Modelling suggests suppression strategy will save more lives from COVID-19 in poor countries

Imperial model of the spread of COVID-19 implies a suppression strategy could be most effective.

- 1 April 2020

- 7 min read

- by Priya Joi

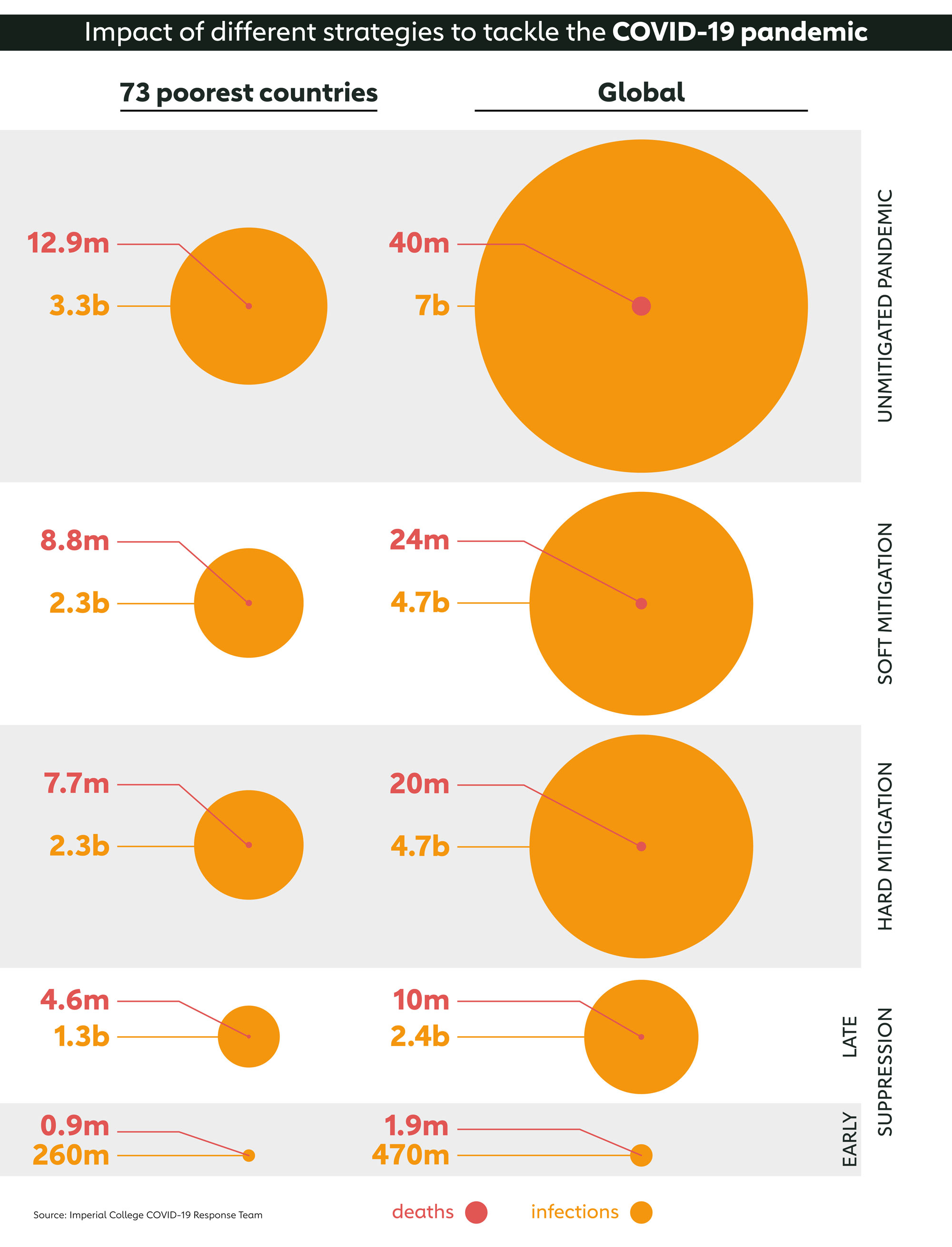

If no action was taken to reduce the spread of COVID-19, as many as 7 billion people could become infected by the end of the year, with 40 million of them dying. In the world’s 73 poorest countries, that would translate to 3.3 billion cases and 12.9 million deaths, not including any additional deaths resulting from disruption to critical health services, like immunisation programmes. That’s according to analysis carried out by a team of researchers at Imperial College in London, whose modelling work has already helped influence COVID-19 policy in the UK and elsewhere.

This is of course is only one potential worst-case scenario, since governments across the globe have introduced a wide range of measures to try to tackle the pandemic. But how will these play out in different settings? In the same analysis the Imperial team have looked at different strategies to find out.

By comparing strategies like “mitigation” and “suppression”, as well as the degrees to which they are used and the timing, the researchers found that the global number of cases could be reduced to 470 million, with 1.9 million deaths. When broken down by region, roughly half of these cases and deaths would be in the 73 poorest countries, those supported by Gavi. This represents a higher proportion of the total than if no measures were taken, meaning that while many lives can be saved using these strategies, they are likely to be less effective in poorer countries.

So, what are these strategies?

Mitigation

With mitigation, in the absence of any effective drugs or vaccine, the aim is to try to delay the spread of the virus to reduce its impact on health systems. The basic assumption is that if the virus is already circulating widely, then preventing its spread will be next to impossible. And if a large part of the population does become infected at the same time, the risk is that a surge in the number of cases will create a peak demand that will overwhelm health services.

But by delaying the spread, the peak can be reduced and spread out over a longer period of time, reducing the peak burden on healthcare systems. Known as “flattening the curve” such mitigation approaches can involve a wide range of measures, from closing schools and universities, and encouraging people to work from home if they can, to isolating people who are infected or most at risk and encouraging physical distancing practices. Essentially mitigation attempts to slow the outbreak rather than stop it.

Flattening the curve may reduce the burden on health systems, as well as societal and economic disruption, but it doesn’t mean that health systems won’t still end up being overwhelmed. However, in the medium to long-term, the mitigation approach should allow a population to build up herd immunity to COVID-19, allowing it to resume normal activities with minimal risk of a resurgence in disease because the virus will no longer be able to continuously find susceptible people to infect.

Suppression

Suppression also attempts to flatten the curve, but rather than just spread it over time the objective is to actually stop the virus from spreading to quash the outbreak. This can involve using similar measures as mitigation, but in a more heavy-handed way, such as tighter restrictions on travel or mandatory home lockdowns and self-isolation.

Described by some as the hammer approach, while suppression may potentially lead to fewer people becoming infected, and so fewer deaths, it comes at a cost. The disruption of effectively shutting a country down for several months during a prolonged lockdown could have a hugely negative impact on the economy.

Compared to mitigation, it also risks failure. People’s tolerance for being in lockdown for long periods of time can wane and lead to some flouting the rules and undermining the efforts. And unless the virus is completely extinguished, not just in that country but neighbouring ones too, there is always a risk of resurgence once the lockdown is over.

Which strategies are most effective?

In their analysis the Imperial team compared four different strategies against the worst-case scenario. The first, involving a mitigation strategy where the whole population is encouraged to practice physical distancing, found that global infections could be reduced to 4.7 billion people, and deaths to 24 million. In the world’s 73 poorest countries, those supported by Gavi, infections would drop from 3.3 billion to 2.3 billion, and deaths from 12.9 million to 8.8 million.

In contrast a slightly more stringent mitigation approach, which involved the same measures, but with enhanced physical distancing of older people, resulted in the same number of people being infected, but four million more lives being saved globally, and a million more in poor countries.

A suppression approach was found to be more effective, but more dependent on timing. If suppression was only introduced once the number of deaths exceeded 1.6 per million per week, the number of infected could drop to 2.4 billion and deaths to 10 million, a quarter of that if no action was taken. In low-income settings the number of cases would fall by a similar proportion to 1.3 billion, but deaths would only drop to about a third with 4.6 million.

If suppression were introduced sooner, however, when there were 0.2 deaths per million per week, the impact would be significantly greater. Globally, the number of cases would drop to 0.47 billion, a 93% reduction compared to if no action was taken, and deaths would fall to 1.9 million, a reduction of more than 95%. In poor countries the drop in the number of infected would be commensurate with the global, falling to 0.26 billion. But deaths would fall by about 93% to 0.9 million, a considerably lower reduction than the global average.

How reliable are these models?

Like any kind of modelling, many assumptions were made with this analysis. For example, it assumes that hospital capacity does not vary across countries when projecting expected deaths. Given that hospital capacity is usually much lower in low-income countries, a higher proportion of severe cases are likely to result in death.

Another assumption is that regions like sub-Saharan Africa may have a lower case fatality rate because just 4.8% of the population is over 60-years-old, compared to 29.9% in Italy and 17.3% in China. Since over-60s are more likely to die, on paper this may mean that the region could see proportionally fewer deaths. However, the analysis did not take into account the effect of other risk factors for COVID-19 mortality besides age. If malnutrition or infection with HIV turn out to increase the risk of dying for people infected with COVID-19, the overall case fatality rate in regions like sub-Saharan Africa could be higher.

So, while the accuracy of this model should be viewed with caution, as with any model, many of the assumptions made make its findings relatively cautious. Also, given that many low-income countries have weak health systems, the feasibility of implementing mitigation or suppression strategies as effectively as wealthier countries is doubtful. Physical distancing, for example, can be impractical when you may have three generations living in a crowded home in a slum or when people living hand-to-mouth need to continue working close to people to survive. Similarly, limited access to clean water can make regular hand-washing less feasible for hundreds of millions of people.

Another important issue is that none of this analysis factors in the indirect non-COVID-19-related deaths, such as those resulting from the additional pressure placed on health services by the pandemic, such as the cessation of immunisation programmes. These are likely to push the number of deaths higher. So while early suppression seems like the most effective strategy, it will be particularly important to support low-income countries, not just in reducing the spread of this pandemic, but also in bolstering their health systems and ensuring that efforts to tackle COVID-19 don’t come at the expense of other health concerns.