100 years and counting of mask wearing in Japan

As wearing face masks in public becomes the new normal across the world, what can we learn from a country like Japan, where this has been a long-established practice?

- 19 February 2021

- 4 min read

- by Tetsekela Anyiam-Osigwe , Jacques Schmitz

The deadly virus first emerged in China, but quickly spread far and wide. New York declared a state of emergency, London’s hospitals were reaching full capacity with infected patients and in Japan the virus spread from crowded cities to much smaller urban areas. This was not COVID-19, but a dangerous new influenza (H3N2) virus with “an unusually high attack rate” – known commonly as the Hong Kong flu – which ran rampant across the world in the late 1960s.

Children even took masks to school on a weekly basis and there was little need to impose fines on adults to get them to wear masks.

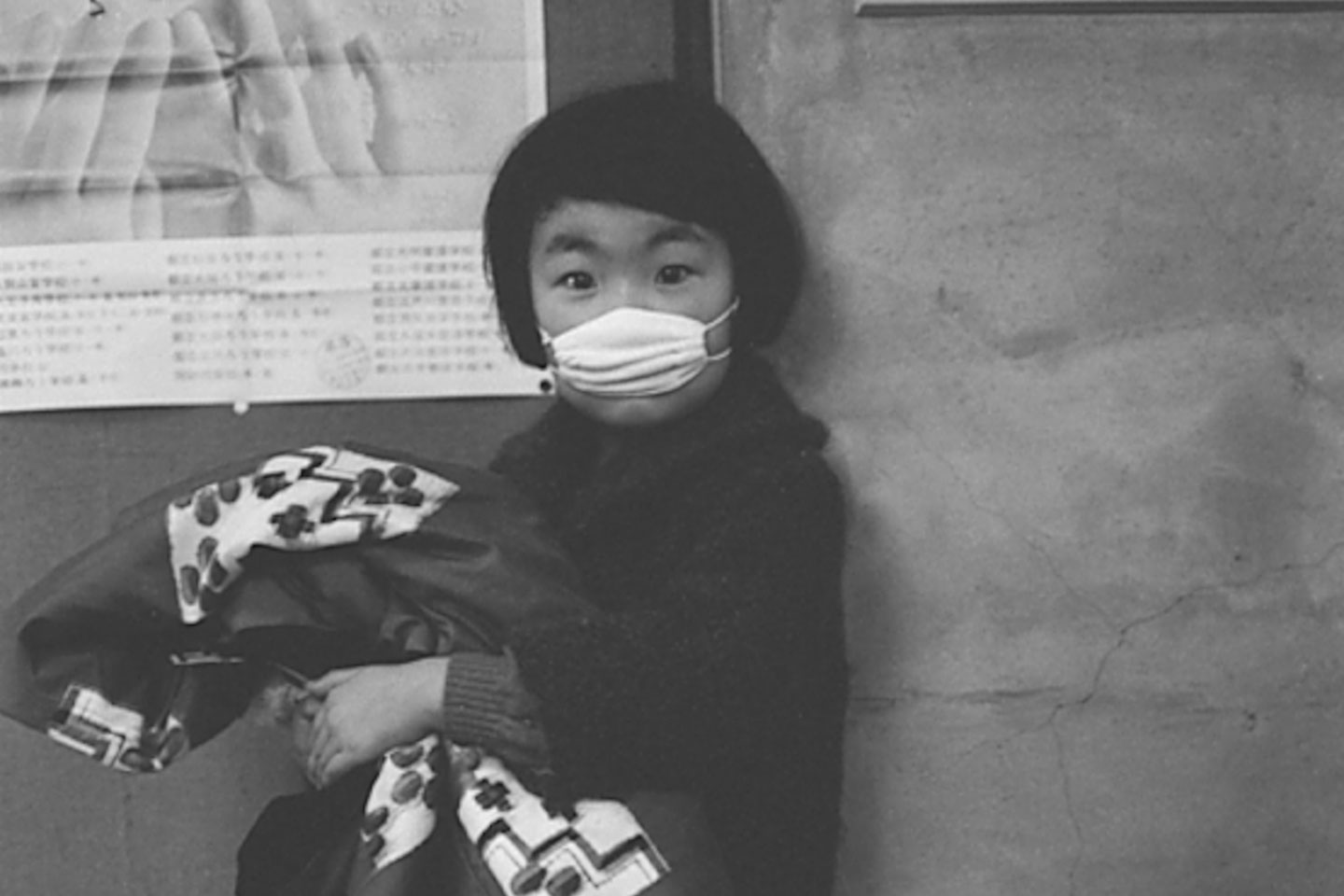

Although more than a dozen cases of the H3N2 virus had been reported and confirmed between August and September 1968, it was not until October that an actual epidemic started in Japan. In Tokyo, then the world’s largest city, authorities were preparing to face a major public health threat. The dense concentration of nine million inhabitants made the city particularly vulnerable to contagious viral infections. Before a vaccine against H3N2 had been developed and made available, Japan turned to face masks to help contain the spread.

Credit: WHO/Paul Almasy

This was not the first time that Japan faced a major viral threat, and nor was it the first in which the use of face masks was instrumental in curbing its spread. The Hong Kong flu was the third influenza pandemic to occur in the 20th century. The first was the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918. Then, in the absence of a vaccine, the widespread use of masks proved crucial in containing the virus.

From San Francisco, with mask orders: Japan responds to its first 20th century pandemic

Even though the use of facemasks in Japan can be traced back to before the 20th century, it was the Spanish influenza pandemic between 1918 and 1920 that significantly altered the status of wearing masks.

Have you read?

This shift was triggered by the search for effective ways to contain the influenza pandemic. By the autumn of 1918, Japan’s National Public Health Bureau, learning from cities like San Francisco that successfully responded to the pandemic through mask orders, took action. Local authorities across Japan were directed to encourage people to wear masks in hospitals, on trains and trams, and in crowded areas. A year later, free masks were provided to those who could not afford them, and theatres, buses and cinemas were added to the list of public places where wearing masks was mandatory.

Doctor’s note: masks work

Over the next century, a series of major public and global health threats and crises across East Asia, including the 2003 outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and swine flu in 2009, further cultivated a culture of mask wearing among the general public in Japan. Ultimately, wearing face masks came to symbolise a collective and targeted defence against the invisible threat of pandemics.

It’s not difficult to see why; wearing face masks can be an effective measure to reduce transmission. By providing an additional layer of protection, they can help to prevent the wearer from spreading viral infections to others, which is particularly useful in high-risk circumstances where physical distancing proves impossible and the level of ventilation is either minimal or unknown.

From Tokyo, with love: everyone has a part to play in the 21st century

Authorities in Japan began to use public health campaigns in earnest to encourage the use of masks in the early 2000s. There was a growing push for people to understand that their individual actions mattered, not only for their own health but also for the health of their communities and the country at large.

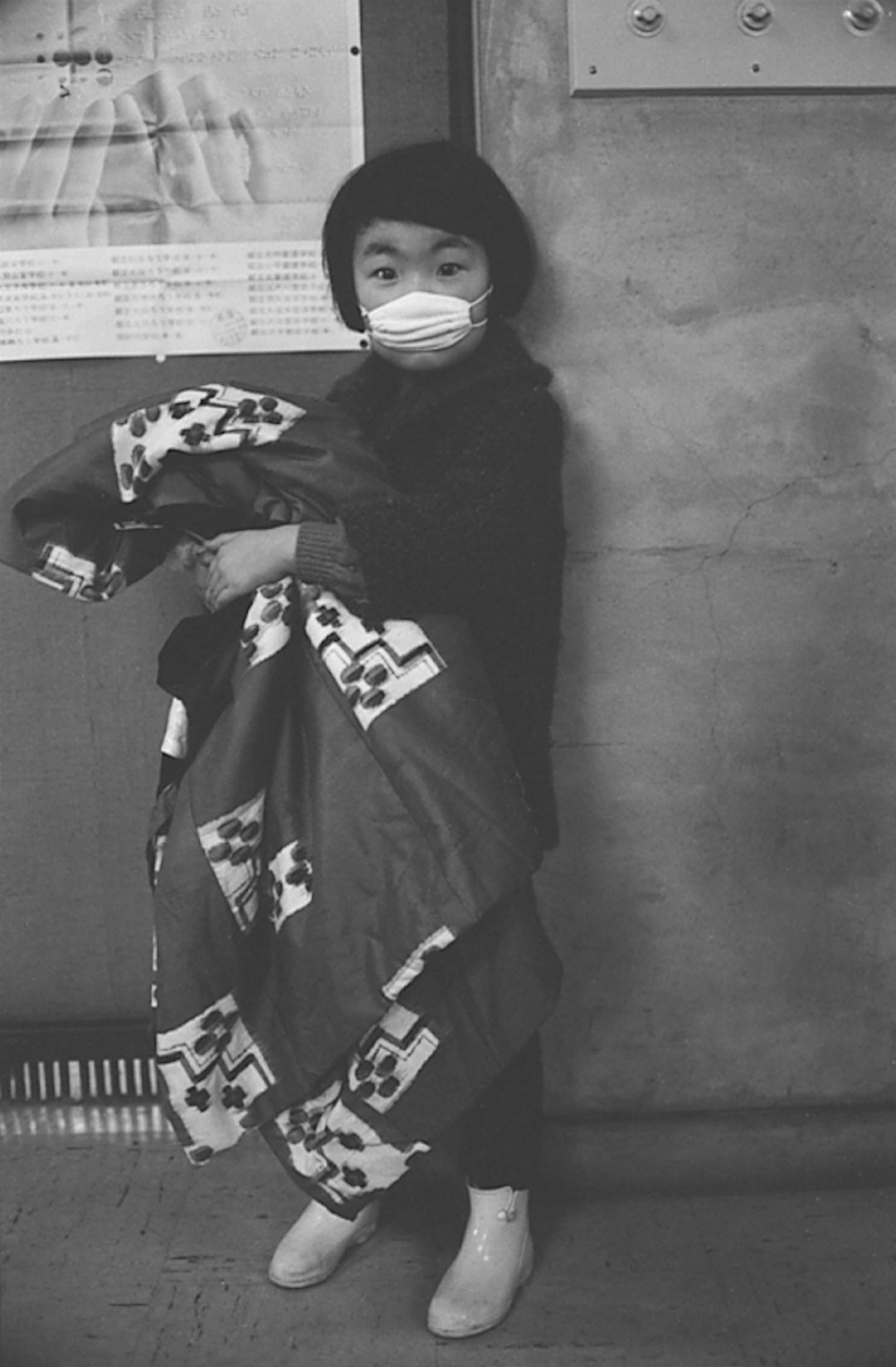

Gradually, the practice of mask-wearing became less dependent on a specific pandemic threat and premised more on an individual duty to protect one’s family, community and country, which demanded sustained engagement. It was not surprising then that public campaigns also built upon themes that integrated family and work life. On the one hand, mask-wearing came to symbolise the love and care in people’s relations with their family members. At the same time, masks became embedded in an employee's contribution to the national economy because it prevented the interruption of work due to sickness.

Credit: WHO/Takeshi Takahara

Children even took masks to school on a weekly basis and there was little need to impose fines on adults to get them to wear masks. Most people did it willingly, often at their own initiative. Millions of masks continued to be manufactured for personal use in Japan, with demand stoked by an emerging culture of mask-wearing being linked with being a good family member, neighbour and citizen.

More from Tetsekela Anyiam-Osigwe

Recommended for you