Why integrating nutrition and immunisation can be a game-changer

The case for integration is clear, but a new review outlines ways to find more evidence to support policy changes

- 21 November 2023

- 3 min read

- by Gavi Staff

Malnutrition and killer infectious diseases claim the lives of millions of children in low- and middle-income countries every year, yet most of these deaths are preventable.

Nutrition and immunisation are closely linked. Vaccines may not trigger strong immunity in children who are malnourished, yet children with poor nutrition tend to be most vulnerable to infectious diseases and need protection from vaccines. Often, the children that specialised immunisation programmes are trying to reach are also the least likely to have access to food and nutrition services.

In many settings, immunisation programmes delivered in remote or hard-to-reach areas can be a gateway to providing wider primary health care services.

This week, the Eleanor Crook Foundation (ECF) and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance jointly released a review to explore the research on pairing nutrition interventions with vaccine delivery to save more lives. While the benefits of integrating immunisation and nutrition are now well accepted, there is limited information on what works well – this is what the review aims to provide.

Here are the four main recommendations from the report.

1. Create a virtuous cycle by co-delivering nutrition and immunisation interventions

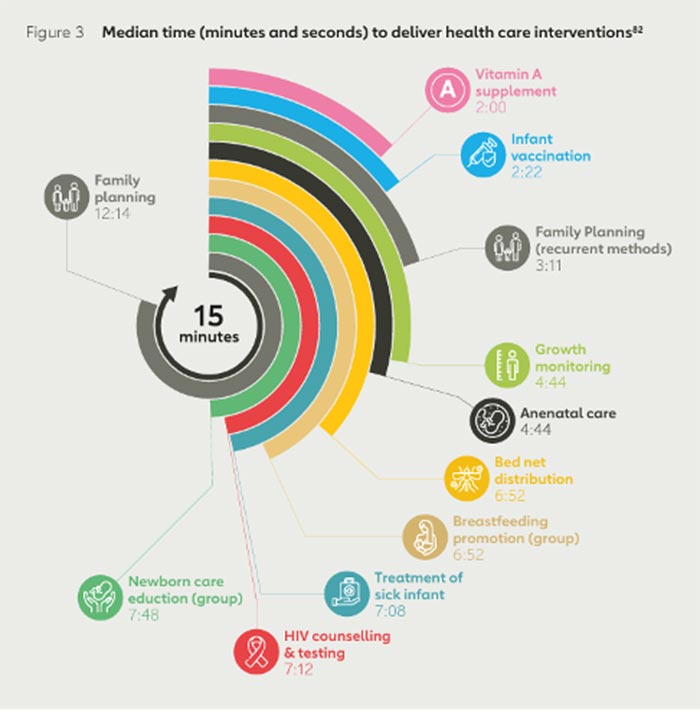

As the children missing out on essential vaccines and nutritional supplements are often the same, co-delivery could amplify the healthcare delivered. This would build on robust evidence of the benefits of integrating Vitamin A supplementation into immunisation platforms.

2. Generate demand through a holistic primary health care approach

There has been a global push to strengthen primary health care in recent years with the intention of harmonising the health care provided to communities in a way that is well rounded and serves all their needs, rather than sporadic, ad hoc single-issue delivery of services. In many settings, immunisation programmes delivered in remote or hard-to-reach areas can be a gateway to providing wider primary health care services.

3. Use a proactive learning agenda that helps build the evidence base

More evidence is needed on how to integrate nutrition and immunisation. The review recommends testing using nutrition services as an incentive for using immunisation services, and testing approaches where one service's touchpoint with the community is used to screen for and refer to the other service. This will be especially important in communities with large numbers of malnourished, under-immunised or zero-dose children, as they tend to have little contact with health services.

4. Generate evidence on the impact and cost benefit of integration.

While integration makes logical sense, evidence is limited so far. Yet this is crucial to guide future policy and investment and for addressing concerns from programme stakeholders focused on potential disruption to existing, siloed services. As many donors focus on vertical programmes, researchers often only measure or report on the effect of the integration on the primary intervention. Generating evidence on dual impact will require donors to collaborate to generate this evidence, which should include also an analysis of the financial and non-financial costs of integration.