Website

This article was originally published by the World Economic Forum on 30 November 2023.