“We don’t want to end back at square one”: Keeping child immunisation alive in Kenya

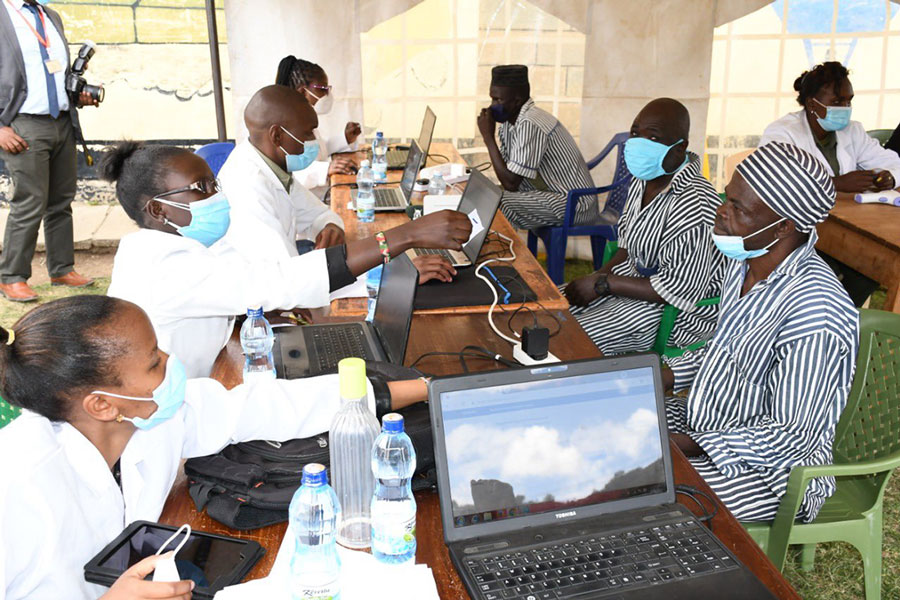

Kenya’s community workers fight to continue vaccinating children during the pandemic to avoid the reversal of historic gains.

- 25 August 2021

- 5 min read

- by Mukami Mungai

Joshua Omanga is one of about 86,000 community health workers in Kenya working to reduce barriers to healthcare for communities who are unable to access health services easily.

He works in the inner-city urban slums of Kenya’s capital, Nairobi, paying daily visits to his patients, mainly children, in their homes. Omanga moves from house to house providing a suite of healthcare services: immunisation, checking acute malnutrition cases, deworming, providing Vitamin A supplements, treating malaria and diarrhoea, and providing advice on family planning.

“My area of coverage has 15,000 children and I had a daily target of vaccinating 400 children. I’m proud to say that I reached my target, though it hasn’t been easy”

When the Kenyan government announced the first case of COVID-19 in March 2020, Omanga's life was thrown into a spin. Faced with a lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) meant that he couldn't visit his patients as often. The community was also apprehensive of health workers like him as they viewed them as potential COVID-19 carriers.

“There are many children who require my services, which needs physical contact with them. I was doing an average of 20 home visits daily but, because of the COVID-19 pandemic, I had to reduce the number of patients to 12. Children were at risk of vaccine-preventable diseases,” he says.

Credit: Joshua Omanga

To mitigate the risks of COVID-19 transmission, and ensure that child immunisation continues, despite the challenges, health facilities are now providing community health workers like Joshua with the proper gear to protect his patients and himself from infection.

When Joshua reports to his workstation in the morning, he starts by conducting a COVID-19 self-assessment including checking his body temperature and other symptoms that are associated with COVID-19. He then packs his immunisation kit and puts on a surgical mask before heading out to the community. He ensures that he carries enough disposable gloves and hand sanitiser to use when visiting patients across the urban settlements. Joshua adds that the availability of protective equipment means that his work doesn’t pause.

He just finished participating as a vaccinator in the second phase of a major polio vaccination campaign in Kenya.

“My area of coverage has 15,000 children and I had a daily target of vaccinating 400 children. I’m proud to say that I reached my target, though it hasn’t been easy,” he says.

“Before the COVID-19 pandemic, I could vaccinate up to 600 children daily, on campaigns such as this, however, it’s now harder to do,” he adds.

He attributes this to other challenges including that concerned parents may not fully understand which vaccines are being administered to their children which can fuel misconceptions about COVID-19 vaccines.

Have you read?

“Some parents have been cooperative whilst others are hesitant because they are worried about the multiple vaccinations their children are getting, often at the same time. Some say I’m overdosing their children. I try my best to debunk the myths by assuring them that combinations we give carry no health risks,” says Omanga.

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Executive Director Dr Henrietta Fore has noted that “As the pandemic progresses, critical life-saving services, including immunisation, will likely be disrupted, especially in Africa where they are sorely needed. At the greatest risk are children from the poorest families in Africa. At a time like this, these countries can ill-afford to face additional outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases.”

Maria Anastacia is a community health worker in Soweto, an informal settlement in Nairobi. When the pandemic hit, Anastacia was worried about her safety. As a critical worker, her job entails closely interacting with the members of the communities she serves.

“I could not conduct community outreach without adequate protection gear. We were told to either stay home or else do our job unprotected. How could we put ourselves, our families, and our communities at risk? This meant that many of my clients had to wait without getting the health services they needed,” she says.

The interruption happened from April to June 2020 after which the Health Ministry began supplying community health workers with adequate personal protective equipment, ensuring the safety of both the frontline health workers and the community.

Anastacia is part of the Kenyan Ministry of Health’s campaign against measles, rubella and polio. Apart from administering vaccines to children, she also ensures that the rest of the team stick to the guidelines on safe implementation of house-to-house vaccinations. She marks the fingers of vaccinated children and marks doors on households whose children have been vaccinated.

“I ensure that the team avoid direct contact with the people they encounter and that they perform hand hygiene when there has to be contact with a child or a caregiver," says Maria.

Omanga and Anastacia are calling on the Kenya government to focus on children who have missed vaccine doses during the pandemic and to ensure that child immunisation programmes remain robust and reach those that need vaccines the most. They also want the government to continue building the capacity of community health workers to avoid reversing the hard-fought public health gains they have achieved.

Doctor Christine Karanja, a paediatric infectious diseases specialist, warns: “If you interrupt an immunisation programme, you create a cohort of unvaccinated children and put them at risk of infectious diseases that have almost been eradicated. We don’t want to end up back at square one.”