Two Indias: Looking after mothers in rural Chhattisgarh and urban Bengaluru

The disparity may be colossal but in both places care is built on trust and good information.

- 17 October 2023

- 7 min read

- by Sweta Daga

"When I go to meet expectant mothers, I try to explain to them that a 'tikka' or a shot is important, because it saves us from dangerous diseases, especially our children," says Santoshi Gandharv, a senior Village Health Worker from Semaria, a village in Bilaspur district, Chhattisgarh.

"The women who stay and deliver in the jungles are at high risk of infections, as the treatment-seeking is compromised due to long distances and other barriers."

– Rajkumari Oraon, maternal and child health worker

"Many of them don't know that getting a vaccine for their newborns – especially for diseases like tuberculosis or polio – can save their life, so I make sure they understand."

Gandharv's work here, where health indices lag the national average, is vital.

Vulnerability in numbers

Chhattisgarh, a large state in central India, has a predominantly Adivasi or "tribal," population, a demographic umbrella term referring, in India, to indigenous groups who are often socially and economically disadvantaged. According to the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5) for the period 2019–2021, more than 77% of Chhattisgarh's population is rural.

While the all-India under-five mortality rate in 2019–2021 stood at 41.9 per 1,000 live births, in Chhattisgarh, it was higher: here, 50.4 children in every 1,000 died before their fifth birthdays. India-wide, 18.1% of women were recorded as underweight; in Chhattisgarh, that figure stood at 23.1%. And then, Chhattisgarh women had less help in pregnancy: 65% of Chhattisgarh women who had been pregnant in the five years of the survey reported having had an antenatal check-up in their first trimester. The equivalent India-wide figure was 70%.

Gandharv and others like her are a critical link in a vulnerable healthcare chain. Known to her colleagues and patients as Santoshi didi, which means "elder sister", Gandharv has been a community health worker for 23 years. She is employed by a health NGO called Jan Swasthya Sahyog (JSS), but her work is comparable to the role performed in other communities of the state by government-employed Accredited Social Health Activists or ASHA workers.

"Almost invisible"

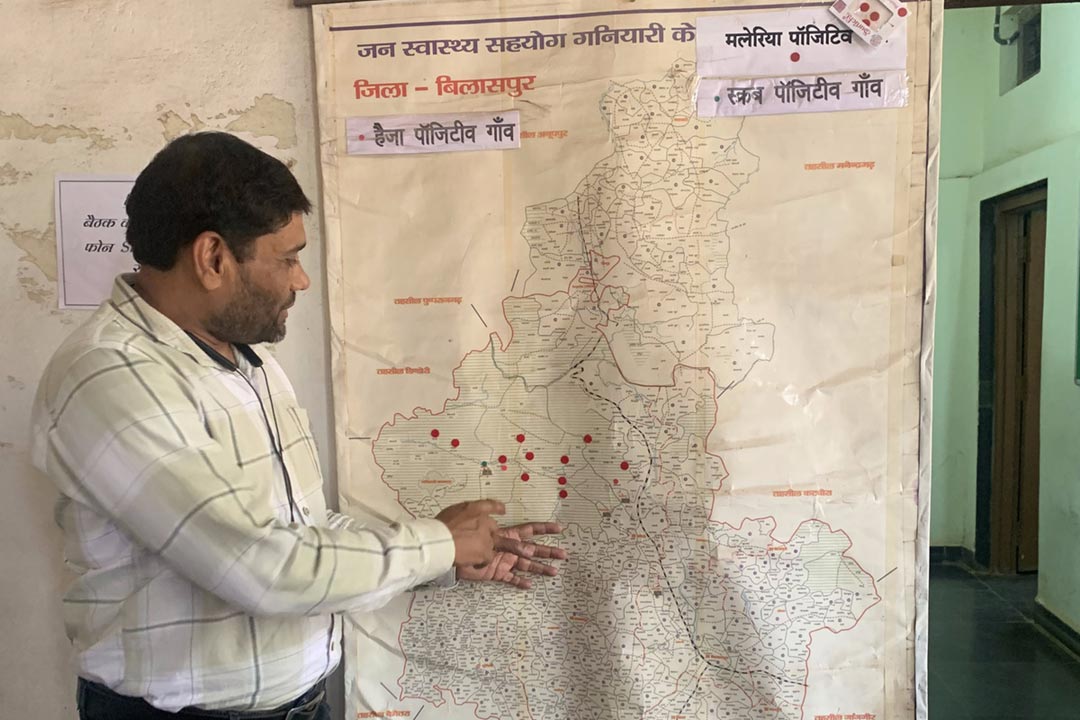

Here in Bilaspur district, JSS runs an intensive community health programme covering 72 forest and forest-fringe villages, home to a population of 40,000.

Minal Madankar, a public health professional working as Maternal and Child Health Programme Coordinator with JSS, says most of the residents in these villages are from tribal communities or other groups designated as particularly marginalised.

"Most of the people are from the Gond tribe, followed by Oraon tribes and Baigas. [These are] known as Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTGs), who live in the interior forest villages.

"Before JSS, the healthcare system was almost invisible in this area," says Madankar. "The communities were very shy and vulnerable in all senses. Over the years we tried to recreate a robust health and health care system in these villages with Village Health Workers (VHWs) supported by our referral hospital in Ganiyari."

Choosing trust

JSS has 146 VHWs, she explains, each of whom is elected by the community to serve them. "Trust is the main component of becoming a village health worker," says Madankar. "The village gets together and votes on who they think is best, not based on education qualifications, but based on the women's relationships in the community. We then train the women to look out for minor ailments like cold and cough, or fever ,but also how to recognise chronic diseases like TB, hypertension, and diabetes during their regular village rounds."

Since the village health worker is plugged into the community, they know which couples have married, and begin to visit those homes to find out if the women need support or have missed a period. If a woman is found to be pregnant, she is registered for antenatal care clinics run by JSS.

Have you read?

Rajkumari Oraon, a maternal and child health worker, says, "The women who stay and deliver in the jungles are at high risk of infections, as the treatment-seeking is compromised due to long distances and other barriers. We ensure that the woman knows about all the vaccines they need, including tetanus, and of course vaccines for their newborns like BCG, polio, and hepatitis B."

Jungle to urban high-rise

Puja,* a midwife in private practice in Bengaluru, an urban metropolis in the relatively wealthy southern state of Karnataka, now works with predominantly well-to-do women, but previously she worked for a month with JSS in Chhattisgarh. "The urban-rural divide really stood out to me when I did a month of work with JSS. Nutrition was the biggest difference I saw. Women in Bengaluru have access to a wide variety of food and in the tribal areas [of Chhattisgarh]. Although it seems counterintuitive, they were not eating as many fruits and vegetables."

While in Bengaluru, she routinely dedicates a large part of one of her second-trimester visits to the topic of vaccination. She explains why she finds routine jabs to be an even more indispensable intervention in more deprived contexts. "The health of the mother directly impacts the health of her unborn baby in utero. If the mother – in her childhood and through her adult life – has been malnourished or undernourished, the health of the baby is impacted. Access to vaccines for both the mother (during pregnancy) and baby (after birth) can be life-saving, especially when there are chronic deficiencies in a community. Vaccinations can boost the body's ability to develop immunity and fight infections, which may not be fatal if a child is well-nourished, but can have a debilitating impact on a child who doesn't have access to nutritious food."

There are further disparities. "Access to healthcare, of course, is also a big factor, but more than that, it is the access to information that is important."

"Access to healthcare, of course, is also a big factor, but more than that, it is the access to information that is important."

– Puja,* midwife in private practice in Bengaluru

Most of her clients in Bengaluru have higher levels of what she calls "mainstream education" than the women she encountered in Bilaspur district. She clarifies that she isn't dismissing forms of knowledge that circulate in the tribal areas: "In Chhattisgarh there is generational wisdom," she says. But in both contexts, she insists, access to good, clear, comprehensible information is vital.

"I practise something called 'informed decision-making', which means that my role as a midwife is to give the parents all the relevant information and help them navigate the decisions they have to make." Explaining vaccination, for instance, she uses a lot of visual aids and diagrams to surmount any potential language barrier. "There is a lot of misinformation out there, and many times parents do their own research and come with questions."

In Bengaluru, as in village Chhattisgarh, a bond of trust nurtured between mothers and health workers is indispensable. "The best thing I found to do is to focus on the mother entirely," reflects Puja. "It's entirely about the relationship we develop with the mother and family, and when we talk about something as confusing as vaccines, medicines, nutrition – it can be overwhelming. Patience is key."

Huge disparity

JSS has made major strides combatting communicable diseases and malnutrition in Bilaspur district, Puja says, "but the disparity [between rural Chhattisgarh and urban India] is still huge".

Dr Nafis Faizi, an Assistant Professor and Epidemiologist from Aligarh Muslim University who specialises in community medicines and health systems, says that disparity is a deeply entrenched one.

"Health care has always been better in Karnataka. The health system differences and trust in health services differ widely between Karnataka and Chhattisgarh. Other than that, the social differences in terms of economic condition, literacy, participation and health system accountability differences are also existent. This reflects clearly in the NFHS-5 data as well. Deprivation and discrimination mired in intersectional challenges in access and affordability are far more [prevalent] in Chhattisgarh than in Bengaluru.

"In Bilaspur only 46.9% of mothers had their recommended four antenatal care visits as opposed to 81.8% in rural Bengaluru," he continues. "When we compare vaccinations, only 52.5% of children in Bilaspur are fully vaccinated, compared to over 90% in Bengaluru."

The fact that a child is far more likely to survive past age five in Bengaluru than in Chhattisgarh is influenced by women's health, and complicated again by nutritional deficiencies and inadequate social provisions. "The gaps get more pronounced with each deprivation," he explains.

"We also often miss out on women's health. Many programmes are guilty of focusing on reproductive health alone, reducing the overall importance of women's health."

* Name changed