The HPV vaccine is erasing cancer – here's the proof

More than a decade after the first HPV vaccination programmes rolled out, data from multiple countries reveals a dramatic fall in cervical cancers and precancers, confirming that HPV vaccines are highly effective and extremely safe.

- 17 November 2025

- 8 min read

- by Linda Geddes

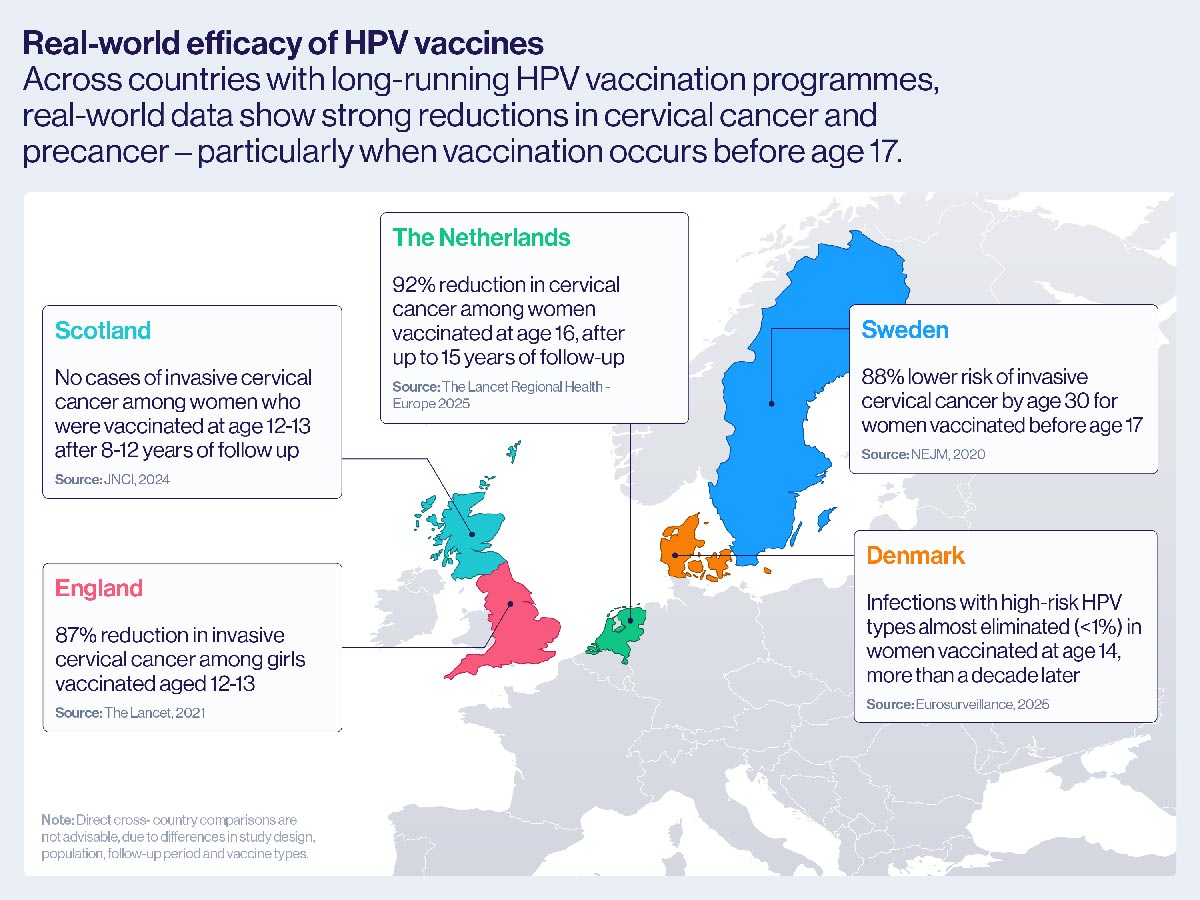

Landmark studies demonstrating the real-world efficacy of HPV vaccines

SCOTLAND: A population-based study of all women born in Scotland between 1 January 1988 and 5 June 1996, linking immunisation, cervical screening and cancer registry data, found no cases of invasive cervical cancer among those vaccinated with the bivalent HPV vaccine (Cervarix) at ages 12-13 after 8-12 years of follow-up.

THE NETHERLANDS: A national linkage study combining vaccination, pathology, and cancer registry data for 103,059 Dutch women, found that those fully vaccinated with the bivalent HPV vaccine (Cervarix) at age 16 had a 92% lower risk of cervical cancer and 81% lower risk of severe precancer after up to 15 years of follow-up, confirming strong protection lasting to at least age 30.

DENMARK: A study of 8,659 women vaccinated with the quadrivalent HPV vaccine (Gardasil) at age 14, and followed through the national cervical screening programme, found that infections with high-risk HPV types were almost eliminated more than a decade later.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines were designed to block the strains of the virus most likely to cause cancer.

But because cervical cancer can take many years to emerge, the full impact of these vaccines – which started being introduced less than two decades ago – is only now becoming apparent.

Multiple studies over the past few years are showing that, for countries that adopted HPV vaccines early on, rates of cervical disease are falling dramatically.

First launched in the United States in 2006 – followed soon after by Canada, Australia, and several European nations – the vaccines now come with nearly 20 years of evidence behind them.

Swedish researchers found an 87% reduction in invasive cervical cancer and a 97% reduction in high-grade precancerous lesions among young women who had the vaccine at ages 12 or 13.

That evidence consistently shows that HPV vaccines are not only safe, but remarkably effective, driving steep declines in both cervical precancers and cervical cancer itself.

Today, more than 158 countries have introduced these vaccines, and that number continues to rise. We chart how the science behind HPV vaccination has evolved, from early clinical trials to real-world data, and what the latest studies reveal about their long-term impact.

Timeline

- 2006: First HPV vaccines licensed in USA, Canada and European Union. USA begins vaccinating girls against HPV

- 2007: Australia, Canada, Belgium, France, Germany and Italy launch national HPV immunisation programmes, followed by further European countries in 2008

- 2009: World Health Organization (WHO) issues a formal position recommending routine HPV vaccination of girls in national immunisation programmes where feasible

- 2012: By 2012, at least 39 countries have introduced HPV vaccine into their national immunisation programmes.

- 2012: Gavi begins funding the introduction of HPV vaccination programmes and demonstration projects in eligible countries.

- 2014: Gavi announces it has supported the full immunisation of more than 3.9 million girls against HPV

- 2016: WHO recommends countries should consider a multi-age cohort, including girls aged 9–14 when they first introduce the vaccine to expedite its benefits.

- 2019: By now, more than 100 countries around the world have introduced the vaccine into their national schedules

- 2022: WHO recommends the option of a simpler one dose schedule

- 2022: Gavi revitalises its HPV programme with over US$ 600 million in additional investment and sets a goal to reach 86 million adolescent girls by the end of 2025.

- 2023: By the end of 2023, 38 countries have launched national HPV vaccine programmes with Gavi support.

- 2025: By November 2025, 158 countries around the world have included HPV vaccination in their national programmes, and Gavi announces they estimate that they have reached 86 million girls.

What did early trials say about the HPV vaccine’s efficacy?

In 2006, the world’s first HPV vaccine – Gardasil – was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

Designed to protect against four types of human papillomavirus (HPV), including the two most common cancer-causing strains (16 and 18), Gardasil marked a historic moment in the fight against cervical cancer.

A year later, the results of a pivotal clinical trial were published in the New England Journal of Medicine. Involving more than 12,000 young women in 13 countries, it suggested that Gardasil was 98% effective in preventing high-grade cervical lesions – precursors to cervical cancer – caused by HPV types 16 and 18.

Efficacy was lower (44%) when women who had previously been infected with these HPV types were included in the analysis – a key reason why the vaccine is offered to girls before they become sexually active.

In Scotland, cancer registry data published in 2024 revealed something even more remarkable. After more than a decade of HPV vaccination, no cases of cervical cancer had been recorded among women who received the vaccine when they were 12 or 13.

These findings proved the vaccine could prevent the early cellular changes that lead to cervical cancer. But what about other dangerous HPV types?

In 2009, a study in The Lancet of another newly approved vaccine, Cervarix – which protects against two high-risk HPV types (16 and 18) – expanded the evidence base.

In a trial of more than 18,000 women aged 15-25, the vaccine not only showed high efficacy against precancers caused by HPV 16 and 18 but cross-protection against three additional cancer-causing HPV types not covered by the vaccine (31, 33 and 35).

This was the first time that an HPV vaccine had shown clear protection beyond its targeted strains – boosting hopes for even broader cervical cancer prevention.

These trials proved that HPV vaccines were effective in controlled settings, but the real test was still to come: how well would they prevent disease in the real world – especially cervical cancers, which can take decades to develop after HPV infection?

How effective are HPV vaccines against cervical cancer?

The first major real-world study was published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2020, drawing on data from Sweden’s national vaccination programme.

Sweden began offering the four-dose quadrivalent vaccine, Gardasil, to girls aged 13 to 17 in 2007. In 2012, the country expanded coverage to girls and women aged 13 to 18, through a catch-up programme, alongside the launch of a school-based vaccination programme targeting girls aged 10 to 12.

Researchers followed more than 1.6 million girls and women over an 11-year period to track rates of cervical cancer among those who had received the vaccine.

Overall, they had a 63% lower risk of developing invasive cervical cancer before their 30th birthday compared to unvaccinated women. Protection was even stronger among those vaccinated before the age of 17, who had an 88% lower risk.

This suggests HPV vaccination has reduced the circulation of these cancer-causing viruses in the Danish general population – so called “herd immunity”.

The evidence didn’t stop there. In 2021, a study published in The Lancet provided real-world evidence of the impact of the two-dose bivalent HPV vaccine, Cervarix, based on national data from England.

The country had launched a school-based vaccination programme for 12- to 13-year-old girls in 2008, and by linking national vaccination, screening and cancer registry records, researchers were able to measure its effect over time.

The Swedish researchers found an 87% reduction in invasive cervical cancer and a 97% reduction in high-grade precancerous lesions among young women who had the vaccine at ages 12 or 13.

The impact was smaller with older girls: those vaccinated between ages 14 and 16 saw a 75% reduction in cervical cancer rates, while those vaccinated between 16 and 18 experienced a 39% reduction.

With mounting long-term data confirming their safety and effectiveness, the science is clear: HPV vaccines work, they are safe and they’re bringing the world closer to ending cervical cancer for good.

Meanwhile in Scotland, cancer registry data published in 2024 revealed something even more remarkable.

After more than a decade of HPV vaccination, no cases of cervical cancer had been recorded among women who received the vaccine when they were 12 or 13.

Although it’s possible some of these women may still go on to develop cancer as they get older, researchers from the University of Strathclyde who carried out the study described it as “strong population-level evidence” that the school-based programme was protecting an entire generation against cervical cancer.

The Netherlands recently added to this growing body of evidence. In 2025, researchers published results in The Lancet Regional Health – Europe analysing more than a decade of national data from more than 100,000 women who had been eligible for the country’s bivalent HPV vaccination programme.

They found that women who were fully vaccinated had around a 90% lower risk of developing invasive cervical cancer than those who were unvaccinated – one of the strongest real-world demonstrations of the vaccine’s impact to date.

How are HPV vaccines protecting the unvaccinated?

As well as protecting vaccinated individuals, emerging evidence suggests that immunisation programmes are generating herd protection – reducing the risk of cervical cancer even among those who remain unvaccinated.

Before Denmark introduced vaccination against HPV in 2008, about 15–17% of its population was infected with the two main cancer-causing HPV types (16 and 18).

However a recent national study, which analysed cervical samples collected between 2017 and 2024, found that the prevalence of these high-risk HPV types had dropped to below one percent among vaccinated women, and to around five percent in those who were unvaccinated.

This suggests HPV vaccination has reduced the circulation of these cancer-causing viruses in the Danish general population – so called “herd immunity”.

Even so, around a third of vaccinated women remained infected with other cancer-related HPV types not covered by the vaccine, indicating that continued but less intensive screening may be required for these women.

Have you read?

Is the HPV vaccine safe long-term?

Nearly two decades since HPV vaccines were first introduced, hundreds of millions of people have been immunised, and scientists continue to monitor populations for any signs of serious side effects.

In the United States, more than 135 million doses of HPV vaccines have been administered since 2006 – including the bivalent Cervarix and the quadrivalent and nine-valent Gardasil – and the evidence remains overwhelmingly reassuring.

Although some people report mild and short-lived side-effects after vaccination – typically soreness, headache or fever – large-scale studies and continuous monitoring have found no causal link between HPV vaccination and serious outcomes such as reproductive problems, persistent pain or chronic illness.

Deaths reported after vaccination have also been thoroughly reviewed, with no evidence that any were caused by the vaccine.

With mounting long-term data confirming their safety and effectiveness, the science is clear: HPV vaccines work, they are safe and they’re bringing the world closer to ending cervical cancer for good.