Vaccine profiles: mpox

The virus has surged in recent years, causing public health emergencies in 2022 and 2024.

- 30 August 2024

- 5 min read

- by Gavi Staff

Factfile: mpox

- Type: Virus

- Symptoms: Fever, headache, muscle ache, swollen lymph nodes, chills and exhaustion, followed by a rash on the face, hands and feet, that can spread to the inside of the mouth, the genitals and the cornea.

- Mortality rate: Up to 10% depending on the strain

- Annual cases and deaths: Highly variable dependent on outbreaks

- Geographical range: Mostly West and Central Africa, although 2022 saw a global outbreak in 111 countries.

Since the early 2000s, African epidemiologists have been growing more concerned about shifting patterns of transmission of mpox (formerly monkeypox), endemic in West and Central Africa. The virus circulating in these regions is deadly – it can kill up to one in ten people.

In 2017, Nigeria saw a re-emergence of cases after nearly four decades of zero cases; not just that, the disease was spreading in an unusual way. Most patients were young men who had lesions or skin rashes and ulcers around the genital area – which told scientists for the first time that mpox might also be spread through sexual contact. By this point, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) had also seen cases steadily rising.

Global outbreaks

In May 2022, a case of mpox was detected in the UK, and soon several more – apparently unconnected – cases were found, spreading across borders in Europe and to the US. There are two groups or 'clades'; with clade I infections being more deadly - one in ten cases can be fatal. This outbreak was caused by the clade II strain.

Nonetheless, this outbreak was unprecedented. Scientists puzzled over how a disease that wasn't thought to be easily transmissible was spreading so widely in non-endemic countries.

It soon emerged that most of the cases across Europe and the US were in men who have sex with men, especially those who had closely connected sexual networks, allowing the virus to spread in a way it hadn't in the general population.

By July 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the global outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC), a move intended to galvanise action to respond to the emergency.

By the time WHO declared the end of the PHEIC in May 2023, more than 87,000 cases and 140 deaths had been reported from 111 countries.

Unfortunately, this was not the end of mpox’s resurgence. Just over a year later, on 14 August 2024, WHO declared once more that mpox was a PHEIC after Africa. This declaration was prompted by a surge of mpox cases in countries like DRC, but also in neighbouring countries that had never seen mpox before, such as Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda and Uganda. And this time it was being caused by the more deadly clade I strain.

History of the virus

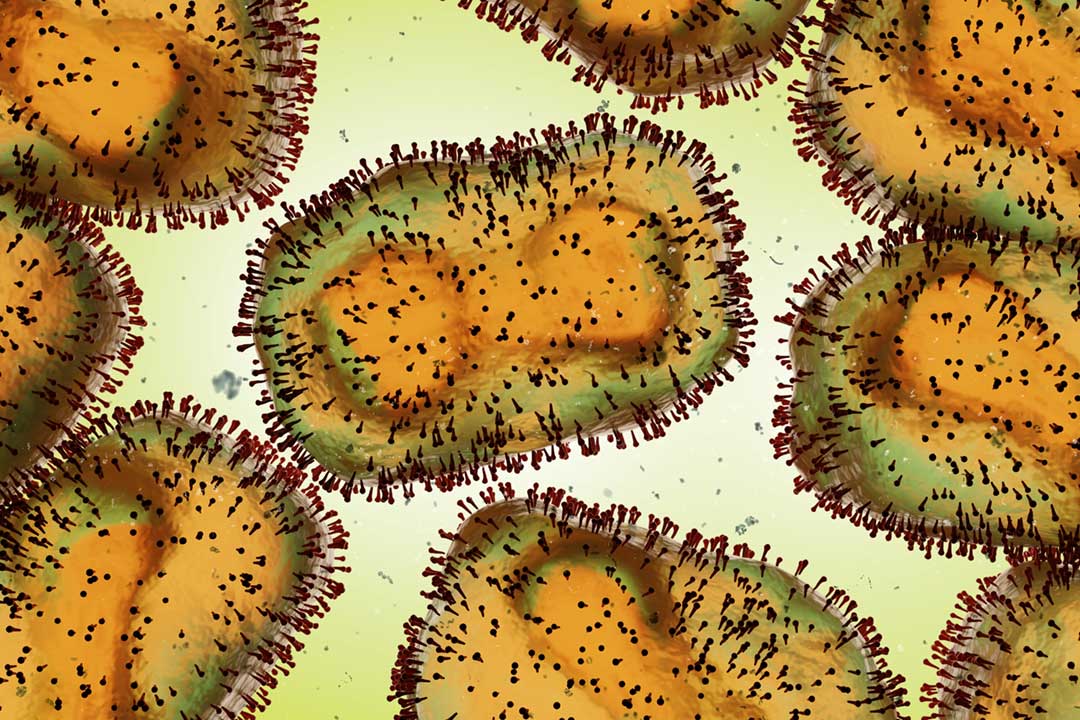

Mpox and smallpox are members of the Orthopoxvirus genus in the family Poxviridae. Mpox was first discovered in 1958 when outbreaks of a disease that caused pox-like symptoms were discovered in monkeys held in captivity for research. It was first seen in humans in 1970 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and it is now endemic in Central and West Africa.

People can get infected either through contact with animals – for example via infected rodents through broken skin (bites or scratches), or direct contact with an infected animal's blood, bodily fluids or pox lesions (sores). The virus can also spread between people, through skin-to-skin contact with sores, scabs, respiratory droplets or oral fluids, usually through close, intimate situations, and much of the recent spike in cases has been through sexual transmission.

Early symptoms include fever, headache, muscle ache, backache, swollen lymph nodes, chills and exhaustion. Once a fever has appeared, a rash tends to follow, mostly on the face, hands and feet before spreading to other areas of the body. It can spread to the inside of the mouth, the genitals and the cornea.

The rash progresses until it forms a scab which falls off, and in some cases large sections of skin can drop off the body. Symptoms normally appear between five and 13 days after infection, although it can take up to 21 days for them to appear.

Mpox vaccines

Mpox is closely related to smallpox, and the smallpox vaccine that can prevent about 85% of mpox cases have been deployed in recent emergencies to curb transmission.

Two mpox vaccines, Jynneos (Bavarian Nordic) and ACAM2000 (Emergent Biosolutions), have been licensed in the US, with Jynneos also licensed in Canada and Europe. Jynneos has been approved for people older than 18, while ACAM2000 has also been approved for paediatric populations. LC16m8, an attenuated, replicating smallpox vaccine is currently licensed in Japan for both children and adults. However, it's not clear yet how long immunity lasts. At present, WHO recommends use of MVA-BN or LC16 vaccines, or the ACAM2000 vaccine when the others are not available.

BioNTech, in partnership with CEPI (Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations) started a Phase 1/2 clinical trial of the mRNA-based mpox vaccine candidate, BNT166, due to be completed in May 2025.

Have you read?

Closer scrutiny needed

As African scientists have flagged, poor surveillance and diagnosis meant that the virus became a global threat under little scrutiny. Now that the mpox genome is being investigated for mutations, scientists have been able to detect specific genetic changes that have allowed the virus to spread more easily.

This work will be crucial to answer other questions: what is the incubation period of the virus in the body? Can the virus spread through airborne transmission? When people are infected and recover, are they immune from future infections?

And researchers from the continent most affected should be in the driving seat, says Nigerian scientist Dr Adesola Yinka-Ogunleye, at the Institute of Global Health, UCL, London, UK, who provided technical expertise to WHO during the 2022 outbreak. She told Gavi: “the most important lesson for me is the urgent need for African researchers to do more and be empowered to contribute to the knowledge of the diseases that plague the continent.”

This article was originally published on 10 October 2023.