Clothing Against Death

In the absence of good vaccines, doctors treating epidemic diseases must rely on cumbersome PPE as their one safety net. At least modern hazmat suits, unlike the 17th century plague doctor's all-leather outfit, actually work.

- 20 August 2021

- 5 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

When the American physician Ian Crozier became infected with Ebola in Sierra Leone in September 2014, he found himself abruptly on the worse side of the hazmat suit. Just a month earlier, he had been making his first rounds wearing the “spacesuit,” adjusting to the way its anonymising form compromised his means of offering care. Now he was sick, shedding lethal virus, and staring up at obscured faces.

Spare a thought for the 17th century’s plague doctor, who wore a stitched, robed, coverall of waxed leather.

“The clinicians taking care of me were in a different type of PPE, but still I could only see their eyes,” he said in a 2015 interview. It was a stark inversion. “I’ve started to talk about this space as a dual citizenship of sorts,” he explained – his identities as Ebola doctor and Ebola patient each assigned distinct provinces by a sealed barrier of protective clothing.

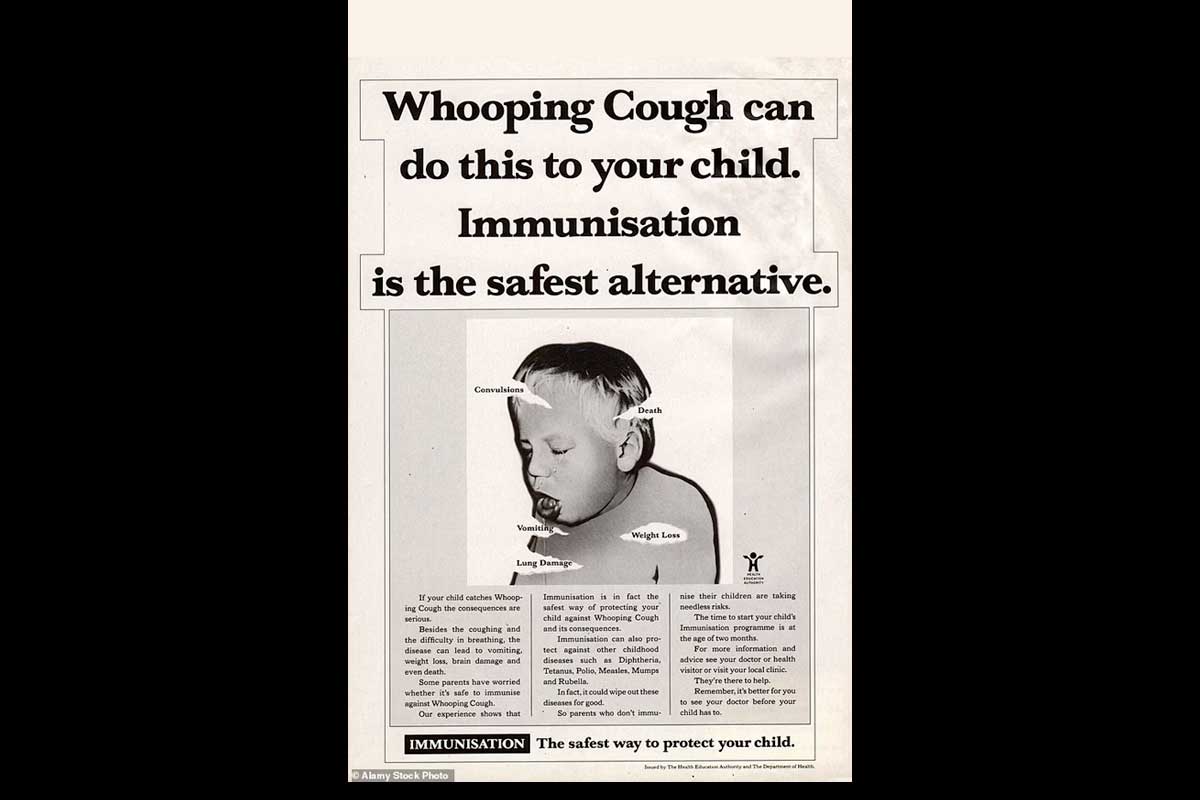

PPE (personal protective equipment, on the off chance you’ve weathered the past year-and-a-half innocent to the acronym) has never been as democratised as it is in our pandemic moment. In supermarkets all over the world, multipacks of medical-grade masks have become checkout display fixtures alongside chewing gum and triple-A batteries. And yet, that all-in, hood-to-rubber-boots variety of PPE – what we think of when we say “hazmat suit” – remains a visual shorthand for the medical frontline.

Illustrations by Elizaveta Mlechkova |

Or, at least, it does during an epidemic. “Hazmat”, a portmanteau for “hazardous material”, can stand for a wide range of perilous stuff. Modern high-tech hazmat suits were conceived for use in the chemical and nuclear sectors, finding their earliest adaptation to medical practice during the Ebola virus outbreaks of the 1990s. Ebola, like Marburg – another deadly filovirus with a recently confirmed case in Guinea – demanded to be handled as carefully as any poison.

Ebola spreads via blood and other bodily fluids, including vomit and faeces, which, in its particularly grisly disease course, are typically in copious evidence; health workers caring for Ebola patients suffering from vomiting, diarrhoea and haemorrhaging are at grave risk of exposure. The job of the hazmat suit is to create a sealed physical frontier – a person-shaped chamber, almost – utterly blocking contact between infected material and the mucous membranes of the eyes, mouth and nose.

Have you read?

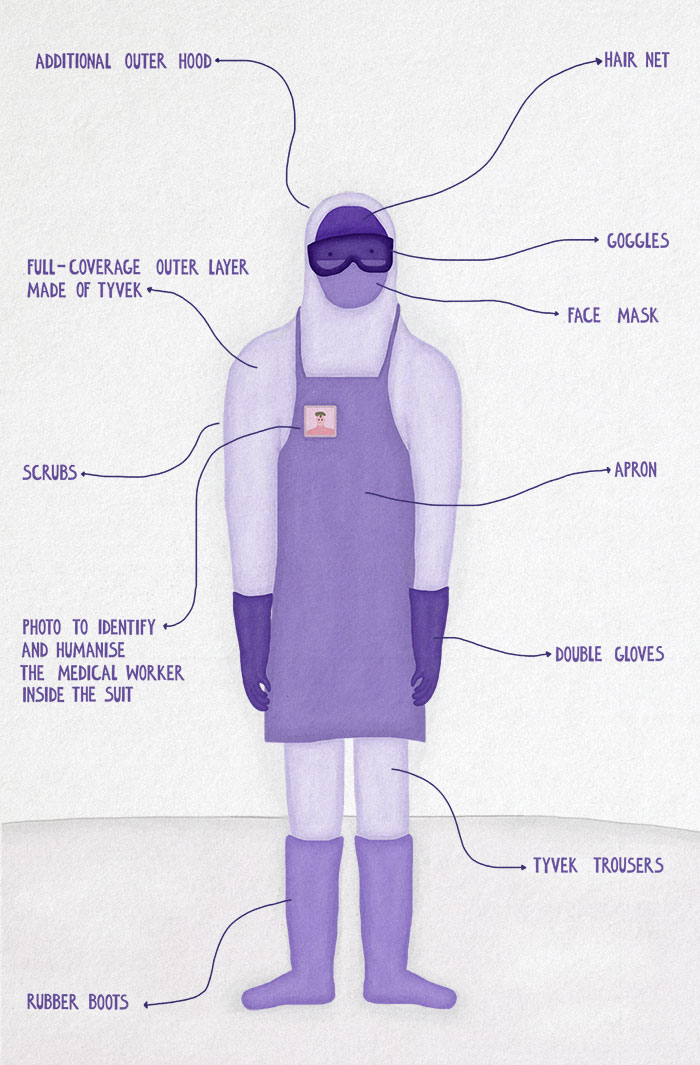

Sealing off a moving, working, human body requires some extravagant layering. A 2016 WHO booklet offering guidance for PPE use during a filovirus disease outbreak recommends a face shield or goggles, a fluid-resistant, structured medical mask (either cup or duckbill-shaped), double gloves (preferably nitrile), a disposable gown and apron, or a disposable coverall and apron, rubber or gum boots, and a separate head cover for both head and neck. The material for the outerwear “must be made of a material that has been tested for resistance to penetration by blood or body fluids or by bloodborne pathogens.” Often, that means Tyvek, an advanced proprietary fabric that feels like paper but is actually a sort of thin, durable, breathable plastic.

Even sheathed in Tyvek, Ebola workers during the 2014-16 West African epidemic rapidly overheated. In an interview with the New York Times, Ian Crozier recalled tipping pooled sweat out of his boots after a session on the isolation ward. More than 500 health staff died during that outbreak, and a further 800 or so others (including Crozier) fell ill. Rather than pointing to an insufficiency in PPE construction, it is thought that a large number of those infections occurred as a consequence of the failure to safely, carefully remove or put on PPE – an easy error in traumatic, understaffed, overworked and desperately hot conditions, and a reminder that for modern medical PPE, the sanitary procedures surrounding the garments constitute an irreplaceable final layer.

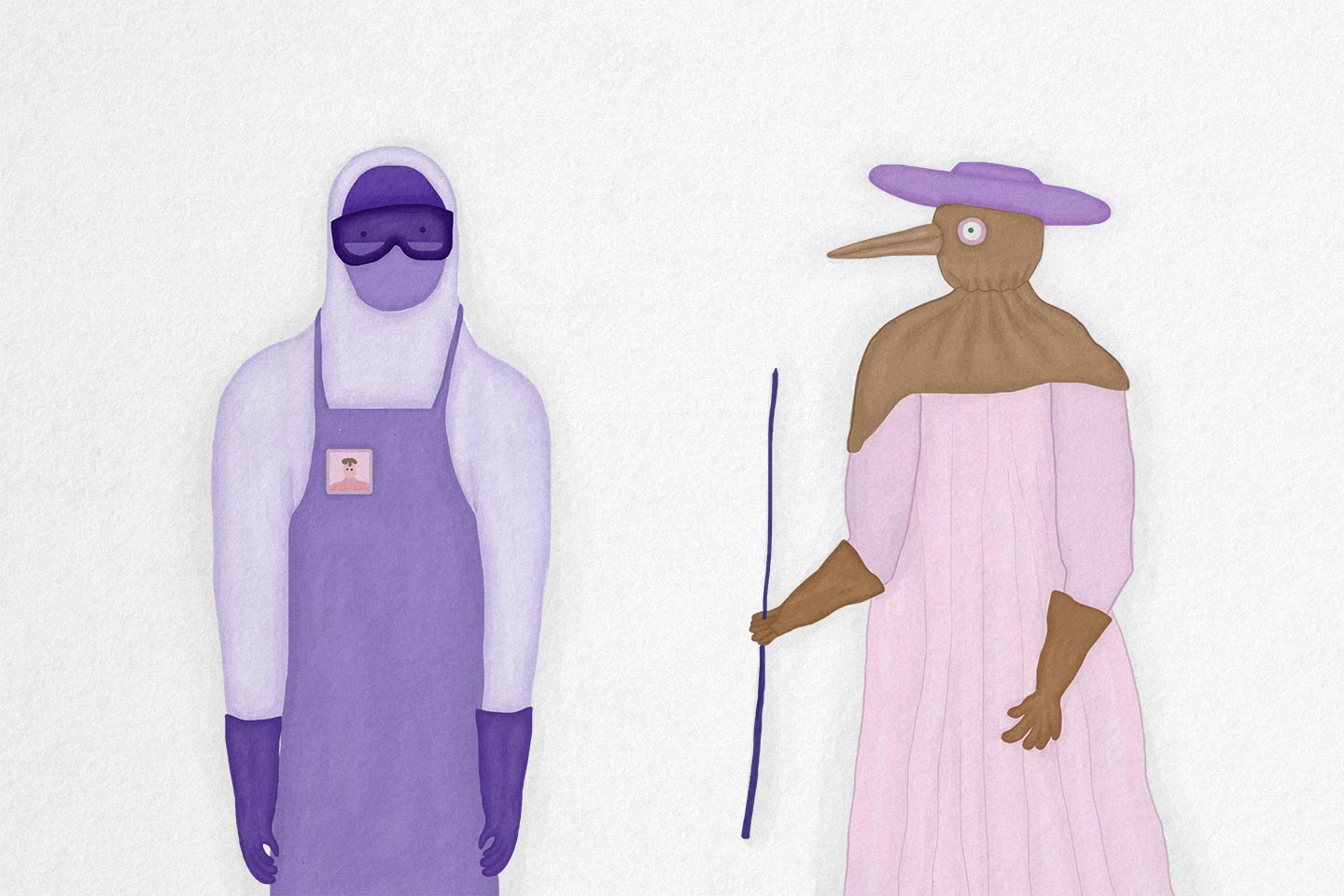

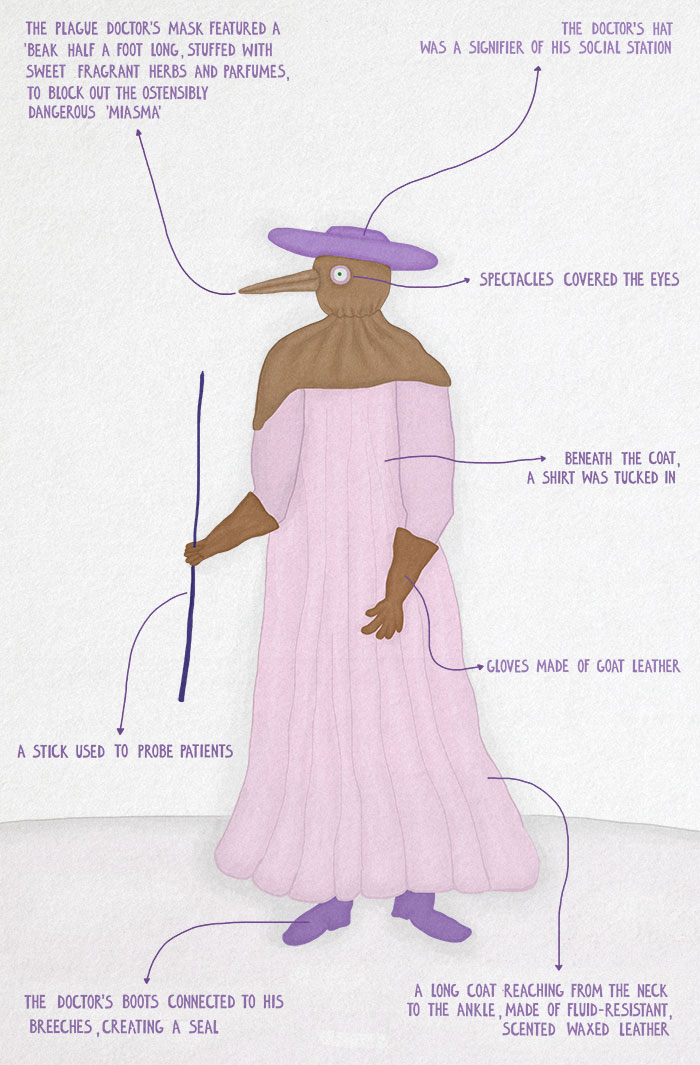

Spare a thought for the 17th century’s plague doctor, who wore a stitched, robed, coverall of waxed leather. ‘Kleidung widder den Todt’, a German engraving of 1656, labels the plague doctors’ garb, iconic today for its beaked mask and flowing robes: “Clothing against death.”

Illustrations by Elizaveta Mlechkova |

Laudable in thought, arguable in fact. “A permanent hazmat suit without removal protocols and disinfectant would be a vector of disease,” as Dr Christos Lynteris of the University of St Andrews explained to the Guardian. Though the “beak-doctor’s” outfit may seem superficially similar (see “crystal glasses”, “breeches connected to the boots” for a seal against contaminants) to modern hazmat gear, any kinship is better described as a case of convergent evolution than heredity.

That’s because the designer of the plague doctor’s PPE was working without any notion of contagion as we understand it. Charles de Lorme, French court doctor, was responding to the 1619 Paris plague which he imagined, pre-germ theory, to be borne and seeded by “miasma” – bad air. That theory explains the outfit’s emblematic, costume-inspiring feature: the half-a-foot-long beak, stuffed with aromatic herbs and perfumes. Where bad odours (inevitable in a deadly epidemic) are imagined to be linked to the disease, good smells might easily be believed to prevent it.

In reality, the plague is spread by Yersinia pestis, a typically flea-borne bacterium, unlikely to be stopped by protective wear. Still, de Lorme’s invention was notable for its radical supposition that clothes might armour our frail bodies against infectious disease.