Nipah vaccines set to enter human trials

Scientists are racing to combat one of the world’s deadliest viruses with two groundbreaking new vaccines.

- 15 July 2025

- 6 min read

- by Priya Joi

Two vaccines against Nipah virus – a deadly bat-borne virus – are set to enter human clinical trials in Bangladesh, while promising drug candidates have shown potential to treat and prevent infection.

While case numbers of Nipah remain relatively small, climate change is altering habitats, bringing the fruit bats that carry and spread the virus in South-Asia and South-East Asia more into contact with people. An estimated 2 billion people are at risk of this deadly infection.

The race for vaccines and treatments is critical given the latest Nipah outbreak in Kerala, India, where earlier this month health authorities confirmed two cases – one of whom died. Over 400 people are currently under surveillance.

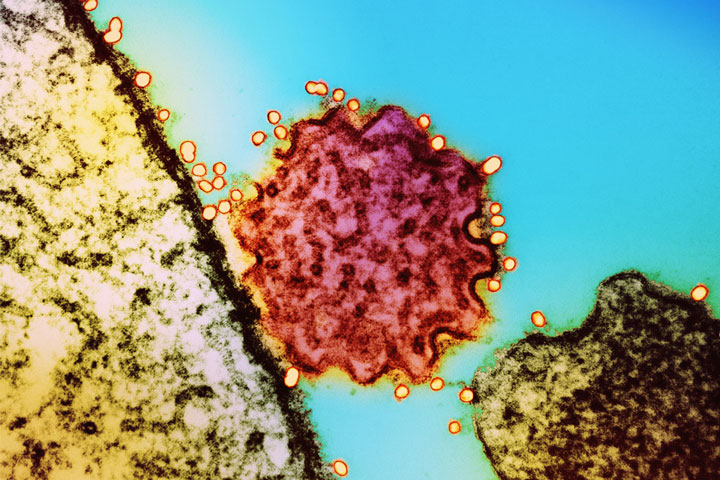

Nipah has a high fatality rate – it is capable of killing 75% of people it infects – and the World Health Organization (WHO) considers it a priority pathogen with the potential to drive mass outbreaks.

Even when infection isn’t fatal, the virus can leave a brutal aftershock; months after being declared Nipah-free from previous outbreaks in India, two people remain in a coma.

Growing risk

Bangladesh and India have had the highest number of outbreaks and cases from Nipah virus so far.

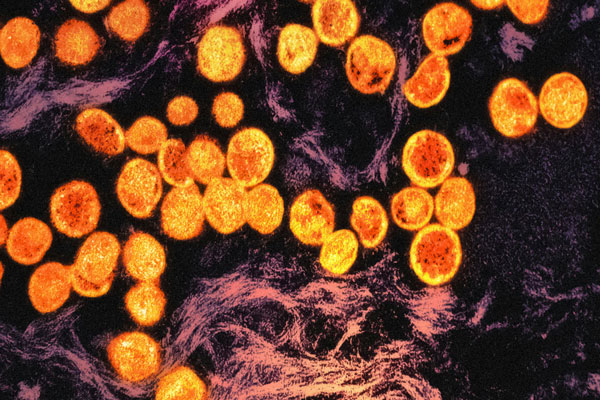

The virus is harboured by fruit bats, which can spread it to humans through contact with bat droppings or contaminated food or water. Once a person is infected, it generally spreads through close contact – the virus can jump from person to person via droplets released when coughing.

The disease can start as an acute respiratory infection, progressing to seizures and fatal encephalitis (inflammation of the brain).

While case numbers of Nipah remain relatively small, climate change is altering habitats, bringing the fruit bats that carry and spread the virus in South-Asia and South-East Asia more into contact with people. An estimated 2 billion people are at risk of this deadly infection.

Vaccines in development

The ChAdOx1 NipahB vaccine, developed at the University of Oxford and based on the same vaccine platform as the ChAdOx1 COVID-19 vaccine developed with AstraZeneca, has just been given support from the PRIority MEdicines (PRIME) scheme by Europe’s medicines regulator, the European Medicines Agency (EMA).

Professor Brian Angus, the trial’s Principal Investigator, told VaccinesWork that the PRIME designation will be important in helping to accelerate the regulatory approval of the vaccine. There is compelling animal data and preliminary clinical evidence from the Phase 1 trial that is currently wrapping up.

Specifically, says Prof Angus, “where the EMA’s support and the PRIME designation will be really useful is in developing an animal model to lead to licensure”.

Development of the ChAdOx1 NipahB vaccine has been funded by the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), as part of its mandate to counter epidemic and pandemic threats.

Have you read?

While the human trials due to start in Bangladesh will be important in demonstrating safety, Prof Angus says “it could be challenging to show the clinical efficacy of the vaccine given the small number of cases of Nipah there have been so far. This is where a reliable animal model is going to be important for licensure – as happened with the chikungunya vaccine, for instance.”

Emergency potential

Vaccines that are still being tested can be approved for emergency use in certain circumstances, as was done with the Ebola vaccine in response to the outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

“Based on available Phase 1 data, it would be possible for the Oxford Nipah candidate to be administered to high-risk individuals – with informed consent and under strict clinical trial protocols which would have to be approved by regulators – in response to the recent Nipah outbreak in Kerela,” Dr Nicole Lurie, CEPI’s Executive Director of Preparedness and Response and US Director, told VaccinesWork.

“However, this decision would lie with the Indian authorities who would consider the benefits and risks of this approach, and would have to balance how such an approach would complement existing and proven containment procedures.”

“It is important to note that, while we are optimistic,” Dr Lurie adds, “we do not yet know for sure that the vaccine is effective.”

Prof Angus explains that whether a vaccine that’s still being tested could be approved for emergency use depends how big the outbreak is.

“If we’re in a situation where Nipah is spreading very quickly, then the risk aversion might be a little bit lower than if – as it has been in the past – there are only one or two cases.”

Effective public health measures, which Kerala is known for deploying with Nipah, can control small outbreaks. “The Indian Council of Medical Research have a mobile BSL-4 laboratory [the highest level of biosecurity containment] that they drive down, which is very impressive,” he says.

“So there’s the ethical issue of, if public health control is working well, would you deploy a vaccine until you know for sure it’s safe and effective? It probably is. But that’s what we are testing now in human and animal trials.”

Prof Angus’s team are also investigating a two-dose regimen of their Nipah vaccine (where the second dose acts as a booster) to protect people at high risk of Nipah such as healthcare workers or bat surveillance teams.

Extra preventive power

CEPI is also funding the development of a vaccine called PHV02 that is based on the same technology as the approved Ebola vaccine, rVSV-ZEBOV, which has been used to fight previous Ebola outbreaks.

PHV02 vaccine is a live, attenuated, recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus (rVSV) vector that expresses the glycoprotein of the Nipah virus (Bangladesh strain) to trigger immunity to this virus, but it also expresses the Ebola virus glycoprotein, which could mean it could potentially be used to fight Ebola too.

PHV02 is also about to start Phase 2 clinical trials in Bangladesh.

Monoclonal antibodies are another promising therapeutic for Nipah, because they could they be used “alongside vaccines as a so-called immunological bridge – offering immediate protection before the onset of longer-lasting vaccine-induced immunity – to help contain viral spread, says Dr Lurie.

In their use as a ‘short-term vaccine’, monoclonal antibodies could offer protection from infection for at least three months, she says, but they can also be used to treat people infected with Nipah.

Back in the Oxford Vaccine Group, the team are using the ChAdOx1 platform to test vaccines for Lassa fever, MERS, Rift Valley Fever and Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever, although Nipah is the most advanced, he says.

“The advantage of using the same sort of basic vaccine structure and slotting in different antigens for different diseases means that the lessons you learn in one area can be used in another. So it’s quite an exciting time.”

More from Priya Joi

Recommended for you