A decade of progress: rotavirus vaccination transforms child health outcomes in Uzbekistan

In 2014, Uzbekistan introduced routine rotavirus vaccination with Gavi’s support. Ten years later, the now entirely self-financed programme is going strong.

- 20 December 2024

- 7 min read

- by Umida Maniyazova

This year marks ten years since the rotavirus vaccine was incorporated into Uzbekistan’s national immunisation schedule. Now a well-established part of the national routine immunisation schedule, leaders and parents alike say it continues to make a measurable impact on the health of children in the central Asian country.

“It really makes a difference”

Rotavirus is a leading cause of severe diarrhoea in young children worldwide, and Uzbekistan has not been spared its effects.

Prior to the vaccine’s introduction, rotavirus infection imposed a significant burden on the healthcare system and posed serious risks to children’s well-being. However, with the vaccine’s inclusion in the national immunisation programme, the country has observed a marked reduction in rotavirus-related hospitalisations and fatalities among children.

“My older daughter, who’s now 11, didn’t get the rotavirus vaccine when she was little. When she started daycare at 2.5 years old, she caught the virus and it was awful. She got so sick, and I ended up catching it too. We both had to stay in an infectious disease hospital – it was such a tough time for our family. But with my younger child, who’s now four, we made sure to get the vaccine. Thankfully, we haven’t had to deal with anything like that again. It really makes a difference," said Nargiza Alimova, Tashkent resident.

According to the Ministry of Health of Uzbekistan, the country uses two vaccine products for immunisation against rotavirus infection: Rotarix, administered in a two-dose schedule typically at two and four months of age, and RotaTeq, provided in a three-dose schedule.

“My older daughter, who’s now 11, didn’t get the rotavirus vaccine when she was little. When she started daycare at 2.5 years old, she caught the virus and it was awful. [...] with my younger child, who’s now four, we made sure to get the vaccine. [...] . It really makes a difference.”

- Nargiza Alimova, Tashkent resident

Laying the groundwork

Representatives of the World Health Organization (WHO) in Uzbekistan noted that ahead of the vaccine’s roll-out in 2014, extensive efforts were undertaken to inform the population about this new intervention. Public awareness campaigns were critical. To build trust and understanding, detailed information about the vaccine’s composition, efficacy and safety were disseminated through lectures and community meetings.

Educational materials were distributed in Uzbekistan’s three most widely spoken languages – Uzbek, Russian and Karakalpak. This multilingual approach ensured that information reached diverse communities, contributing to a positive reception of the vaccine. One of the key advantages of this vaccine is its oral administration, eliminating the need for injections and making it generally more acceptable to parents and children alike.

However, the vaccine does also come with specific technical challenges. It must be administered before a child reaches six months of age – with WHO recommending that the first dose be administered as soon as possible after a baby reaches six weeks of age – meaning that primary health care (PHC) providers needed additional training on how to ensure timely vaccination.

Baseline: 700 child deaths a year

Dr Renat Latipov, a National Officer for WHO, highlights that the groundwork for introducing the rotavirus vaccine began as early as 2009 – six years before the introduction.

Studies aimed at assessing the burden of rotavirus infection were conducted not only in Uzbekistan, but also in neighbouring Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan to provide a baseline understanding.

Surveillance sites were established in Tashkent and Bukhara, where all children hospitalised due to gastroenteritis were included in research efforts. Findings revealed that up to 21,000 children under five years old were hospitalised annually due to diarrhoeal diseases, with only severe cases involving dehydration being admitted. This represented a considerable burden for a country with a population of less than 30 million at the time.

Further analysis indicated that rotavirus was responsible for at least 32,000 visits to primary care physicians, and over 330,000 cases of diarrhoea treated at home each year. Tragically, approximately 700 deaths annually were attributable to rotavirus infection.

Before vaccination, rural health clinics reported an average of 20 diarrhoea cases per week; after vaccination, this figure dropped to just five cases per week.

Impact

The introduction of the vaccine initially led to a significant reduction in hospitalisations. This metric later returned to pre-vaccine levels – not due to vaccine inefficacy, but because hospitals, finding they had capacity, began admitting milder cases. PHC data provided a clearer picture of the vaccine’s impact than hospital statistics. Before vaccination, rural health clinics reported an average of 20 diarrhoea cases per week; after vaccination, this figure dropped to just five cases per week.

According to data provided by Dilorom Tursunova, head of the Vaccine Logistics and Immunoprophylaxis Department of the Committee for Sanitary and Epidemiological Welfare and Public Health under the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Uzbekistan, rotavirus vaccine coverage levels have fluctuated over the years since introduction.

As of 2023 – the latest official annual coverage statistics made available by WHO and UNICEF – rotavirus vaccine coverage in Uzbekistan stands at 89%.

2023 statistics provided by the Ministry of Health reveal that diarrhoeal disease incidence among children under five has decreased to approximately 10,000 cases annually, despite Uzbekistan’s population growing to nearly 37 million due to increased birth rates. This represents a more than 50% reduction in disease prevalence against the baseline, directly reflecting the effectiveness of vaccination efforts.

Have you read?

Indirect benefits

The rotavirus vaccine has also demonstrated indirect benefits. As an oral vaccine, it stimulates immunity in the gut, which may enhance resistance to other infectious agents. This phenomenon mirrors observations from the use of oral polio vaccines in the past. Consequently, the rotavirus vaccine not only protects against its target virus but also contributes to broader immune resilience in children.

Dr Latipov emphasises that the vaccine’s dual impact – direct protection against rotavirus and general immune strengthening – has significantly improved child health outcomes in Uzbekistan.

Remarkable achievement

WHO experts regard Uzbekistan’s immunisation programme as one of the most effective globally.

General routine vaccination coverage in the country – conventionally proxy-measured by the third dose of the diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis-containing vaccine – stands at 99%, a remarkable achievement by international standards.

Uzbekistan: Gavi graduate

While Gavi supported the rotavirus vaccine introduction in 2014–15 (as well as the introduction, in years since, of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, inactivated polio vaccine and human papillomavirus vaccine), that programme is now run independently of Vaccine Alliance funding.

In fact, since 2020, when Uzbekistan transitioned out of core Gavi support, the national immunisation programme has been largely flying solo.

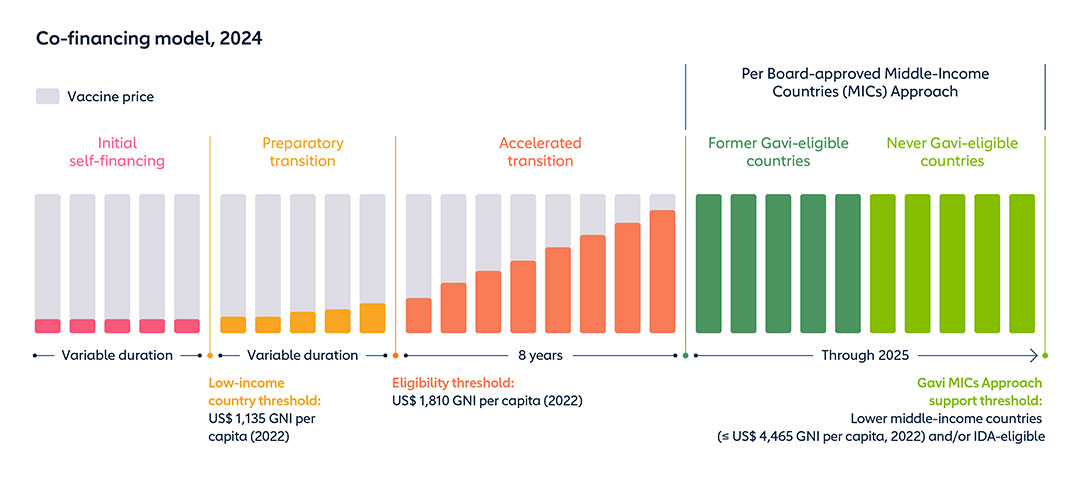

What does that mean? Gavi’s support model is designed to help country health systems get vaccines to the people who need them for as long as they need – not forever. So, as a given country’s economy expands, and it becomes more capable of shouldering the financial burden of buying vaccines (still the best investment going in health), it pays a greater share of that bill, with Gavi covering the rest. After stepping into the “accelerated transition” phase – a step triggered by a country’s own economic indicators – that country has eight years to make the jump out of Gavi assistance.

But even so-called “former Gavi countries” remain eligible for specific kinds of help. While Uzbekistan levelled up out of core Gavi support in 2020, it received support through COVAX to pull together a COVID-19 immunisation programme during the pandemic, and has also received bits of funding to shore up its programme’s sustainability – for instance, by building out its vaccine cold chain.

Achieving such coverage levels is no small feat and reflects substantial efforts by healthcare personnel and programme administrators. The success of Uzbekistan’s immunisation initiatives can be attributed to meticulous planning, robust public engagement and stringent quality assurance measures.

The introduction of the rotavirus vaccine in Uzbekistan has significantly transformed the country’s approach to managing diarrhoeal diseases among children under five. With consistently high vaccination coverage and a marked decline in rotavirus-related cases over the past decade, Uzbekistan’s immunisation programme stands out as a global model of success, showcasing the profound impact of coordinated public health initiatives on improving child health outcomes.

More from Umida Maniyazova

Recommended for you