The malaria vaccine

A VaccinesWork guide: news, science explainers and reported dispatches giving you everything you need to know about the world’s first malaria vaccine and its historic roll-out.

Why do we need a malaria vaccine?

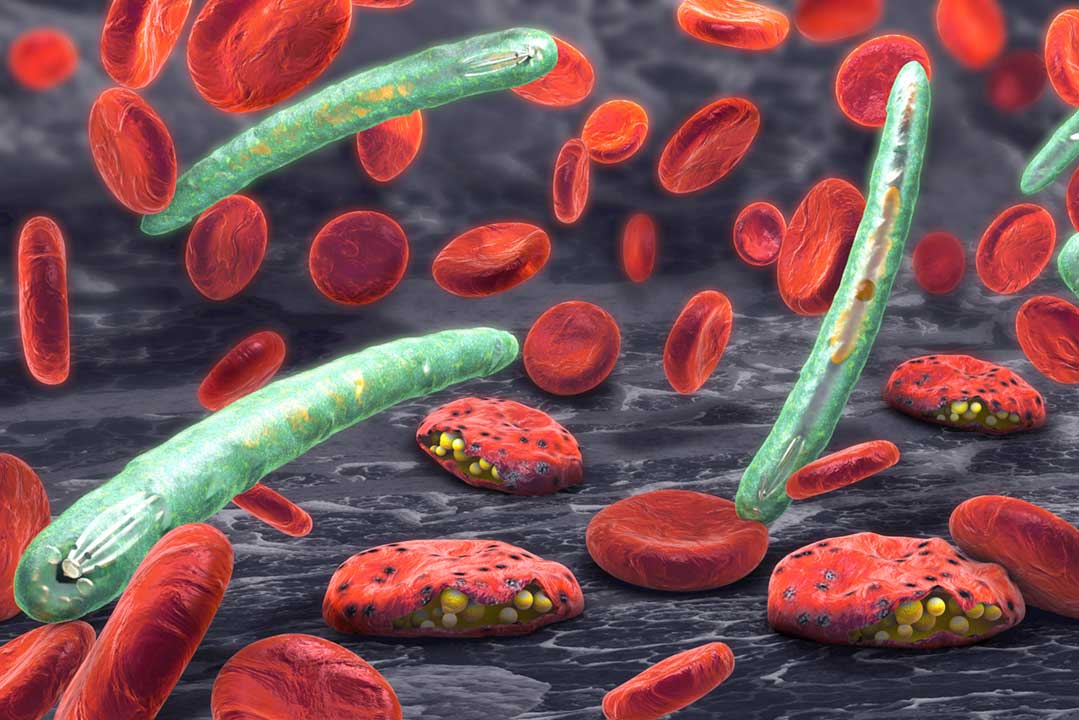

It’s been haunting humanity for millennia, but malaria shows no signs of flagging yet. In 2023 alone, almost 600,000 people died of the mosquito-borne parasitic infection – 95% of them in sub-Saharan Africa. The vast majority of those fatalities occurred in young children.

2023 also saw an estimated 263 million cases of malaria worldwide – 11 million more than 2022. As climate change spurs the spread of vector-borne illnesses, those figures are at risk of rising further.

But now a new tool – touted as a potential game-changer – is being made available to the hardest-hit countries.

The world’s first human vaccine against a parasite, the malaria vaccine is currently rolling out to babies and toddlers, for free, across Africa, with support from Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. Stick with us for news, ground reports, data and analysis from this groundbreaking public health campaign.