Saving babies with a US$1 smart glove

A US$1 surgical glove fitted with nanocomposite sensors helps detect fetal position in labour.

- 8 February 2023

- 5 min read

- by SciDev.Net

A low-cost "smart glove" designed to sense the position of a baby during labour could prove a life-saving intervention in places with limited resources, say the UK-based developers.

Around 2 million women a year have a stillbirth and almost half of these occur during labour, according to the UN children's agency, UNICEF. Women in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia bear the greatest burden, accounting for more than three quarters of stillbirths, where a baby is born with no sign of life at 28 weeks or more of pregnancy.

"Out of all the world's stillbirths, 98 per cent occur in low- and middle-income countries and a majority of those are due to what we call obstructed labour," says Shireen Jaufuraully, an obstetrician and researcher at University College London (UCL) who helped devise and test the US$1 smart glove.

"As most low- and middle-income countries are struggling to touch the UN-mandated maternal mortality rate of less than 70 per 100,000 live births coupled with the ever-rising cost of modern healthcare, 'smart gloves' bring hope for most health agencies."

Agnimita Giri Sarkar, consultant paediatrician, Institute of Child Health, Kolkata

The innovative device uses nanocomposite sensors to provide real-time data on the fetal position and pressure exerted on the baby's head, during a vaginal examination.

In an obstructed labour, the baby becomes blocked and can't descend through the birthing canal, resulting in the need for delivery using forceps or a special type of vacuum device known as a ventouse suction cup, or a Caesarean.

"In an emergency situation if you need to deliver a baby, and you are going to put forceps or a ventouse on that baby's head, you need to know what position the baby is in," explains Jaufuraully, lead author of a study on the glove published in Frontiers in Global Women's Health. "If you do put these instruments on the wrong way you can cause trauma to the baby, you can cause trauma to the woman, and you get a failed delivery."

In the case of a failed delivery, an emergency Caesarean section is the only option, which carries a substantially higher risk of complications than a planned Caesarean, Jaufuraully tells SciDev.Net.

Have you read?

Clinicians ordinarily rely on vaginal examinations carried out by hand to try to determine the position of a baby, or they use an ultrasound scanner. However, in low-resource settings, ultrasounds and the medical staff trained to operate them are not always available.

Nanocomposite sensors

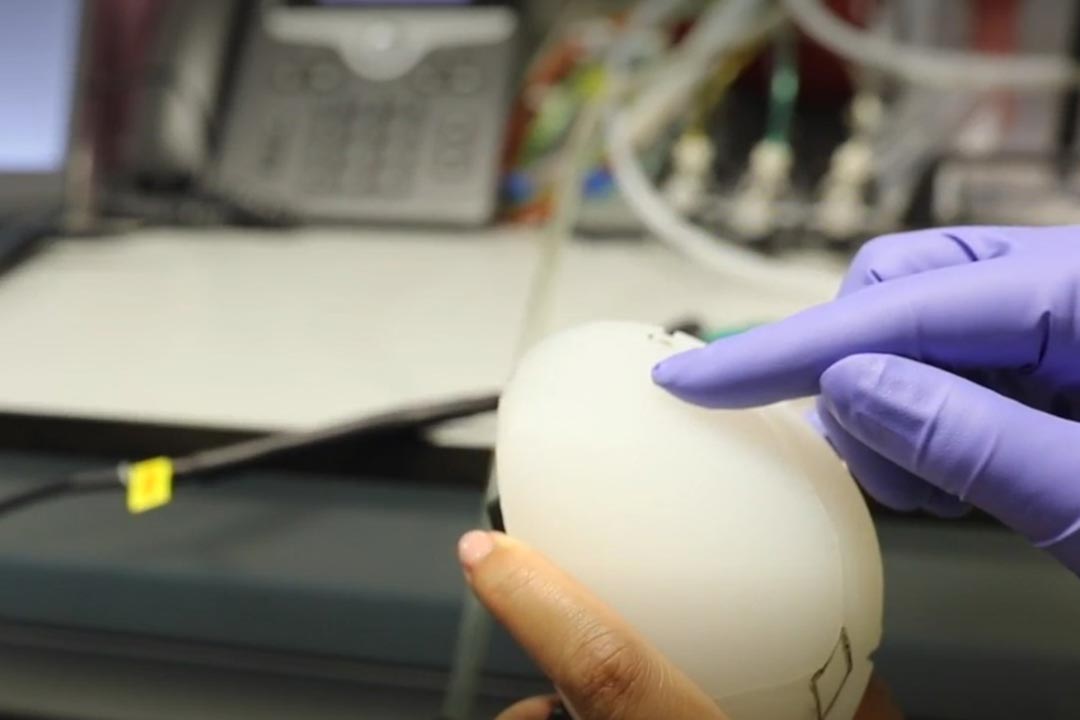

To address this need, the researchers came up with the idea of adapting a simple surgical glove by printing flexible pressure and force sensors onto its fingertips.

The sensors are made of metal-oxide nanocomposites, which generate an electric current when they touch or rub against something. They are designed to be thin enough so as to not interfere with a doctor's sense of touch and a second surgical glove can be worn over the smart glove to keep things sterile.

"We set ourselves the challenge of developing something that was not going to disrupt the clinical work flow and also not interfere with a clinician's own sensory perception," explained Manish Tiwari, a nanoengineering professor at UCL and part of the smart glove team.

Credit: Wellcome/EPSRC Centre for Interventional and Surgical Sciences (WEISS)

"We also wanted to consider the toxicity of materials used, sterility during use etcetera," he added.

They developed a smartphone app so that clinicians can view the sensor data in real time. But Tiwari stressed that the device does not require internet connectivity.

"The gloves used so far are either plugged to a computer or connect wirelessly to a hand-held device," he said. "We still need to develop appropriate security protocols to enable remote data transmission [and] we need to run a number of clinical studies and trials before we can use this in practice. However, the simplicity of the design and inexpensive nature gives us the hope that we may get there."

Jaufuraully added: "There's definitely an unmet need for this. It's about making the diagnosis better, but we hope to improve training as well. We're hoping that with the information that's transmitted by the glove, somebody sitting half way around the world would be able to look at that information and say 'well yes, I think it's a good idea that you go for a Caesarean section or an instrumental birth'."

The study team say they are now undertaking another "low-risk" study using obstetricians, medical students, and midwives to test the glove on models of a baby's head. They expect to embark on a human trial later this year or early 2024.

The researchers put the cost of the smart glove at US$1 based on its production in the lab, but say the cost of mass producing it could be much lower.

Agnimita Giri Sarkar, consultant paediatrician at the Institute of Child Health, in Kolkata, India, described the innovation as "interesting and impactful".

"As most low- and middle-income countries are struggling to touch the UN-mandated maternal mortality rate of less than 70 per 100,000 live births coupled with the ever-rising cost of modern healthcare, 'smart gloves' bring hope for most health agencies," she told SciDev.Net.

"Generating real-world evidence remains a challenge," she cautioned, but added: "If it does cross this barrier, it will truly be a 'smart' weapon for millions of healthcare professionals across the globe."

Written by

Website

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net's Global desk on 8 February 2023.