Tanzania’s newly trained 'army' of community health workers

The country aims to train and equip nearly 140,000 frontliners by 2028, in what leaders hope represents a transformative shift for healthcare at the grassroots.

- 24 November 2025

- 5 min read

- by Syriacus Buguzi

Chiku Abdallah, a community health worker (CHW) from Mtundilikile village in Tanzania’s Lindi region, remembers a time when providing health education to her community members in her village felt like reciting facts without having a clear understanding of what she was sharing.

“I had no formal training,” the 20-year-old says. “I used to warn people about disease outbreaks but I knew little on how to protect myself and what that meant for my community. I also used not to understand the impact of teenage pregnancies – for example, I never knew there was a link between teenage pregnancy and death [rates]."

Today, armed with a digital tablet and improved know-how, Abdallah feels less like a volunteer anymore, and more like a professional. “I know even how to protect myself and the community surrounding me.”

Abdallah is one of 3,600 CHWs who have just completed the rigorous, six-month Integrated and Coordinated Community Health Workers Programme, an initiative launched in 2024 by Tanzania’s Ministry of Health in collaboration with the President’s Office-Regional Administration, local government and partners.

Hers is the first cohort to have been formally trained, equipped and re-deployed under the programme, which aims to both professionalise and expand the community health workforce. By 2028, the government expects to be able to deploy 137,294 CHWs in 4,263 mitaa and 64,384 hamlets across Tanzania.

Marburg was a warning

A Marburg virus outbreak in the Kagera region in January to March 2025 was a key turning point for CHW policy in Tanzania.

Dr Norman Jonas, a medical specialist and National Coordinator for the Community-Based Health Services Program of the Ministry of Health, says: “The Marburg virus is difficult to contain, and it requires a successful, rapid response tied on a key factor: early detection by a community based worker.”

He credits the Kagera Region CHWs who first raised the alarm about the suspicious cluster of cases, but says with more training and resources – standardised tools, an integrated reporting structure, for instance – they could have done more. “This cadre of health workers has untapped potential for improving health at grassroots level.”

“We faced challenges with community health workers who were not trained,” says Kitenge Seleman, Ward Executive for Kitengule in Lindi. “It was difficult for them to communicate accurately to the communities because they didn’t have adequate training… They had low level of professionalism in how they express themselves.”

And a reliable early detection system cannot rely on chance. Marburg underscored the need for professionalisation and a permanent integration into the national health structure.

Untapped potential

Jonas makes the positive case: if a volunteer health worker cadre could make a difference, a formally trained and equipped frontliner army could change the entire health system landscape in Tanzania – and elsewhere in Africa.

The CHWs selected for the programme need to have a minimum of secondary school education. They undergo six months of intensive training: three months in the classroom, and three months in the field, equipping them to be more than messengers.

Bamvua Ashim Mkundia, a CHW from Luchemi village in Lindi, says that living far from the nearest dispensary, has meant that minor illnesses in her village have often become complicated before treatment is accessed..

“Our presence as CHWs means we can detect [such cases] early and reduce the complications, or even the cost of treatment that they would have incurred,” Mkundia explains. He speaks with striking self-assurance: he has achieved a level of diagnostic knowhow that used to be totally absent from community he lives in.

“Before the training, I lacked an understanding of the tools to use in identifying who is sick and suffering from what,” he says. “But now, I am confident. I can check people’s blood pressure, temperature, and weight, and identify certain infectious and non-infectious diseases.”

For Chiku Abdallah, meantime, being formally trained means a shift in productivity and impact. She serves about 15 households a day. “For each household I visit, I have to provide health education, and that needs no rush,” she notes. Dedicating adequate time to her visits allows her to conduct detailed health education and keep a close watch over community health indicators, like ensuring high rates of child immunization – which is a key responsibility of hers.

Have you read?

Digitally-armed

The CHWs are now equipped with tablets loaded with the Unified Community System (UCS).

Zawadi Dakika, Program Manager for Community Health Programs at the Benjamin Mkapa Foundation (BMF), a key implementing partner, explains how a CHW force with better technological skill is going to solve a historic challenge: fragmented health data.

“Initially, the implementation of community-level health services was fragmented; every stakeholder used their own system,” Dakika says. “Now, all stakeholders use one system.”

She says the tablets are helping the CHWs accurately record data and instantly send reports. “When a CHW is collecting data at a household, if they input high-risk indicators, the system immediately gives them an alert that an urgent referral is required.

“This system helps in fast-tracking referrals, and it will notify the health service centre that a referral is coming from the CHW concerning [a specific condition or threat] so they can prepare to receive the patient.”

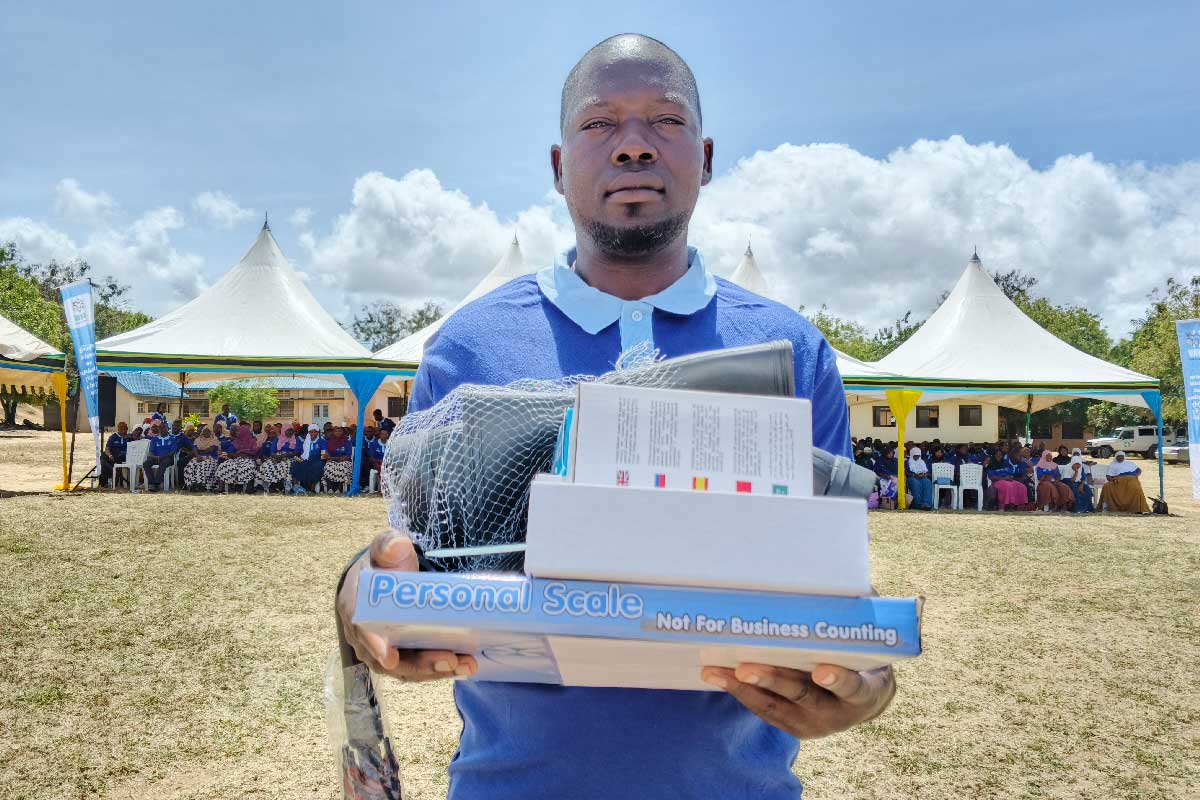

Coupled with the digital system are physical tools, including blood pressure machines, sugar level testers, thermometers and even nutrition assessment tools. CHWs are also provided with practical equipment, like bags to store their gear, and boots and umbrellas for use in muddy, remote areas during the rainy season.

The gear means they can perform their duties effectively, strengthening surveillance for both infectious diseases like Marburg, as well as early detection of non-communicable diseases like hypertension and diabetes, which are often discovered too late.

The strategic importance of this new corps was driven home by the Chief Medical Officer, Dr Grace Magembe, at the graduation of the first cohort.

“They might not wear uniforms or combat gear, but they are an army we depend on heavily,” said Dr Magembe.

By training and deploying this army, the government aims to create a permanent, trusted bridge between the health facilities and the community. This reduces the strain on facilities by stopping health workers from being pulled away from their stations to perform community outreach, Dr Magembe explained.