Why children were missing out on routine vaccines, and how listening helped to close the gap

As India pushes towards universal immunisation, insights from caregivers and health workers in East Champaran, Bihar, reveal why a small but highly vulnerable group of zero-dose children are still being missed.

- 9 January 2026

- 9 min read

- by Ram Ratan

At a glance

Over the last two decades, significant progress has been made to improve immunisation coverage rates and linked outcomes at the global level. In India, the coverage rates have increased from 44% in 2005–2006 to 77% in 2019–2021, according to National Family Health Survey figures. Efforts are underway to push it to more than 90%, but persistent systemic challenges are hindering progress.

East Champaran, a northern district in the state of Bihar, is home to about 350,000 children aged under two. In 2019-2021, full immunisation coverage in the district stood at 68%. A sizeable and acutely vulnerable group among the under-immunised were so-called “zero-dose” children. These are children who have not received their first dose of the basic diphtheria, pertussis and tetanus-containing vaccine. Missing that critical jab means they are more likely to miss out on future vaccinations as well, since administrative records are less likely to contain their details.

We partnered with the William J. Clinton Foundation (WJCF), which already works closely with the Government of Bihar’s State Routine Immunisation Cell, to uncover the deeper and lesser-known reasons for why a small but vulnerable group of children continued to miss out on vaccines – taking a human-centred design approach. This involved listening directly to the caregivers of zero-dose children, associated health workers who navigate these challenges every day and key community members.

Here, we record some of our key take-aways from that analysis.

Understanding the stories behind the numbers

We conducted participatory learning games, in-depth interviews and more informal conversations with community members in three blocks of Bihar over a period of July to September 2024. A few key themes emerged, which offered key insights into the complexities leading to under-immunisation in East Champaran.

Fear and misinformation: a web of doubt

In a quiet village, Radha, a young mother, gently touches the scar on her baby's upper arm. “It hasn’t faded,” she whispers. “What if it’s still poisoning her from the inside?” Instead of seeing the scar – a physical record of the Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine against tuberculosis – as a mark of protection, Radha and others interpret it as evidence of harm.

One mother says, “The mark means it hurt my baby.” These fears are an understandable consequence of a lack of information. In another home, a grandmother asks, “We never took vaccines. Nothing ever happened to us. Why does this child need them now?” No one had ever explained the benefits of immunisation, leaving caregivers confused and afraid.

Without structured communication tools or community engagement, mild side-effects often snowball in the retelling into village-wide cautionary tales.

Local health workers have felt the weight of that mistrust. One auxiliary nurse midwife (ANM) shares, “They say I gave the wrong injection. But I opened the vial in front of everyone.” However, facts don’t always override fear. “The swelling wasn’t normal,” one father claimed, after his child developed a fever post-vaccination. “Maybe the injection was wrong, that’s why it festered.”

Without structured communication tools or community engagement, mild side-effects often snowball in the retelling into village-wide cautionary tales. One mother’s traumatic experience still lingers in her village: “After three injections during delivery, my baby developed a fever. His eyes rolled back; we were terrified. Since then, no one here agrees to vaccinate.” Her words echo, a stark reminder of how fear, once rooted, can shape health decisions for years to come.

Gender and social influence: when tradition overrides health

In many households, women are not empowered to take healthcare decisions for their children. In one such home, Sunita quietly tells an Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) worker, “My husband doesn’t allow me to take our baby for injections.” Even though her husband works far away, his word is final.

In East Champaran, countless mothers face similar constraints, often needing approval from their in-laws or husbands before seeking care. “If my in-laws object, how can I take the baby?” Sunita asks, her voice heavy with resignation. Stories like hers are all too common. Many mothers also sometimes report being scolded by their in-laws for insisting on getting their babies vaccinated. ASHA workers – trained community health workers who help families to access essential health services – often hear such whispered confessions: “I am not allowed to step out. What can I do?”

Deep-seated traditions and social norms continue to shape health behaviours in complex ways. In some homes, myths have taken hold. One mother shared, “For a month [after the birth delivery], we don’t go out, we don’t work. Someone might curse the baby.” The belief that infants must be kept hidden from the ‘evil eye’ reflects how cultural narratives can shape and sometimes restrict health-seeking behaviour. These complex belief systems require thoughtful, culturally sensitive engagement strategies that respect local contexts while gently encouraging positive health practices.

The invisible load of ASHA workers

ASHA workers are the critical link between healthcare systems and communities, but they’re stretched thin. In Bihar, each ASHA is responsible for an average of 1,241 individuals, significantly higher than the national average of 979. As one ASHA candidly shared, “If I explain everything to every household, I won’t finish my mandatory rounds.” Many do the minimum: knocking, giving a quick reminder, and then moving on to the next house. Caregivers, too, notice the gaps. “She just tells us from the door to come for vaccination. She should come inside at least,” one mother says.

So, what’s missing? Tools and health worker training

Many ASHAs haven’t had their mandatory refresher training in years. “I only remember what’s worked over time. The technical details are gone,” one says. Without structured tools, their ability to explain the benefits of vaccination is limited.

Community-led innovations: ground-level solutions with promise

To address the barriers uncovered in East Champaran, the next step was to collaborate with parents, community members, health workers and health system officials to develop practical, culturally grounded solutions to the problem of non-vaccination.

Three tools, the ASHA Routine Immunisation (RI) Flipbook, Shishu Suraksha Card (Child Protection Card) and the Routine Immunisation Rewritable Wall Painting (publicly visible information about the next vaccination camp in the local community) were designed as practical, visual, and community-driven solutions. These interventions prioritise ease of use, accessibility and sustainability, ensuring they align with the community’s needs.

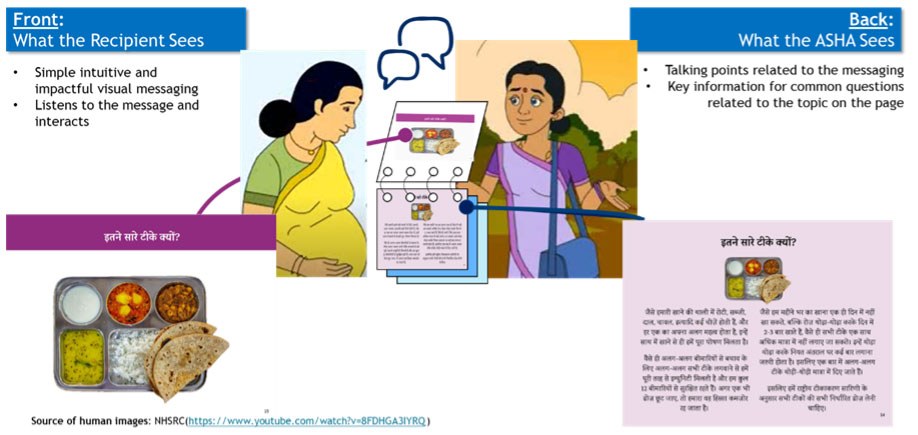

ASHA Routine Immunisation Flipbook

ASHA workers often lacked the tools to explain vaccines clearly and consistently. Overburdened by their workloads, many could only offer hurried reminders, leaving caregivers with lingering doubts.

Recognising that each family responds to different motivations, the flipbook was designed as a flexible communication tool, a bouquet of tailored messages to support vaccine uptake. Developed collaboratively with the key stakeholders such as parents of unimmunised children, the flipbook features simple, relatable visuals to explain how vaccines work, why they’re important, and potential side-effects. With key talking points on the back of each page, ASHAs can deliver consistent, accurate information without relying solely on memory during home visits (see Figure 2).

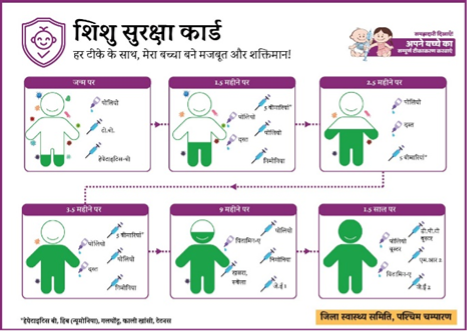

Shishu Suraksha Card

Many caregivers struggled to remember vaccine schedules and how to manage common post-vaccination symptoms. Families can feel unsupported after vaccination, especially if they are dealing with side-effects such as the common, harmless and temporary fever and swelling that often follow. The Shishu Suraksha Card (SSC) was designed as a practical, visual solution to bridge these gaps. Resembling a child’s growth chart, the card depicts each vaccine as a protective ‘shield’ added in a cartoon child’s body, reinforcing the message of cumulative immunity. On the reverse, the card includes easy-to-understand guidance on managing common side-effects, upcoming dose dates, and space for the ASHA’s contact number.

Routine Immunisation Rewritable Wall Painting

In communities where immunisation reminders were typically shared only with mothers during home visits, many decision-makers, especially men and elders, remained unaware. The Routine Immunisation Rewritable Wall Poster brought this information into public spaces. Updated weekly by ASHAs, the poster lists upcoming session dates in visible community spots like shops and Anganwadi centres, turning vaccination information into a collective reminder.

Through the ongoing implementation phase, we are learning that these interventions have been effective in directly improving the vaccine and other programmatic knowledge of ASHAs, which in turn is helping to keep up the knowledge level of caregivers. Consequently, caregivers who earlier were less aware about vaccines their child is eligible for, are now able to recount such important details. With the support of information available now through the intervention prototypes, caregivers feel more confident in their abilities to face and manage adverse events following immunisation (AEFI).

Based on the common learnings and reflections from our experiences, we are outlining implementation-based recommendations that may benefit researchers and policymakers:

Communities know what they need; we just have to ask: The most relevant inputs for the solutions we designed came from the caregivers and frontline health workers. Each intervention concept that emerged out of the community inputs addressed multiple barriers to immunisation. Barriers often were multi-dimensional in nature, but were represented well in the design consideration, since people navigating those barriers on a daily basis were involved in the design process. Furthermore, when communities design solutions, those solutions naturally respect local traditions while promoting healthier practices.

Visual storytelling builds confidence where literacy levels and trust are low: In areas with limited literacy, pictorial and visually rich explanations proved more effective than oral or written communication, as they made complex concepts intuitive. The illustrations used in the flipbook helped caregivers better understand how vaccines work, why side-effects occur, and when/how to seek care, improving comprehension while reducing fear and misinformation.

Equipping ASHAs strengthens last-mile delivery: At first, many ASHAs were hesitant to use the flipbook due to low confidence and uncertainty about how to communicate technical details. Targeted refresher trainings and cluster meetings helped close these knowledge gaps, providing clarity and reassurance. With continued practice, ASHAs began using the flipbook more confidently during their routine household-facing visits. The visual aids offered a clear structure for discussions, reduced reliance on memory, and enabled them to explain vaccine benefits and side-effects with greater ease – ultimately improving caregiver engagement and trust. Investing in health worker-centric intervention can prove more efficient and operationally effective.

The power of co-design and adaptation

These interventions demonstrate that improving immunisation requires more than just service delivery – it relies on trust, communication and community ownership. When caregivers and health workers co-create solutions that fit their everyday workflow, even simple tools can have lasting impact.

ASHAs shaped the design’s practicality, caregivers helped simplify visuals, and local health officials ensured alignment with government standards. Our experience with taking a community-centric approach to design solutions, especially for a deeply entrenched problem such as zero-dose children, indicates a promising outlook to pushing immunisation coverage rates to 90% and beyond in India.