The pernicious infections infiltrating Ukraine’s front lines

Doctors and scientists are waging a shadow war in the besieged nation: bacteria that are resistant to multiple antibiotics. The deadly bugs are now knocking on western Europe’s door.

- 8 October 2025

- 18 min read

- by Knowable magazine

Reporting for this story was supported by the Pulitzer Center

As Hailie Uren rushed to meet the injured British soldier evacuated to her hospital in western Ukraine, the Australian clinician reflected on how vulnerable the young man must feel, speaking no Ukrainian. When she got to his bedside, he blurted out, “Oh my God, thank God!” Then he quickly asked her: “Am I going to lose my leg?”

A few weeks later, on a sunny June afternoon in Lviv, the 24-year-old soldier with black curly hair and beard and intense dark eyes is lying in the room he shares with three other men with war injuries at the city’s St. Panteleimon Hospital. He grew up in South London, he explains, and had worked in private security before joining Ukraine’s International Legionnaires in January 2025. “I came here for a higher purpose,” he says — “stopping evil before it spreads further into Europe.”

After training, he was deployed to the eastern Kharkiv region to repulse Russian advances. One day in April, picking his way across a minefield, he was hit by shrapnel from a mortar that had exploded a few feet away. He tried to get up, he says, “but I could feel bones crunching in my hip.” He buckled, and a comrade dragged him to safety.

Military doctors had warned him in broken English that if the bacteria that invaded his shattered pelvis resisted antibiotics, he could lose his leg. “It would have been an extremely high amputation,” says Uren.

His prognosis hung on the results of a lab report that would unmask his pathogens.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, now deep into its fourth year, has taken a ghastly toll. Tens of thousands of soldiers and nearly 14,000 civilians in Ukraine have succumbed to often grisly injuries from shelling, drone explosions and missile attacks. Survivors must contend with another, invisible threat: bacteria that are resistant to multiple antibiotics.

A rising number of wounded soldiers are infected with such strains, which include some microbes that are extensively drug-resistant or even pandrug resistant — they withstand most or all antibiotics thrown at them. “The mortality rate in Ukraine far exceeds what you see internationally,” says Uren, who until August led the charge against antimicrobial resistance in Lviv. “And that’s really frightening.”

The public health nightmare would be bad enough if it were confined to Ukraine. But globally, antimicrobial resistance is a bigger killer than HIV or malaria; in 2021, it was the direct cause of an estimated 1.14 million deaths worldwide, according to a 2024 report in The Lancet. The authors of that report predicted a total of 39.1 million deaths attributed to antimicrobial resistance over the next 25 years.

The worst of these drug-resistant strains “no longer respond to some of the most powerful antibiotics available,” says Luise Martin, a pediatrician and infectious disease specialist at Charité University Hospital in Berlin who helps to manage antimicrobial stewardship at the facility. And the invasion of Ukraine stands to add fuel to the fire.

Aided by European allies and the United States, Ukrainian health authorities are trying to tackle what appears to be the root cause of the multidrug resistance: a breakdown in infection control and prevention in overwhelmed casualty wards. Exacerbating that is a longstanding misguided practice by some doctors at trauma units of conserving supplies by prescribing low doses of antibiotics.

With efforts to contain the antimicrobial resistance threat in Ukraine falling short, dangerous drug-resistant strains have begun circulating in the general population, including among young children and people with mild symptoms. “It’s definitely not confined now to the war-wounded,” Uren says, nor to other patients who pick up resistant bugs in hospitals. The Lviv region in which she works has some of the highest multidrug resistance levels in all of Ukraine, she says: both within hospital walls and beyond, showing up at clinics and doctor’s offices all over the city. And Lviv is just 70 kilometers from the border with Poland and the European Union.

“Right on their doorstep,” Uren says.

Managing chaos

The antimicrobial resistance situation in Lviv may be dire, but Uren, who often flashes a radiant smile, is relentlessly upbeat. She cut her public health teeth during the pandemic in Brisbane, work that included leading the city’s Covid-19 vaccine rollout in 2021. “That was my first foray into this world,” she says. “It was exhilarating.” Early in 2022, she took a course on disaster and emergency medicine in Italy, where she met the head of UK-Med, a British charity. He offered her a job in Dnipro, an industrial city around 400 kilometers southeast of Kyiv. “I knew nothing about Ukraine,” says Uren, who imagined that the whole country was a war zone.

After settling in Dnipro that December, Uren was on the road often to UK-Med’s mobile clinics around the country, ensuring that health care providers had the right medicines. “They would talk about how horrific the infections were,” she says — a challenge that intrigued her. “It sounded like something that would make better use of my skills.”

In early 2023, officials at the First Lviv Territorial Medical Union asked UK-Med if the charity could connect them with someone who could help the more than 2,400-bed complex, which includes St. Panteleimon Hospital, manage how antibiotics are prescribed. Uren leapt at the opportunity, taking a full-time position with the medical union that November.

To Uren’s dismay, the hospital complex had not been keeping systematic records of infections in its patients, thousands of whom have been soldiers sent there for reconstructive surgery or burn treatments. By the time they arrive in Lviv, they may have spent days or weeks in several trauma units or hospital wards. “We don’t know their full history, which hospitals they’ve been through,” Uren says. She and clinical pharmacist Nataliia Aliieva painstakingly compiled handwritten notes on patients from the hospital complex’s microbiology lab and its archive. “I learned very quickly how to read Cyrillic,” Uren says.

After analyzing more than 6,800 diagnostic isolates, Uren and her colleagues made a grim discovery. When doctors prescribe antibiotics without knowing for certain which bacteria they are treating, 80 percent of the likely culprits should still be susceptible to the drug. Yet, for some antibiotics, they were finding 30 percent or less. “That’s quite scary,” Uren says. “It means they will work in only about 30 percent of patients.”

Their report in the Lancet Infectious Diseases in April 2025 keyed in on a trio of genera already on the global antimicrobial resistance radar: Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter and Klebsiella. All three are gram-negative bacteria, which have a characteristic cell wall that helps to protect against enzymes, detergents — and antibiotics. All three are notorious for colonizing burns and traumatic wounds, toeholds from which the battlefield scourges can slip into the bloodstream and cause life-threatening sepsis.

There was ample reason to worry that Ukraine, like other conflict zones, would turn into a crucible of drug resistance. During the Iraq War in the early 2000s, military hospitals were so riddled with drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii that doctors nicknamed the rod-shaped organism “Iraqibacter.” The pathogen appears especially adept at forming biofilms, allowing it to persist on hospital surfaces longer than most other pathogens, infecting new critically wounded.

“It can also go through the air. It’s very difficult to ever get rid of it,” says Heiman Wertheim, a medical microbiologist at Radboud University Medical Center in the Netherlands who has spent time in Dnipro and Lviv helping colleagues tackle multidrug-resistant microbes. Twenty years ago, A. baumannii strains were generally sensitive to carbapenems, a class of wide-spectrum antibiotics. Not anymore: Many A. baumannii now possess the genetic machinery to resist those drugs.

As Iraqibacter rose to notoriety, Ukraine, like other former Soviet nations, was taking a laissez-faire approach to antibiotic usage. Many antibiotics were available at pharmacies without a prescription. “If your kid had a fever, you’d give him an antibiotic, even though it was almost surely a virus that caused the fever,” says antibiotic resistance expert Olena Moshynets, a microbiologist at the Institute of Molecular Biology and Genetics in Kyiv.

Ukrainian health authorities have sought to curtail this practice, says Moshynets — she notes that fewer antibiotics are now available over the counter in Kyiv, at least. But the same isn’t so in many other regions, says Serhii Shyrinkin, hospital director at Dnipro State Medical University. “We still have a very big problem of people using antibiotics whenever and wherever they want.”

Even before Russia launched its full-scale invasion in February 2022, Ukraine was coping with higher levels of antibiotic resistance than many western European countries. Some extensively drug-resistant strains of Acinetobacter and Pseudomonas now found in wounded soldiers are closely related to strains that were circulating before 2022, according to a July report in Genome Medicine by microbiologist Patrick Mc Gann of the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research in Silver Spring, Maryland, and his colleagues. The findings are “a powerful example of how war and conflict can cause a low-level antimicrobial resistance problem to quickly spiral out of control,” he says.

Ukrainian health officials have recently begun giving physicians clearer guidance on antibiotic usage. Doctors once were left to decide on their own which antibiotics to try against various infections. “It was a complete mess. There was a lot of confusion about what to prescribe and how to treat patients,” says Viktor Strokous, head of the emergency department at Kyiv City Clinical Hospital No. 6, who has treated hundreds of soldiers with life-threatening infections.

In 2023, the Ministry of Health issued guidance dividing available antibiotics into three groups: first-line drugs, a watch list of drugs to be used more sparingly, and antibiotics held in reserve for the toughest cases. “It was a great step forward,” says Strokous. However, Ukraine’s war economy means there are scant resources for importing newer and pricier antibiotics. That means Ukrainian physicians mostly lack access to the most powerful antibiotics used as a last resort in wealthier nations.

Too close to the blasts

Dnipro, Ukraine’s fourth largest metropolis, is an industry-heavy city — and for that reason, it has been hit hard and often during the war. A favorite Russian target is Pivdenmash, an aerospace design center and factory that during the Cold War produced Soviet intercontinental ballistic missiles and Kosmos spacecraft. To its misfortune, Dnipro State Medical University’s hospital sits catty corner from Pivdenmash’s eastern gate. Several times over the past few years, it has suffered damage from blast waves from attacks on the aerospace facility.

On a visit to the hospital in June, some of its shattered windows are still covered with plywood after a missile strike several weeks earlier. In the infection control office, a placard on the wall has a picture of a handgun next to a cup of coffee with the words, in Ukrainian, “How it should be. Coffee — hot. Muscovites — cold.” Ukrainians take their java seriously. Three times, the office’s coffee machine was struck with shards of glass and chunks of window frame, but to the relief of the infection control team, it has kept right on brewing.

Dmytro Balyk, chief of surgery at the Dnipro hospital, shrugs off the vulnerable location. “I don’t have time really to think about it,” he says. The hospital performs up to 50 operations a day, mostly on soldiers. Along with an even larger complex across town, the Mechnikov — one of Ukraine’s biggest medical centers — it receives a stream of war-wounded who have already started treatment elsewhere.

“Our most problematic pathogen is Acinetobacter,” Balyk says. Around one in four patients with this bug have an extensively drug-resistant or pandrug-resistant infection, he says. They are isolated from other patients as best the hospital can manage. In the case of localized infections, treatments include removing dead or infected tissue and negative pressure — creating a vacuum over the wound that suffocates the oxygen-requiring Acinetobacter. Such approaches, coupled with antiseptics and a course of antibiotics, can cure some patients, Balyk says. But for others, especially those whose infections have spread into the bloodstream, “there’s no successful treatment.”

Identifying the right antibiotics for an extensively drug-resistant or pandrug-resistant infection is “very stressful,” says Aliieva, who advises physicians at St. Panteleimon Hospital about which drugs are likely to be most effective and often signs off on their choice. When she started this work a few years ago, she says, “I wanted to cry every day. It blew my mind how huge the problem was.” The hospital’s microbiology lab identifies bacteria in blood and other tissue samples and uses agar plates to determine susceptibility, a process that can take up to a week. For patients whose lives hang in the balance, the hospital rushes samples to a nearby university for a fast turnaround — an hour or less — to identify bacterial strains using a type of mass spectrometer technique called MALDI-TOF MS.

Moshynets and colleague Roman Gulkovskyi, also at the Kyiv Institute of Molecular Biology and Genetics, are working on a tool that would bring rapid diagnosis to the masses. With scientists in four cities in Ukraine equipped with next-generation DNA sequencing machines, they are homing in on specific regions in the genomes of multidrug-resistant strains from Ukrainian patients. First, they are using a commercial test that can identify 364 different resistance genes; the researchers aim to characterize 12,000 samples from Ukraine patients by the end of the year. In a subset of cases, they plan to sequence the entire genomes of the strains they find. “That will give us a complete picture of which resistance genes are most important in Ukraine,” Gulkovskyi says.

Next, based on that information, the molecular biologists plan to design their own Ukraine-specific test kit with just a handful of the most important genes — perhaps 10 — to enable quick diagnosis of bacterial strains infecting soldiers and other patients. “That would tell us which antibiotic available here should be used for each case,” Gulkovskyi says. Most hospitals and clinics nationwide have a lab that can handle these tests, and the turnaround time for getting results can be two to three times faster than with the mass spectrometry technique.

Gulkovskyi hopes that these life-saving test kits can be available next year. But even the rapid detection of a pandrug-resistant strain would still leave clinicians with a thorny challenge.

Perhaps evoking the fiercest dread in Ukraine is pandrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. The bacterium is commonly found among gut flora, and in healthy people is largely benign. But it has emerged as the signature pathogen of the Ukraine war. Around 80 percent of extensively drug-resistant Klebsiella strains in Ukraine carry so-called NDM resistance genes that confer broad resistance to carbapenems.

That rate is “much higher than the rest of Europe,” says Mc Gann. Klebsiella, he adds, did not have to evolve this resistance: The bacterium easily picks up resistance genes from other bacteria in its vicinity. In 2023, Mc Gann’s team helped to investigate the case of a Ukrainian soldier infected with six extensively drug-resistant strains who died after developing sepsis. These included a pandrug-resistant Klebsiella equipped with an NDM gene and a whopping 23 other resistance genes, the team reported in 2023 in Emerging Infectious Diseases.

What makes Klebsiella especially dangerous, Martin says, is its versatility. It causes a range of serious infections, from bloodstream infections and ventilator-associated pneumonia to urinary tract infections and abscesses. Unlike Acinetobacter, Klebsiella can survive without oxygen, so negative pressure treatment doesn’t kill it. “If we see a Klebsiella strain which is sensitive to something, we feel happy,” Aliieva says. “But that’s a very rare situation.”

A two-drug approach

Kyiv may be far from the frontlines, but Ukraine’s capital has come under increasing aerial bombardment. The city has long been an evacuation destination for war casualties. “They arrive here by train and by helicopter, by ambulance and by bus,” says Strokous. Scores of patients with seemingly intractable infections have ended up at Kyiv City Hospital No. 6. Klebsiella is the most pernicious, Strokous says. “Before the war, we didn’t see many Klebsiella infections,” he says. “Now, it’s Klebsiella, Klebsiella, Klebsiella. And the drug resistance is ferocious.”

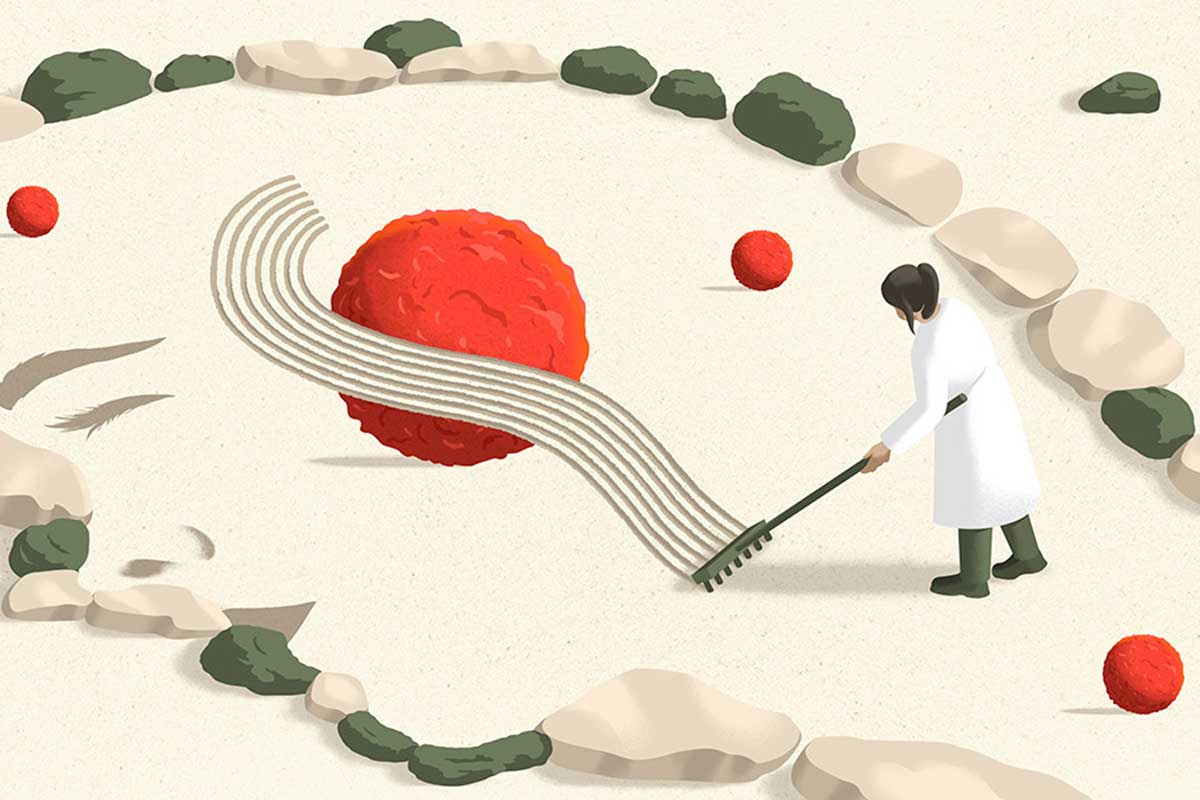

A ray of hope came in the spring of 2023, when Moshynets heard about a soldier in the ICU on the brink of death. Surgeons had stitched up his shrapnel-shredded abdomen, but he had developed signs of sepsis, and tests revealed bacteria impervious to antibiotics. Moshynets’ research suggested that a two-antibiotic combo might vanquish the infection. She urged the soldier’s doctors to try azithromycin, which smothers Klebsiella’s attacks on the immune system and makes the bacterium more susceptible to a second drug, meropenem, a potent carbapenem. The soldier recovered.

Strokous says that he and his team have now treated more than 100 patients with azithromycin in combination with meropenem against Klebsiella, piperacillin/tazobactam against Pseudomonas, and cefoperazone/sulbactam against Acinetobacter. The 90 percent success rate they have seen, he says, is “well beyond our expectations.”

Moshynets is proselytizing the one-two punch to anyone who’ll listen. One new convert is a young orthopedic surgeon at a clinic in Ivankiv, a small town an hour’s drive north of Kyiv.

With his black T-shirt and muscular, tattooed arms, Anton Arestovych looks more like one of the Ukrainian soldiers he treats than like one of his fellow physicians. Many of his patients are injured soldiers from Ivankiv or its surroundings who have lost faith in the care they’ve received elsewhere and are desperate for a second opinion. “Some contact me through social media, and I invite them to our clinic,” he says. By the time they arrive, their infections have often been festering for weeks. “We’re seeing a lot of pandrug resistance,” Arestovych says. “The bacteria are becoming much more aggressive.”

This past March, a soldier hobbled into the clinic with a fractured leg. “He was a mess,” Arestovych says. The fracture had several pus-filled abscesses. Arestovych removed dead tissue and shards of bone, then inserted a surgical spacer that gradually released four antibiotics. But after about a week, he says, “the situation became much worse.” The bandages were tinged with blue and the wound smelled sickly sweet — hallmarks of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Lab results showed that the strain was pandrug resistant, and that the wound was also infected with another gram-negative bug, Proteus mirabilis.

Arestovych went online in search of a Hail Mary. And, he says, “I found Olena.” Moshynets explained how her combo therapy works. The medical director of the Ivankiv clinic was skeptical, but Arestovych was persuaded to give it a shot: “It was that, or amputation.” Ten days of azithromycin and meropenem defeated the Proteus. Arestovych also attacked the Pseudomonas by swapping in piperacillin/tazobactam for meropenem. Two weeks later, the soldier’s infection had cleared up.

Spreading into western Europe

Other parts of Europe have also gotten a rude awakening to the horrific infections that Ukraine deals with day after day, as wounded soldiers are evacuated to hospitals in Germany, the Netherlands and elsewhere.

One example is a young Ukrainian soldier with extensive abdominal injuries and fractures who was transferred to a Dutch hospital for surgery. He’d been infected with 14 carbapenem-resistant strains, including extensively drug-resistant A. baumannii, researchers reported in Infection last April. “It was a really rare case,” says team leader Antoni Hendrickx, national coordinator of the Dutch Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network. At least two of the strains had acquired resistance from other bacteria in the soldier’s body, he says. After five months of various antibiotic therapies, in which the Dutch physicians played whack-a-mole with severe infections flaring up here and there in his body, they finally overwhelmed the microbes and released the soldier into rehab.

Dutch surveillance confirms that drug-resistant Klebsiella is a major concern, Hendrickx says. And it has flagged a rare pathogen in Ukrainian patients, too: extensively drug-resistant Providencia stuartii, a gram-negative bacterium that can colonize burn victims and patients with urinary catheters. Before the war in Ukraine, Hendrickx says, they’d see one or two P. stuartii cases a year. Now it’s 10 to 15. And while Dutch hospitals take great pains to isolate patients from Ukraine, some multidrug-resistant strains have slipped into other hospitalized patients, says Wertheim. “So far, it’s been quite limited, luckily.”

No wonder, then, that Ukraine’s gallery of rogues, both familiar and exotic, has put hospitals across Europe on edge. “I have friends who are plastic surgeons in Germany, and they shut down the whole ward after receiving a Ukrainian patient. They completely decontaminate the ward, because they don’t want an outbreak of the type of bacteria we have here,” Uren says. “So, it’s extremely disruptive to the health systems across Europe.”

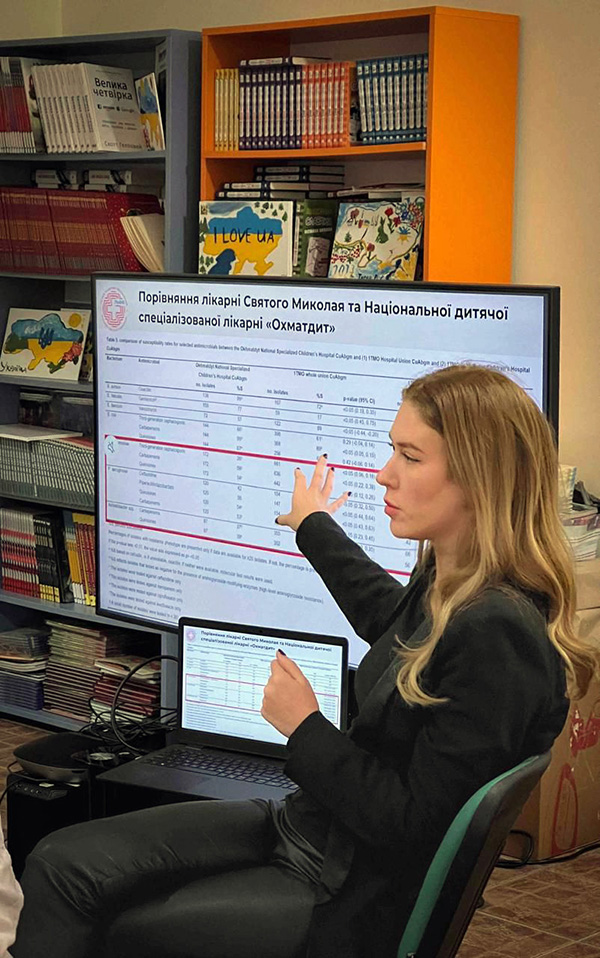

And the situation in the Lviv region has gotten even more troubling. In her office at St. Panteleimon in June, Uren opens a file on her desktop with case reports of children with antibiotic-resistant infections. “Look,” she says, “this is data from our children’s hospital versus one in Kyiv. Obviously, these aren’t military patients.” She rattles through the comparisons, published in the August 2025 issue of the Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. In kids in Kyiv with Klebsiella infections, 59 percent of their strains can be treated with carbapenems, versus only 28 percent in Lviv. Acinetobacter: 37 percent versus 21 percent. Pseudomonas: 53 percent versus 24 percent.

“It’s just really terrifying,” she says. “Our kids have these infections now. They’re getting them from somewhere in the environment.” Treating children is especially difficult because many newer antibiotics are not licensed for pediatric use, says Martin. Thus, treatment often relies on off-label or combination regimens with uncertain efficacy and toxicity.

The threat of an intractable drug-resistant infection in Lviv is clear and present, Uren adds. “I don’t want to be fear mongering, but anyone can be at risk,” she says. “We’re in an era where antibiotics don’t work anymore against some strains.”

A better strategy, Uren argues, is to head off superbugs before they sicken soldiers. “We have to get away from the idea that infections unfortunately go part and parcel with war,” she says. The first step will be to gather intel on which antiseptics and disinfectants are most effective at sterilizing war wounds. Right now, Uren says, “We are cleaning in the dark — what we need to do is prevent contamination from progressing to infection.”

Once that arsenal is clarified, Uren proposes that Ukraine treat wounded soldiers as if they are victims of a bioweapon. Since 2022, Ukraine has received extensive international support for preparedness against an attack with weapons of mass destruction, including hazmat suits and scores of inflatable decontamination tents. Deploying such gear at hospitals and trauma units near the front lines, and applying the right antiseptics and disinfectants, could greatly curtail the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, she says. A pilot effort at a military hospital has just gotten underway. “We can’t afford to lose more limbs and more lives,” says Uren, who relocated to Kyiv at the end of August to spearhead the effort.

One of those two fates was the dreadful prospect facing the British soldier with the shattered pelvis in Lviv this past spring. But his lab report held some encouraging news. He’d been infected with a bug seldom seen in wounded soldiers: Serratia marcescens, a gram-negative bacterium often found on bathroom surfaces. To his good fortune, the strain was susceptible to antibiotics. “It was the best-case scenario,” Uren says.

A setback came in July, when the soldier, on the verge of being discharged from acute care, developed a urinary tract infection caused by multidrug-resistant Proteus mirabilis. He caught another lucky break: Antibiotics vanquished the Proteus and he was transferred to a rehabilitation facility in September.

After rehab, the young man won’t be heading home to the United Kingdom. Instead, he says, he will return to his brigade — and rejoin the fight.

More from Knowable magazine

Recommended for you