From vaccines to screenings: how Uzbekistan is transforming cancer care for women

By addressing cervical cancer prevention and expanding efforts to tackle breast cancer, Uzbekistan is setting an example for public health strategies in Central Asia.

- 8 May 2025

- 6 min read

- by Umida Maniyazova

In January 2025, Uzbekistan launched an ambitious programme to combat cervical and breast cancer, building on the momentum of its highly successful HPV vaccination campaign. This initiative marks a significant step in the country’s self-financing era, following support from Gavi during the initial roll-out of the HPV vaccine between 2019 and 2021.

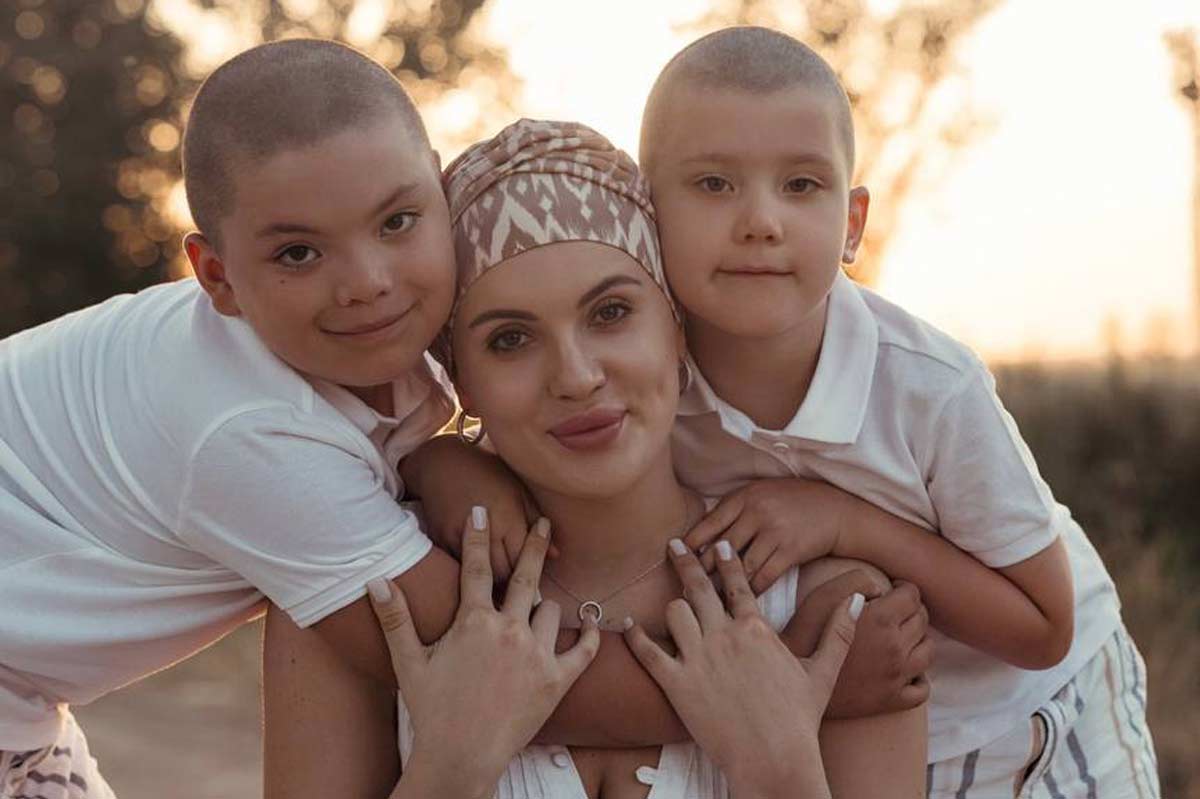

Diana’s story: a personal perspective on early detection

Thirty-one-year-old Diana Bakman from Tashkent understands the life-saving significance of expanded early detection efforts. In May 2024, she was diagnosed with stage II breast cancer, involving five tumours. Bakman, a mother of two young children, says the diagnosis shook her to her core.

“The first thing that came to my mind when I found out about the cancer was my kids. They’re so young, and I kept wondering, ‘Who will take care of them if something happens to me?’ It was a thought that never left me throughout my treatment.”

After a double mastectomy and eight rounds of chemotherapy, Bakman faced a severe complication: acute liver failure. But thanks to the medical team’s efforts, she recovered.

Bakman emphasises that timely screening saved her life. She now actively supports other patients and advocates for the inclusion of immunohistochemistry (IHC) testing in the national programme – a critical diagnostic step for treatment planning, that costs up to 2.9 million Uzbekistani som (about US$ 227) in private clinics.

A protective shield

In Uzbekistan, cervical cancer ranks second only to breast cancer by incidence, killing an estimated 1,103 women each year. Globally, cervical cancer is attributable in almost every case to infection with HPV, and large-scale, long-term studies have shown that widespread HPV vaccination can drive down the incidence of cervical cancer by 90%.

The introduction of the HPV vaccine in Uzbekistan in 2019 was a groundbreaking move to combat cervical cancer. With support from Gavi, WHO, and UNICEF, the Ministry of Health implemented a school-based vaccination programme targeting girls aged 9 to 14.

The results were remarkable: by 2021, 591,478 girls had been vaccinated, achieving a coverage rate of 98.6%. Mild side effects were reported in only 0.1% of cases, underscoring the safety and effectiveness of the programme.

This success was attributed to meticulous planning and community engagement. Teachers played a pivotal role in educating students and parents about the benefits of vaccination, while health workers received specialised training to ensure smooth implementation. Local committees, mahalla committees and religious leaders were brought on board. Public awareness campaigns through social media, television, and printed materials further contributed to high uptake rates.

Ambitious targets

Building on the success of the HPV vaccination campaign, Uzbekistan is now intensifying its fight against breast and cervical cancer.

Aziza Umarova, Head of the Delivery Unit at the Agency of Strategic Reforms under the President, is also one of the initiators of the cancer control programme among women. She mentioned that it took a full year of dedicated efforts to develop this initiative.

HPV vaccination campaign has laid a strong foundation for Uzbekistan’s new initiative against cervical and breast cancer. Based on medical recommendation, the me will aim to extend HPV vaccination efforts to include boys within the target age group, in addition to girls. It will also introduce nationwide screening to facilitate better early detection of both cancers in women. This government-designed programme supports the implementation of the “Uzbekistan-2030” Strategy.

“As part of this initiative, step by step, women within specific age groups will be invited for cancer screening and systematically followed throughout the full continuum of care – from initial screening through to final treatment. Gynaecologists will conduct both cervical and breast cancer screenings to ensure a comprehensive approach. Cervical cancer screening will be provided at ages 30, 40, and 50 using HPV testing and liquid-based cytology, while breast cancer screening with mammography will begin at age 45.

“National screening and cancer registry data will be utilised to inform policy decisions and improve health outcomes. The programme includes updated treatment protocols and clearly outlines the responsibilities for diagnostics and care. A robust national monitoring and evaluation system will promote accountability and measure effectiveness. Key targets include screening more than 70% of eligible women, ensuring over 90% of diagnosed individuals receive timely treatment and achieving early detection in 60–70% of cases. Notably, this is the first public health initiative to incorporate explicit accountability metrics for reporting,” said Umarova.

“A sun in the black sky”

Rano Kayumova, a physician in Tashkent who specialises in ultrasound diagnostics, calls the new programme “a sun in the black sky”. She believes it could become a significant step in providing women with the necessary medical care to turn back the tide of female cancers, but also raises concerns about whether the budget will be sufficient to support these ambitious plans. “If this [strategy] can be implemented, our country will have no equal in treating oncological diseases in women,” she says.

Umarova too acknowledged several challenges that could hamper the programme’s success and sustainability. “Sub-optimal financing mechanisms for treatment, the lack of immunohistochemistry in the public oncology hospitals, limited professional support and clinic-level training for oncologists, and insufficient clarity around diagnostic procedures and treatment protocols, could hinder consistent implementation across the healthcare system. However, the programme is intended to run until 2030 and aims to establish a clearer, more functional system that improves coordination and ultimately increases the cancer survival rate among women.”

To cope with foreseen challenges, health authorities have set ambitious goals for 2025 to further strengthen the initiative. These include:

- Vaccinating an additional 150,000 girls and women against HPV;

- Establishing breast cancer screening centres in all regional hospitals; and

- Training 5,000 health workers in cancer detection and treatment.

Since the introduction of the national HPV vaccination programme in 2019, Uzbekistan has been using the quadrivalent Gardasil vaccine to protect against human papillomavirus (HPV). Gardasil covers four HPV types-6, 11, 16, and 18 – offering protection against the strains most commonly associated with cervical cancer and genital warts.

At a vaccination site in Tashkent’s Mirzo-Ulugbek district, nurses administer HPV vaccines to young girls while simultaneously educating mothers about breast cancer prevention. “We’re not just giving vaccines; we’re building trust,” says nurse Malika Ismailova. “Many women come back with their daughters after hearing about our work.”

Have you read?

“Every woman in Uzbekistan deserves access to these services”

Аccording to the World Health Organization (WHO), in 2022, breast cancer claimed the lives of 2,246 women in Uzbekistan.

Bakman’s journey highlights the critical importance of Uzbekistan’s expanded cancer initiatives, which aim to provide nationwide screening and treatment by 2025, building on recent successes in HPV vaccination campaigns.

With chemotherapy costs reaching US$ 1,400–2,800 per cycle, the government’s push for free access represents a lifeline for thousands of women. For those battling these illnesses, the cost of medical services and medications often becomes a primary concern.

“Every woman in Uzbekistan deserves access to these services,” says Bakman, emphasising the importance of nationwide initiatives to combat cancer.

Bakman now dedicates her time to supporting other patients, highlighting that early detection, community education and comprehensive testing can turn the tide against the disease.

Despite progress, challenges remain. Anti-vaccine activists continue to spread myths about vaccine safety and efficacy, creating pockets of resistance in rural areas. To counter this, Uzbekistan’s Ministry of Health has intensified its outreach efforts by engaging religious leaders and community influencers to dispel misinformation.

Another hurdle is ensuring equitable access to services across urban and rural areas. While cities like Tashkent have well-equipped facilities, remote regions often lack resources.

The government has pledged to address this disparity by deploying mobile screening units and increasing funding for rural healthcare infrastructure.

Uzbekistan’s comprehensive approach aligns with WHO’s global call to eliminate cervical cancer as a public health problem. By combining vaccination with screening and public education, the country aims to reduce annual cervical cancer cases by at least 30% by 2030.

More from Umida Maniyazova

Recommended for you