How the answer to long-lived immunity to COVID-19 could lie in our bone marrow

People who have had COVID-19 seem to have bone marrow cells that could produce antibodies for years to come, which could mean that immunity both from natural infection and vaccination is long lasting.

- 31 May 2021

- 3 min read

- by Priya Joi

What is the research about?

A sharp drop in antibody levels after COVID-19 infection has led to concerns that immunity to natural infection may not be very long lived, sparking concern among scientists that the duration of immunity following vaccination may also be short. Encouragingly, immunity induced by COVID-19 vaccines seems to last for at least six months, and probably a lot longer. Studying antibody production in people who have had COVID-19 can offer clues as to how long immunity could last.

The scientists found that although antibodies decline rapidly in the first four months after infection and then more slowly over the next seven months, they are still detectable at least 11 months after infection.

What did the researchers do?

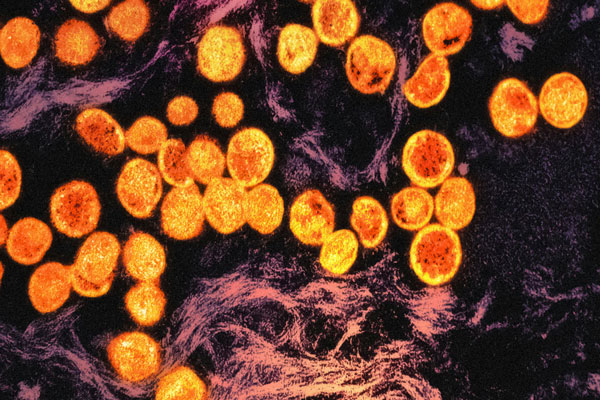

Researchers writing in Nature collected blood samples from 77 COVID-19 patients – most of whom had mild illness – about a month after they first showed symptoms. They were looking for antibodies to SARS-CoV-2. Antibodies are made by plasma cells, but not all plasma cells are the same. Immediately after infection, short-lived plasmablasts make antibodies that fight the immediate infection, but in this study the researchers were interested in looking for the presence of long-lived plasma cells that live deep in our bone marrow. These bone marrow plasma cells can potentially generate antibodies for years, even decades, after infection.

What did they find?

The scientists found that although antibodies decline rapidly in the first four months after infection and then more slowly over the next seven months, they are still detectable at least 11 months after infection. The researchers collected memory B cells and bone marrow from 18 patients of the group and, crucially, in 15 of the samples they found ultra-low but detectable populations of bone marrow plasma cells that had been triggered by COVID-19 infection 7-8 months previously. These cells were still present when the scientists looked again several months later.

Have you read?

What does this mean?

The researchers believe this an important finding in terms of potential long-term immunity both from infection and from vaccination given that bone marrow plasma cells can potentially continue to produce antibodies for decades. While this is a promising signal, researchers will need to continue to track this closely in the coming months and years to see whether bone marrow plasma cells persist. Also, new variants may mean that the presence of these cells are not enough, and people will need additional doses of vaccines to boost immunity.

More from Priya Joi

Recommended for you