Vaccine profiles: malaria

Malaria is on the rise again, fuelled by climate change, but now the world has not one but two vaccines in its arsenal to fight it.

- 23 January 2024

- 5 min read

- by Priya Joi

Malaria is a disease so ancient there are references to it in some of the earliest texts of human civilisation, from Mesopotamian clay tablets in 2000 BCE and Egyptian papyri in 1570 BCE to Chinese documents in 2700 BCE and Hindu texts from the sixth century BCE.

The mosquito-borne disease is endemic in many hot and humid countries, and it is one of the biggest killers in the world, with an estimated 247 million malaria cases and 619,000 malaria deaths globally in 2021. Africa accounts for the vast majority of these cases; the disease is one of the biggest killers of young children under five years of age on the continent, with one child dying every minute.

The road to developing a malaria vaccine has been long – about 30 years in the making – and complicated: targeting a parasite that has a multi-stage life-cycle is complicated. However, after decades of research we now have two vaccines available.

The early symptoms of malaria – headache, fever and chills – may be mild or confused with other illnesses, and so people often aren't diagnosed with malaria until it is too late. Some people recover without treatment, but the disease can be deadly. Untreated, it can cause severe illness or death within 24 hours.

Global killer

Malaria is thought to be responsible for up to five percent of all human deaths in the 20th Century. According to the latest World Health Organization (WHO) World Malaria Report, there were 249 million cases of malaria in 2022 compared to 244 million cases in 2021. The estimated number of malaria deaths stood at 608,000 in 2022 compared to 610,000 in 2021.

After decades of progress in fighting malaria, the last decade or so has seen this progress slow. Between 2000 and 2015 the global death toll fell by almost 40%: from 896,000 deaths in 2000 to 562,000 in 2015. After this, however, numbers began to rise. In 2020, malaria deaths increased by 10% compared with 2019 to 625,000; although this has fallen again, it's still higher than in 2015.

Most of the global malaria burden is in Africa, which had 94% of all malaria cases and 95% of deaths in 2022. The disease affects young children disproportionately, and 78% of malaria deaths in Africa are in children younger than five years.

However, the disease has only been concentrated in Africa relatively recently in its history; until the mid-20th century, it was far more global: it was only eliminated from Spain in 1964 and from Italy in 1970.

Climate change could reverse that, however, as global warming has already caused significant changes in the way malaria is spreading and will greatly expand the number of people at risk. Flooding, increased rainfall and the warming of once-temperate regions means that malaria-carrying mosquitoes are able to inhabit new parts of the world.

Vaccine development

The road to developing a malaria vaccine has been long – about 30 years in the making – and complicated: targeting a parasite that has a multi-stage life-cycle is complicated. However, after decades of research we now have two vaccines available. In 2021 the RTS,S vaccine was approved, or 'prequalified', by WHO and two years later the R21 vaccine was approved; both target the sporozoite of the malaria parasite.

Have you read?

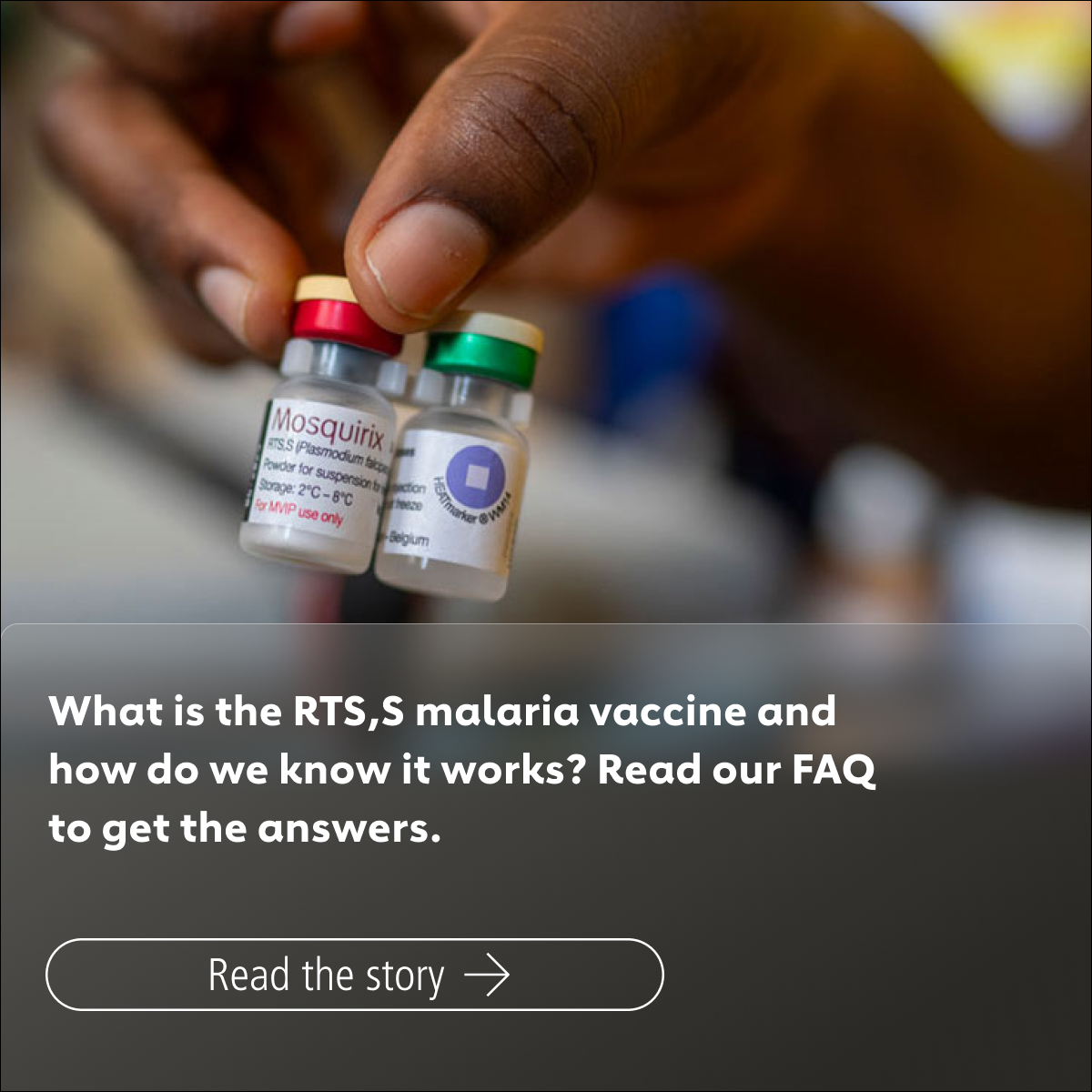

The RTS,S vaccine has been tested in rigorous clinical trials, and was shown to be effective in children with HIV and malnutrition, an important consideration for its use in young children in Africa.

In 2019, the Malaria Vaccine Implementation Programme (MVIP), coordinated by WHO and funded by Gavi, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, and Unitaid, began large-scale pilots to evaluate the public health use of the RTS,S vaccine in Ghana, Kenya and Malawi.

As of the end of September 2023, more than four years since the start of vaccinations, 5.8 million RTS,S vaccine doses had been administered and nearly two million children at risk had been reached with the malaria vaccine across the three pilot countries.

The RTS,S malaria vaccine implementation has resulted in a substantial fall in severe malaria hospitalisations, and a significant drop in child deaths – there was a 13% drop in all-cause mortality (i.e. not just from malaria) in the areas where the vaccine was piloted.

Vaccine rollout

Gavi is supporting the introduction of malaria vaccines to eligible countries. In July 2023, 18 million doses of RTS,S available for 2023–2025 were allocated to 12 countries, prioritising those doses to areas of highest need, where the risk of malaria illness and death among children is highest, until vaccine supply increases to fully meet demand.

In January 2024, Cameroon became the first country to introduce the first shipment of 331,200 doses of RTS,S vaccine. Demand for the malaria vaccines is significant – 20 countries in Africa plan to introduce the malaria vaccine into their childhood immunisation programmes in 2024 alone. Annually, at least 40–60 million doses of malaria vaccine will be needed by 2026, growing to 80–100 million doses each year by 2030.

R21 has not yet been rolled out widely, although in areas where malaria transmission is highly seasonal (limited to four to five months per year), the R21 vaccine reduced malaria cases by 75%. According to WHO, "This high efficacy is similar to the efficacy demonstrated when RTS,S is given seasonally."

The fact that there are now two effective vaccines to use alongside other proven interventions like insecticide-treated bednets, should ensure significant progress in working towards malaria elimination.