A six-in-one vaccine is rolling out in low-income countries: here’s why it’s a game-changer

The same protection in fewer vaccine doses means being able to maximise the impact of every dollar spent on immunisation.

- 11 July 2025

- 5 min read

- by Priya Joi

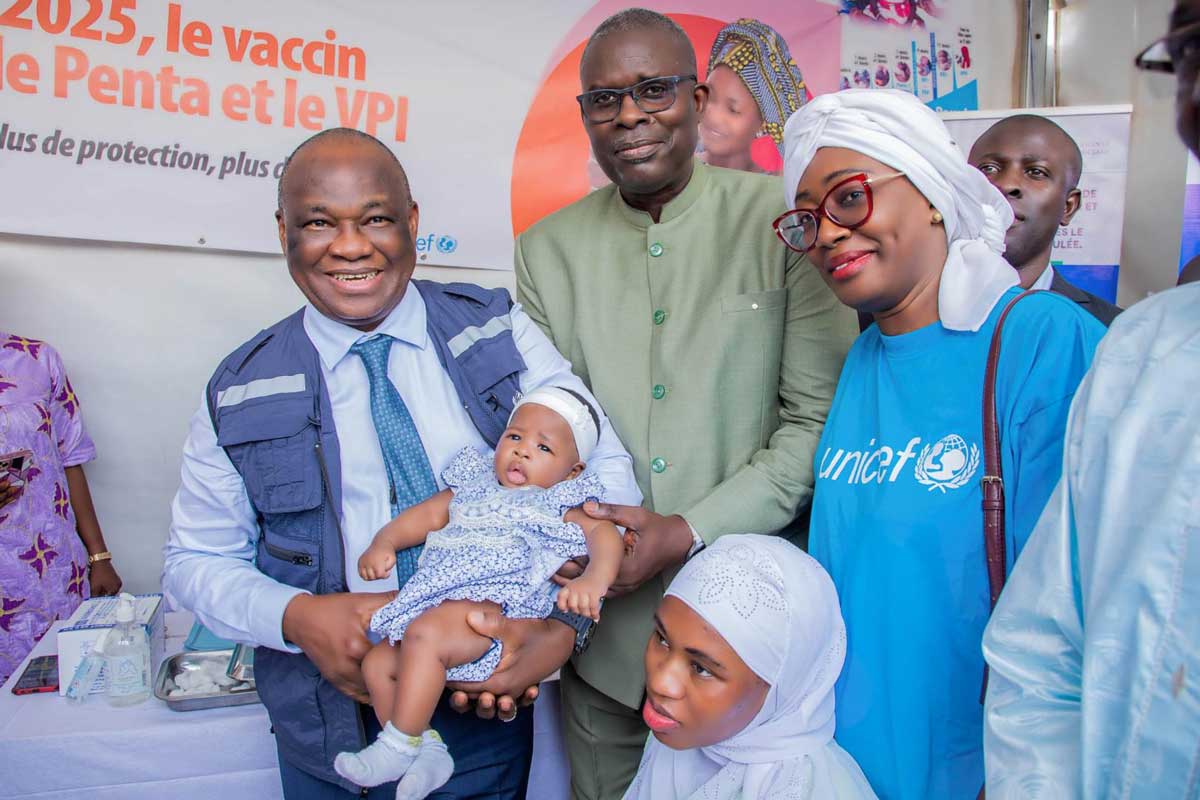

On 1 July, the hexavalent vaccine was rolled out in Mauritania and Senegal with Gavi support. This marks the first time this lifesaving six-in-one vaccine has been distributed in low-income countries.

The combination vaccine protects against six diseases: diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis (whooping cough), hepatitis B, Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib), and poliomyelitis. It replaces the five-in-one pentavalent and inactivated polio vaccines (IPV), previously administered separately.

Creating the market

Katy Clark, Senior Programme Manager at Gavi, told VaccinesWork why this will make such a difference: “The hexavalent vaccine is more than just the sum of its parts. This isn’t just about adding one antigen to an existing combination vaccine.”

Clark explains that there has been an enormous effort by Gavi and partners in market shaping – reassuring manufacturers by creating the foundation of a healthy market for the vaccine – to bring this vaccine to low- and middle-income countries.

“This is a quintessential example of how Gavi creates markets for vaccines that otherwise wouldn’t reach these communities,” Clark adds.

“Another key achievement here is in ensuring vaccine equity,” says Clark. “It wasn’t fair that high-income countries have had this combination vaccine for more than 20 years, while lower-income countries have had to wait.”

A crucial element is that for Gavi countries this six-in-one vaccine needs to include inactivated whole-cell pertussis bacterium (DTPw), which is the form of vaccine that Gavi supports to protect against whooping cough.

Evolution of vaccine protection

The diphtheria, whooping cough and tetanus combination vaccine (DTP) has been administered to millions of children around the world for decades.

According to a recent Lancet study, DTP-containing vaccines have saved over 40 million lives globally in the last 50 years. Since 2000, Gavi-implementing countries have ensured over 1.4 billion children have been protected with the vaccine.

Gavi began supporting pentavalent vaccines in 2001, which combines DTP with Hib and hepatitis B vaccines, in 2001. The goal was to boost the low uptake of Hib and hepatitis B in low-income countries by folding them into routine immunisation programmes.

Now, rolling out the hexavalent vaccine is “the natural trajectory of vaccine evolution”, says Clark. “And this comes back to vaccine equity. Gavi aims to provide the most vulnerable populations the best available vaccines, no matter the socioeconomic status or geographic location.”

Better for both individuals and health systems

Broadly, the biggest benefit of the hexavalent vaccine is in streamlining the process of vaccination. Having several vaccines bundled into one (and three injections instead of five) has multiple benefits.

While vaccines remain one of the best value-for-money investments in health, some of the biggest barriers to their uptake are often basic issues of access or complexity of dosing schedules.

In low- and middle-income countries, families often struggle to get to health centres for multiple vaccinations, a challenge that is exacerbated in areas of migration, displacement or conflict.

For some children who have little interaction with health systems, a combination vaccine such as the hexavalent vaccine could mean the difference between robust protection from deadly childhood illnesses or being left vulnerable.

Multiple vaccines also cost more in numerous ways – cost of reagents, storage, transportation, human resources and so on – which is a barrier both for individuals and governments in ensuring adequate immunisation coverage.

A six-in-one vaccine could also ensure that by administering fewer vaccines, health workers are less prone to errors in vaccine administration. This is especially important in rural or understaffed clinics, where health workers manage large patient loads.

With fewer injections and visits, tracking immunisation status becomes more straightforward, improving data accuracy and enabling better follow-up for missed doses.

There is another critical issue in being able to protect children with fewer injections: a lower risk of vaccine hesitancy. “A trend we’re seeing in many countries is the interest in ensuring the same protection with fewer injections,” says Clark.

Fewer jabs means fewer injection-site reactions, fewer painful experiences for children and needle-stick injuries, all of which makes the experience easier for families and enhances trust among children, caregivers, and health workers.

Have you read?

Protecting children more efficiently

The switch to the hexavalent vaccine is also a boost for the global effort to eradicate polio. It means that inactivated polio vaccine (IPV), a cornerstone of the polio eradication effort, should reach more children on time and more efficiently.

This is important because until now, children have been protected against polio either by oral polio vaccine (OPV) or IPV, but OPV will be phased out in the coming years.

Combining IPV with pentavalent in the form of the hexavalent vaccine increases access to IPV for under-immunised children, especially in places where DTP coverage exceeds IPV coverage (average coverage for all three doses of the DTP vaccine is 83% vs. 42% coverage of the second dose of IPV).

“Health-seeking behaviour around polio is already low because the polio programme has been effective at eliminating much of the virus transmission, which means people don’t perceive it as a problem,” says Clark.

The problem, she says, is that if fewer children are vaccinated against polio, it could mean that the virus takes hold again and starts to become the major global health threat it once was.

The delivery schedule of hexavalent could also mean that children are better protected against poliovirus.

For most Gavi-supported countries, IPV is given first at 14 weeks of age and the second dose at nine months. Uptake for the second dose is much less than for the first dose, says Clark, perhaps because it happens many months after the initial cluster of vaccinations and health checks for babies.

Since the last dose of hexavalent is at 14 weeks, this should impact the number of children who complete the course.

As low- and middle-income countries are seeing rising rates of diseases like diphtheria, “it’s never been more important to continue to roll out life-saving vaccines like hexavalent.” says Clark. “Public health works when kids don’t get sick, and this has been a successful vaccine in all its iterations. This is a win for public health.”