How Nigeria’s Nasarawa state took on hepatitis

An ambitious five-year viral hepatitis elimination plan in northern Nigeria‘s Nasarawa State has led to a reduction in hepatitis B and C burdens, including among people living with HIV.

- 7 May 2025

- 7 min read

- by Afeez Bolaji

In 2017, Rafatu Abdullahi,1 a middle-aged trader from Doma Local Government Area of Nasarawa State in northwest Nigeria, learned she was HIV-positive, and resolved to square up to her diagnosis. She took her antiretroviral drugs religiously and vowed to live a normal life, against all odds. But as the years rolled by, her viral load kept increasing, despite consistent treatment.

Frustration set in; then lethargy. Abdullahi skipped drugs and had almost thrown in the towel when a state government health intervention – a viral hepatitis elimination programme – reignited her hope.

“I was placed on HIV treatment in 2017 at Doma General Hospital and was checking my viral load, but it was not suppressing,” she recounts. “Shortly after the hepatitis programme started in 2020, I was screened at the hospital, and it was discovered that I was also infected with hepatitis C, which was successfully treated. After some months, I started seeing much improvement in the HIV treatment. My viral load has been going down steadily.”

“Silent killer”

Viral hepatitis is a ‘silent killer’ that claims 1.3 million lives yearly, making it the second only to tuberculosis for deadliness among infectious diseases globally. More than 91 million people live with hepatitis B or C – the two deadliest of the five strains of the virus – in the WHO African region, accounting for 26% of the global burden.

Nigeria has a prevalence rate of 8.1% and 1.1% for hepatitis B and C respectively, among adults aged 15–64 years, while more than 80% of over 20 million people living with both strains of the liver-damaging virus don’t know their status.

In line with WHO’s global hepatitis strategy, which aims to reduce new hepatitis infections by 90% and deaths by 65% by 2030, Nasarawa State, in partnership with the African Union and the Egyptian government, developed a five-year HCV (hepatitis C virus) elimination plan in 2020. Their goal: to treat 124,000 people.

“We’ve achieved micro-elimination”

The scheme, according to Dr Akpan Nseabasi, an epidemiologist who is serving as the programme officer for the state’s hepatitis initiative, seeks to eliminate hepatitis C among about 60,000 people living with HIV (PLHIV) in the state, treat locals with hepatitis B and vaccinate those who are negative.

“So far, we’ve achieved micro-elimination among over 16,000 PLHIV. We screened them and did some ancillary investigations, like liver function tests and a full blood count, and placed them on drugs. We targeted about 12 general hospitals, but we have to phase it by starting with six because the programme is capital-intensive.

“Out of the six general hospitals, we’ve been able to achieve micro-elimination in three hospitals domiciled in three LGAs. The other three facilities are already en route to achieving micro-elimination, which means that once we achieve that, we should have quite a bigger number. While we are doing the micro-elimination among the PLHIV population, we adopt a village-outreach approach for hepatitis B and C,” Nseabasi told VaccinesWork.

The village outreach has also recorded some success, Nseabasi explained, with over 20,000 people screened for hepatitis B and C. He said the 2020–2024 elimination plan has been extended to 2029 to cover more people.

“We target selected communities. We vaccinate, and link people to care. Vaccination is for hepatitis B. In this regard, we have visited over six LGAs selected based on high hepatitis burden. We plan to do this exercise across all the LGAs. In a community called Shabu in Lafia LGA, we screened 2,539 persons. Over 1,500 tested positive for hepatitis, and they were placed on treatment. We vaccinated 852 that tested negative for hepatitis B.

“Treatment of [chronic] hepatitis B is lifelong. So we only provide free drugs for some months, but the state has subsidised the cost of drugs for both hepatitis B and C. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B programme is also ongoing in many health centres,” Nseabasi added.

Locals share bittersweet experience

Salamatu Musa was among those who tested positive for hepatitis B in Shabu community during a mass screening in October 2023 at the community’s primary health centre, and received free drugs that lasted two months. Musa said she felt disappointed when she did not get another batch of free medications.

“Since then, I have been treating it out of my pocket. I buy the prescribed drugs and go for check-ups periodically. The viral load is reducing, but I can’t afford to use the drug regularly because of its cost. If I take it for a month, I stop for two months till I have the means to buy another one,” she explained.

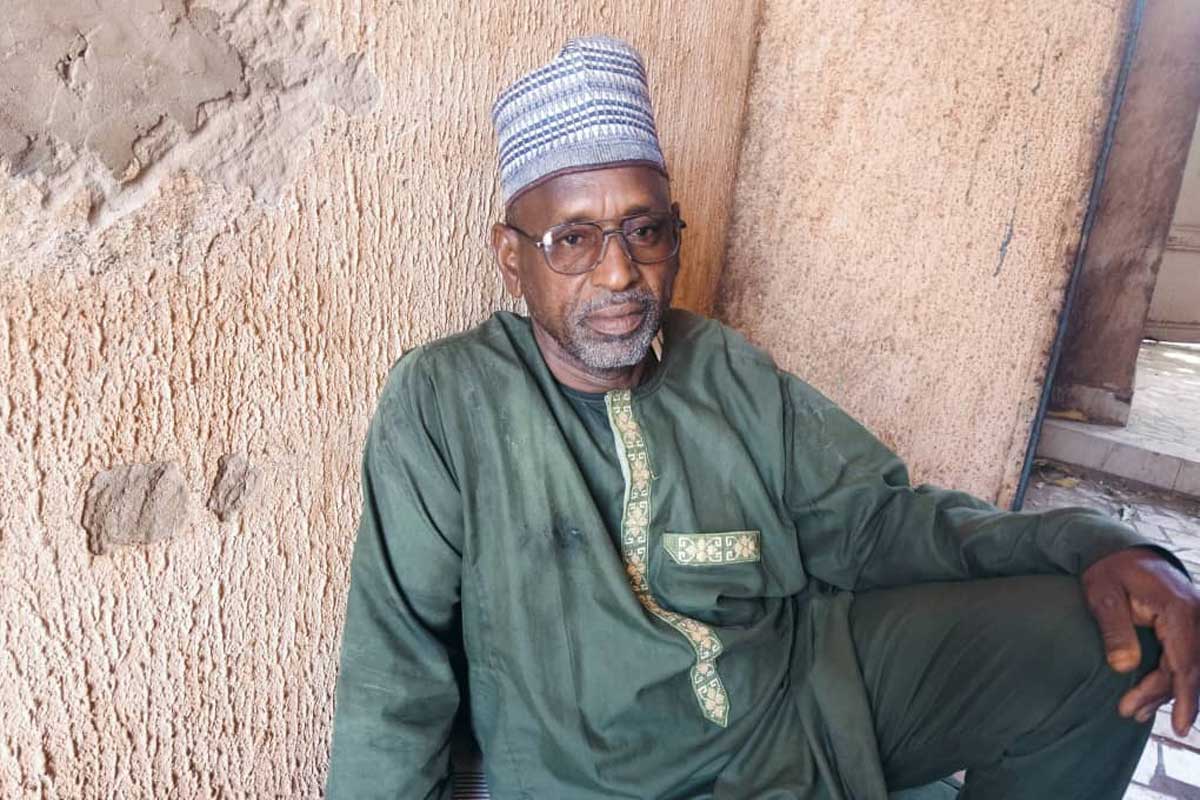

Abdulkadir Abeh, chairman of the ward development committee (WDC) that supervises health facilities in Shabu, said he was cured of hepatitis C after completing his treatment and also received hep B vaccine, and appealed to the government to resume free screening and treatment in his area.

“Hepatitis is a silent killer, and people have been dying here. We see the programme as a messiah to help us eradicate hepatitis. People trooped in for screening and treatment. And as a result, hepatitis has reduced tremendously in our areas.

“I’m now hepatitis C negative, thanks to the programme. I also received three doses of the hepatitis B vaccine. People who tested positive received free drugs. But after a while, drug distribution stopped,” Abeh explained.

Mustapha Shettima, a professor of medicine who specialises in Hepatitis B and liver cancer studies at the college of health sciences, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, advised that preventive measures should be observed to avoid the costs that come with treating hepatitis.

“Vaccination is the most effective way of preventing hepatitis B. But there are other measures to prevent it and hepatitis C, which has no vaccine yet. Blood should be properly screened and negative for hepatitis before it is transfused. People should avoid unprotected sex, avoid using unsterilised needles and sharing sharp objects with people because hepatitis B and C can be transmitted through these means. Prevention is the best. The government should increase the rate of vaccination, make vaccines available and educate people to go for vaccination,” he said.

Reaching people living with HIV in isolated communities

One of the major challenges for health workers was getting PLHIV in hard-to-reach communities screened, as many of them live in places without telecommunication networks, said Donald Agondo, head of the medical laboratory at Doma General Hospital. Some of them, reached by proxy, could not afford transport fare to the hospital either, he added.

“We did follow-ups to get them to come for hepatitis screening and gave them stipends for transportation. Some patients were not doing well on their HIV treatment because they were co-infected [with hepatitis] without knowing. So during the programme, those discovered to be positive were treated, and are now doing well. About 280 patients were screened, and 37 of them were co-infected with HCV and HIV. They were all treated successfully for HCV. We hope the programme will resume.

“Currently, pregnant women are enrolled in free hepatitis B screening, and a number of them are positive. Their husbands and children have also been invited for testing. Those who test negative are being vaccinated, and as soon as drugs are available, we will contact those infected.

“Generally, we have been encouraging people to come forward for testing. The earlier they discover their hepatitis status, the better, because hepatitis resides in the liver. The longer it stays there, the more harm it causes. But if it is discovered on time, the drugs can actually prevent progression of liver damage, and the patients can live a normal life,” he said.

Have you read?

A boost for routine immunisation

Dr Damila Adi, the health ministry’s permanent secretary in Nasarawa, told VaccinesWork that the adoption of the viral hepatitis elimination plan has also contributed to the scaling up of routine immunisation in the state.

“We are leveraging [the hepatitis elimination plan] to educate women. We tell them to ensure that their children receive the hep B vaccine within 24 hours after birth. The awareness of hepatitis has enhanced routine immunisation generally. Penta3 [the third dose of pentavalent vaccine against five killer diseases: diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, hepatitis B and Haemophilus influenzae type B] uptake in the state is now about 73%, up from 31%,” Adi said.

A clinician at Shabu PHC, Salisu Habu, agreed with Adi, saying the programme has increased awareness of hepatitis.

“It is a laudable initiative. People from neighbouring communities and nearby states thronged to Shabu to participate in the hepatitis screening. More people now show up at the health centre to check their hepatitis status, and we have been referring new cases [to higher hospitals].

“We need more test kits, drugs and vaccines. The programme has also boosted routine immunisation. Mothers are bringing their children for vaccination as and when due,” he added.

1 Name changed at her request

More from Afeez Bolaji

Recommended for you