The mesquite and the mosquito: Malaria threat spreads in Kenya's Rift Valley

How mathenge, a thorny invasive plant colonising large tracts of Kenya, is fuelling malaria transmission, even in semi-arid landscapes.

- 31 August 2023

- 9 min read

- by Kang-Chun Cheng

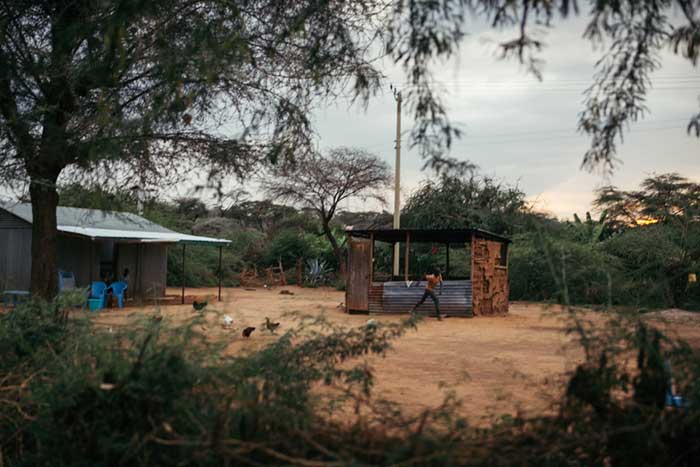

Baringo County, in the central-western portion of Kenya's Great Rift Valley, is classed as a semi-arid landscape. Though seasonal rivers traverse the region's rocky valleys, and wetlands dot the plains, the landscape is dominated by savannahs.

But even here, the risk of malaria, an infectious disease commonly associated with wet places, persists.

Around those scattered marshy areas, teeming mosquitoes are not only a nuisance, but a menace to public health. And their threat has worsened in recent years because of the encroachment of one thorny invasive tree.

"We can’t control how mathenge grows along a wetland of this size"

– Peter Lembes, Kapkuikui herder and farmer

Known as mathenge in Kiswahili, Prosopis juliflora is a species of mesquite native to South America. It was intentionally introduced around 1984 by the World Bank and the UN's Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) to 'rehabilitate' dry plains across Kenya by providing the ecosystem service of shade and clean water.

But it has proven difficult to keep in check. "We can't control how mathenge grows along a wetland of this size," says 36-year-old Peter Lembes from Kapkuikui, a village of 6,000 people that teeters on the edge of Kiborgoch Community Wildlife and Wetland Conservancy.

Credit: Kang-Chun Cheng

Credit: Kang-Chun Cheng

Kapkuikui is just one of many under-resourced settlements adjacent to Kiborgoch – communities facing the troubling impacts of drought and environmental degradation on livelihoods. Most of Kapkuikui's people live on irrigation agriculture and herding, for which they must compete for space with Kiborgoch's wild inhabitants: zebras, roebuck, ostriches, and many other species.

Their biggest rival, however, might be the feral mathenge. Although it thrives in harsh conditions, mathenge is particularly robust in wet areas. People have tried cutting mathenge down – a manageable task when confined to private lands. But here, at this scale, containment is unmanageable.

The invasive plant threatens the health of the landscape – in both Ethiopia and Kenya, it outcompetes local flora, with one study finding that in places where mathenge has proliferated, occurrence of the indigenous Acacia tortilis tree dropped from 81% in 1990 to 43% in 2007.

It also threatens human health, and not just by imperilling food production.

Mathenge and malaria: an "unholy union"

The shrubby trees provide shade in an otherwise sweltering environment – creating conditions that are better suited for the growth and maturation for mosquito larvae. Streams and irrigation canals, built a few decades ago to support the region's growing populations, also serve as hotspots for mosquitoes to breed.

Indeed, Kapkuikui residents claim that there have been more mosquitoes – which transmit diseases like malaria and dengue – around over the last 20 years, and the majority of individuals that VaccinesWork interviewed reported having suffered at least one bout of malaria.

Credit: Kang-Chun Cheng

Credit: Kang-Chun Cheng

Credit: Kang-Chun Cheng

Staline Kibet, a botanist at the University of Nairobi, described mathenge and malaria as an "unholy union" in an email to VaccinesWork.

"Mathenge increases mosquito proliferation, and is also connected to land degradation," says Tobias Landmann, a geosurface engineer at the International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology (ICPE) in Nairobi.

“Mathenge has come to signal general sickness and ill health for humans and animals alike. I doubt people care much about water quality when their livestock are sick and the farms are strangled.””

– Samuel Derbyshire, International Livestock Research Institute

Landmann researches the propagation of invasive plants using satellite imagery and modelling. "It's a chain," he tells VaccinesWork. "The propagation of invasive plants or woody vegetation will completely change vector ecology."

At the same time, mathenge physically obstructs the movement of herders and their grazing animals. "Framing it in the context of invasive plants in general, it's one of the most devastating weeds for rangelands and farmers. It makes the soil unusable," Landmann explains.

Changing lifestyles, rising risk

The effects are evident in Kapkuikui. Not only are residents slapping more bugs and catching more fevers, but their ways of life are shifting.

Lembes, like most other members of his community, mainly keeps livestock for a living – goats and some cows. He also has a modest shamba where he farms maize, beans, and tomatoes for his family.

Increasingly, traditionally pastoralist communities in Baringo are diversifying their livelihoods by farming crops and keeping bees. It's not a coincidence that this diversification follows the spread of mathenge, which now chokes large tracts of ancestral grazing lands.

There are other drivers for these shifts. As climate change increases the severity of droughts, and communities settle close to water sources such as Kiborgoch, new opportunities for farming and beekeeping present themselves. Baringo has, in recent years, become a major honey producer.

But the same areas that are drawing people are attractive to mathenge – which continues to spread, creating ever more breeding spots for mosquitoes, fuelling the risk of malaria.

A thorny business

Still, Cyprian Odoli, a principal researcher and station manager at the Kenya Forestry Research Institute (KEFRI) in Baringo, thinks the criticism of mathenge – which the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists as one of the 100 worst invasive species in the world – has been too harsh.

"Mathenge has been debated with constant dilemma…but research has majorly focused on its impacts on livelihood and economy to the community members, with [a] knowledge gap on its impacts on water quality," Odoli writes in an email interview. "Lake Baringo [one of the Rift Valley Lakes] has recorded continuous improvement in water quality, specifically reducing water turbidity since the 1990s to date."

Have you read?

Some Baringo residents echo Odoli's efforts to find the good in the troublesome invader. "It's evergreen, even during droughts," says Simon Chesang, another resident of Kapkuikui village, adding that mathenge acts as an efficient wind-breaker and mitigates dust storms.

Credit: Kang-Chun Cheng

Credit: Kang-Chun Cheng

As a honey producer, he values the fact that its year-round flowers make keeping bee hives easier.

Margaret Bartai, a Kapkuikui seamstress, has only good things to say about the thorny tree. "It's a very smart plant," she repeats. "I make jiko (charcoal) from the wood, grind up the pods to feed my goats, and it also makes for good fencing."

Since the early 2000s, the Ministry of Health has been hosting community sensitisation workshops in Marigat, the town just west of Kapkuikui, to encourage communities to find ways to benefit from mathenge. "There are a few benefits," Landmann admits. "Prosopis does build resilience for climate shocks by managing erosion, and can be made into charcoal. So it's not a total loss."

Credit: Kang-Chun Cheng

"Where it grows, nothing else can survive"

But for farmers and pastoralists, it's hard to see past its destructive character. "We call it a weed," says Chesang finally, standing in his front yard, where chickens are pecking hopefully. As well as producing honey, Chesang farms and keeps livestock to support his family of five. "Where it grows, nothing else can survive next to it," he continues. "Natural trees die and no grass grows beneath."

Its thorns don't decompose, instead staying in the landscape "like a nail", in Chesang's words – wounding animals and humans alike.

Samuel Derbyshire, an anthropologist specialising in East African pastoralism and a drought researcher at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) in Nairobi, sees the plant's scant benefits as dwarfed by its hazards. "Mathenge has come to signal general sickness and ill health for humans and animals alike," he tells VaccinesWork. "I doubt people care much about water quality when their livestock are sick and the farms are strangled."

With its high sugar content, mathenge wreaks dental damage on Baringo's goats and cows. "Their teeth fall out and they starve to death," Chesang says. " I've opened up the stomachs of cows who died from what I suspected was eating mathenge and not being able to digest it. Instead of being rough, their stomachs were smooth. I'm just a farmer, but I suspect that something about mathenge is bad for ruminants." He estimates that over the past three years, he's lost about 40 goats to mathenge.

And if the economic threat isn't grave enough, there's the mosquito-borne one too. Research has found that invasive plants that provide critical sources of sugar – particularly during dry seasons – contribute to malaria vector survival by essentially lengthening transmission seasons.

Credit: Kang-Chun Cheng

Forecast: malaria

While the Kenya Meteorological Department has found that many Rift Valley regions remain drier than average, large parts of Kenya and the greater Horn of Africa are coming to the end of a punishing three year drought. That means rain is forecast – and with it, in all likelihood, a surge of illness.

Kuto Chilumo, a medical parasitologist researcher stationed in Marigat, says that the connection between rainy seasons and malaria transmission rates is undeniable: infections always follow the arrival of wet weather.

Chilumo works for a government research lab, part of the Ministry of Health. The lab was founded to address neglected tropical diseases – intended to monitor changes in the diseases plaguing local communities, Chilumo explains. But when Kenya's government structure devolved around 2012, funding dried up.

"Mathenge increases mosquito proliferation, and is also connected to land degradation."

– Tobias Landmann, International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology

"Electricity was cut from the lab last week, and generally we suffer from little to no funding by the county government." The Marigat lab has an air of abandonment. Thugs had broken in the night before our interview, he said, but there wasn't much for them to take.

"Yet malaria remains a top concern in this area." A malaria-bearing mosquito can infect multiple people, Chilumo explains. "When there's an infectious female, the probability of multiple members of the household getting infected is high."

Credit: Kang-Chun Cheng

Marigat is becoming an increasingly cosmopolitan town, a hub connecting largely pastoral Baringo to counties like Nakuru and Kisumu. "People travel here or pass through Kisumu, and can pass on parasites picked up along the way," says Chilumo.

Rose Rerimoi is a nurse at the government-funded Kapkuikui dispensary. Her days are packed with testing for illnesses like malaria, typhoid, and HIV. From her work at the clinic, she sees malaria persisting as a major disease – one linked to poor water quality and exacerbated by a lack of equitable healthcare access.

Credit: Kang-Chun Cheng

Although mosquito net distribution programs are stabilising malaria flare-ups, she says that there are issues with the reliable reissuing of nets– which tend to wear out after a couple of years – and convincing community members to use them correctly. "It's not uncommon to see people use nets for covering their shambas," Rerimoi observes.

Supply concerns seem to have calmed over the course of the past decade, thanks to efforts by the Ministry of Health to distribute sleeping nets and stock dispensaries with malaria rapid test kits and chemoprophylactic medicines. Yet the root of the problem – the prevalence of vector-carrying mosquitoes – persists. "After the offset of the long rains, you will be sure there will be many malaria cases for residents here," Rerimoi says.