Rwanda is knocking on every door in a bid to end cervical cancer

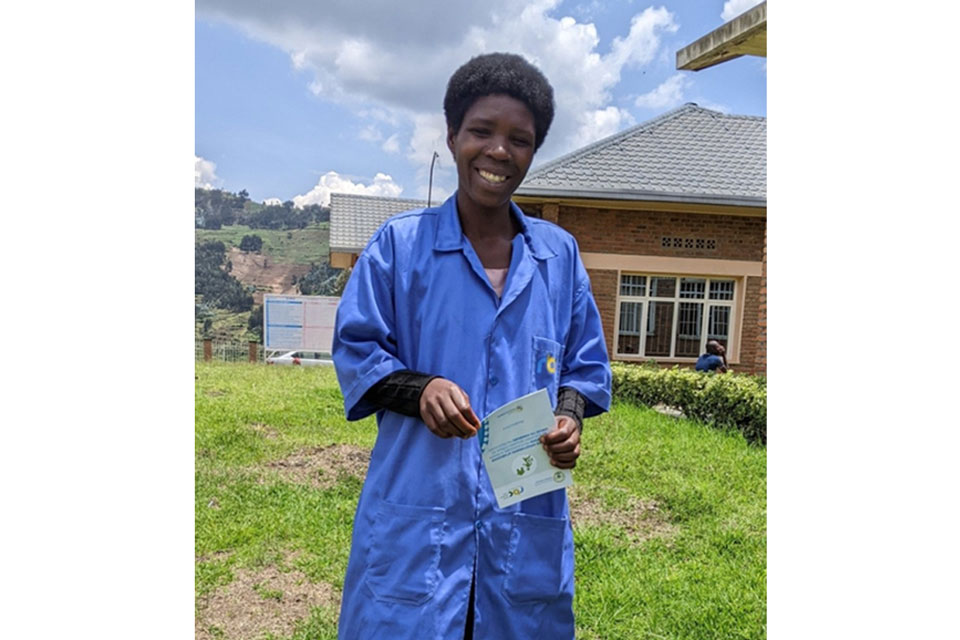

Getting over the cervical cancer elimination line means both vaccinating girls and screening women. Rwanda’s corps of volunteer health workers are going door to door to get it done.

- 6 November 2025

- 5 min read

- by Hudson Kuteesa

In Rwanda, Jean Pierre Bizumuremyi is going door-to-door in a bid to eliminate cervical cancer. There’s a deadline – 2027 – but no specific schedule. “We can go anytime because we are volunteers,” he explains. “Anytime we get time, we just go and do our work as community health workers.”

That work currently focuses on getting every woman aged between 30 and 49 to go and get screened for cervical cancer, and into treatment if she needs it. Districts including Gicumbi, Nyabihu, Rubavu, Karongi, Ngoma, Kicukiro and Bugesera have been covered so far. The plan is to reach every eligible woman across all of Rwanda’s 30 districts by 2027.

In Kicukiro District, Bizumuremyi says he has personally helped some 50 women get screened so far. Visits involve talking to women about cervical cancer, about the importance of early testing, and about the availability of treatment.

Those who agree to be tested receive referrals to the local health centre, where samples are collected to check for human papillomavirus (HPV). If she’s positive, she’s called back again for a clinical examination, to check for lesions.

“Having HPV doesn’t necessarily mean one has cervical cancer,” says Dr Theoneste Maniragaba, Director of the Cancer Programme at Rwanda Biomedical Centre (RBC). Women who are found to have pre-cancerous lesions receive free treatment, often at the health centre level. More advanced cases are referred to higher-level facilities for care.

Early warning

Rachel*, 38, one of the women reached by the campaign in Kicukiro District, Kigali, explains why she decided to go for the screening.

“They told us that if they find signs of cervical cancer, we would start treatment early so it doesn’t develop. That is what motivated me to get tested,” she says.

Two weeks after testing, she received a call to visit the health centre for follow-up, since the medics had identified some concerning signs. Further exams followed, and samples were sent to Butaro Cancer Centre of Excellence in the Northern Province for further scrutiny.

When she spoke to VaccinesWork, she was waiting for her results. She said she thankful for the outreach, admitting that she would not have gone for screening on her own, because she did not feel any pain. “Some people fear testing because they think if they are diagnosed, it is the end. But CHWs are doing a good job explaining that early detection is good, and treatment is available,” she says.

Three-part track to elimination

Dr Maniragaba says the door-to-door campaign methodology was adopted because of “the pressing need” to reach more women in a short period of time.

Rwanda aims to reach the three key World Health Organization (WHO) targets in the fight against cervical cancer – and it aims to reach them in 2027, a full three years ahead of the WHO’s goal-line.

That initiative stipulates that each country achieve 90% HPV vaccine coverage for girls, 70% cervical screening coverage with high-performance tests for women, and treatment for 90% of women diagnosed with cervical pre-cancer or cancer.

Vaccination front-runner

As far as HPV vaccination goes, Rwanda is out ahead. The first African country to introduce a Gavi-supported national HPV vaccination programme in 2011, in 2015 Rwanda transitioned to a routine age-eligibility programme of the sort that is becoming typical across the continent.

Rwanda’s first vaccinated cohort will soon reach their 30s, giving opportunity to health officials to launch research aimed at understanding the vaccine’s long-term impact in regards to shielding them against cervical cancer.

Naomi Ishimwe, now 25 and living in Kigali, recalls being vaccinated in 2012 when she was in Primary 6, in Rusizi, a far-west district.

“At the time, we didn’t know much about the purpose of the vaccine. But now, seeing how women suffer from cervical cancer, I understand that it was for protection,” she says.

Since 2011, coverage has consistently remained above 93%, peaking at 97% in 2019. Rwanda’s first vaccinated cohort will soon reach their 30s, giving opportunity to health officials to launch research aimed at understanding the vaccine’s long-term impact in regards to shielding them against cervical cancer.

Making treatment accessible

Treatment options have also expanded. In partnership with Partners In Health (PIH), an American non-governmental organisation, Rwanda’s Butaro Cancer Centre of Excellence provides chemotherapy and other cancer treatments, free of charge. Patients also receive free meals, accommodation and diagnostic services.

At other cancer treatment facilities, patients with the Community Based Health Insurance (CBHI) pay just 10% of treatment costs, with the insurance covering 90% of procedures including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, surgery and other medicines.

The government approved the policy in January 2025 to ease the financial burden of cancer care.

Have you read?

Odette*, 35, from Musanze, who has undergone treatment for cervical cancer, says that in addition to receiving three rounds of chemotherapy at Butaro, she has benefited from the CBHI as she sought other services including scans.

The last time she went for a scan, she says she paid 29,500 Rwandan francs (approximately US$ 19). She also noted that she paid 3,000 francs (about US$ 2) for morphine and other pills prescribed for her.

A destination, but not a finish-line

There’s progress, in other words, on all three tracks that will converge on the elimination destination. For Bizumuremyi, if Rwanda eliminates cervical cancer, it will be “a major achievement” – not just for the government, but the people.

“Cervical cancer affects people as early as in their 30s. That’s very young. When they become ill or die, the country loses both their lives and the valuable contributions they would have made to its development,” he says.

But he also reiterates the importance of sustaining vaccination and screening programmes even after elimination is achieved, calling upon both the government and the people to continue to play their parts in the fight against cervical cancer.

* Names changed for privacy