A year after a historic epidemic, cholera is in retreat in Zambia

Whether by exposure to the bacterium or vaccination, many more Zambians have immunity this rainy season. But health workers and experts warn that hygiene and sanitation improvements are needed for long-term safety.

- 13 May 2025

- 6 min read

- by Fiske Nyirongo

In January 2024, Gift Mwale received unsettling news: her live-in housekeeper had been admitted to Kalingalinga Health Centre, a Level 8 district health facility in Lusaka, Zambia, with cholera.

Working in the health sector herself, Mwale understood the gravity of the situation. Not only the housekeeper, but also the remainder of the household were at risk. “I was calm, but there was a little voice at the back of my head telling me to worry,” she recalls. “I was very close with my helper at the time, and I knew that the infection rates were serious from my workplace and the news.”

Since October 2023, thousands had been affected by a fast-moving cholera outbreak: by February 2024, the Ministry of Health would report more than 17,000 cases across the country.

Fighting back

In January 2024, Zambia applied to the global oral cholera vaccine (OCV) stockpile, a Gavi-supported emergency repository managed by the International Coordinating Group on Vaccine Provision (ICG), for a shipment of vaccine doses. Within three days, the Ministry of Health heard back: they’d been approved for 2.2 million vaccines.

“Our response has focused on case management, clean water provision, sanitation and hygiene promotion. We are further enhancing prevention efforts with cholera vaccines. We are happy to announce the arrival of the first batches of oral cholera vaccines in the country,” then-Minister of Health Sylvia Masebo said in a press statement that month.

The OCV campaign, concentrated in high-risk areas, aimed to curb infections by vaccinating frontline workers and residents in severely affected locations.

In December 2024, an outbreak in Nakonde, a border town between Zambia and Tanzania, demanded an adjustment of the plan, and the Ministry of Health announced additional vaccine allocations.

“Since Nakonde was not one of those hotspot communities we had earlier planned for oral cholera vaccination, we have, in a joint collaborative manner, engaged WHO, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, and other key stakeholders in mobilising an additional 197,000 vaccines for Nakonde as we re-direct what is available in-country to Nakonde,” clarified Acting Minister for Health Douglas Sykalima in a statement.

The rapid intervention helped reinforce Nakonde’s cholera response, preventing further spread in the border region, and protecting residents from large-scale infections.

Shifting cholera patterns

The 2023–24 cholera crisis was Zambia’s worst since 1992. However, despite the fact that the 2024–2025 rainy season has been a particularly heavy one, there’s been a marked decline in cholera incidence compared not only to the previous year, but to the average annual incidence for the past decade.

Why? In a nutshell, the previous year’s epidemic is likely to have boosted population immunity by exposing more people to Vibrio cholerae, the causative bacterium. But a comparative study run by the Centre for Infectious Disease Research in Zambia (CIDRZ) suggests that the role of the responsive vaccination roll-out is not to be disregarded. Researchers found that immune gains at an individual level not only equalled but even outstripped the immune response elicited by a survived brush with the disease.

“This study enrolled 50 participants during a cholera outbreak in Eastern Province and 56 vaccinated individuals in Central Province,” the report states. “We observed significantly higher antibody levels in those fully vaccinated (two doses of OCV) compared to those who acquired immunity through infection.”

With cholera, neither vaccine-induced immunity nor immunity from natural exposure last forever, explained Harriet Ng’ombe, cholera researcher and lead author of the study – but just a year on, vaccinated and exposed people likely remain under a slowly-waning immune shield.

“Protection wanes after about three years, but antibody levels drop even sooner – sometimes within six months. The key is that even when antibodies decline, the body remembers the pathogen and can still fight against infection.” A 2021 study Ng’ombe led in the Lukanga Swamps furnished evidence that immunological protection could persist for “a few years”.

Reactive, or pre-emptive?

From a public health standpoint, there’s a significant difference between a reactive vaccination campaign and a preventive one. Since 2016, Zambia has deployed both strategies. But since the vaccine in use is the same, there is no reason to think a vaccine dose deployed reactively won’t also play a preventive role – warding off the risk of cholera resurgence in the subsequent months, even years.

Despite this, Ng’ombe emphasises that attributing Zambia’s lower cholera rates in the 2024/25 rain season solely to vaccination in the previous year would oversimplify the situation. Research indicates that many cholera infections are asymptomatic, meaning far more people may have been exposed to the bacterium than case numbers reflect. That widespread exposure, alongside vaccine-induced immunity, likely combined to contribute to the decline in reported cases.

What’s changed in Kalingalinga and Bauleni?

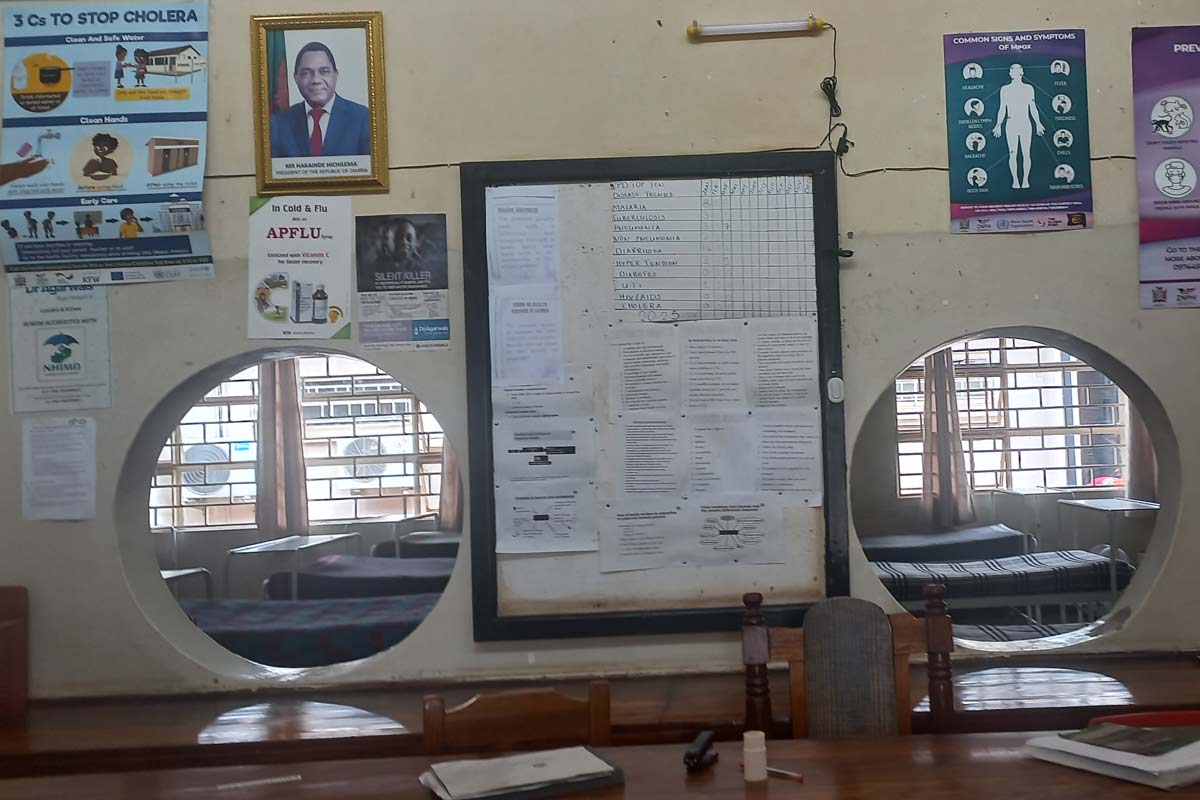

Regardless of its source, the effect of higher levels of immunity in the population on the ground is relief. In Kalingalinga Township, a densely populated settlement in Lusaka, the district health centre sits at a busy intersection, but its in-patient wards are quiet. It’s a stark contrast from a year earlier.

Sister-in-charge Chisuwe Kapumba-Kafulubiti, reflecting on the improvement, points to two once-overcrowded wards:

“During the last outbreak, these wards were full. But as you can see, we have no patients this time around. Thankfully, we haven’t had admissions like last rainy season.”

She credits the reduction in cases to the combined effects of vaccination and community health efforts, saying, “We can now allocate resources to other health priorities beyond cholera outbreaks.”

In Bauleni Township, another high-risk area, Community Health Volunteer Beauty Simpute played a vital role in educating residents and ensuring widespread vaccine uptake.

She describes herself as a bridge between health professionals and communities: “Like with other campaigns, I was trained on the oral cholera vaccine, its importance, how to check for damage in the bottles containing the vaccine, and how to administer it safely,” Simpute explains.

Her team carried out door-to-door vaccinations, established outreach points at churches and markets, and conducted follow-up mop-ups for households that initially missed the vaccine.

“We saw overwhelmingly positive responses from the community,” she says. “People were eager to receive the vaccine, especially after seeing fewer new cases.”

Have you read?

A personal transformation

For Mwale, the outbreak reshaped how she viewed hygiene and disease prevention.

She took the oral cholera vaccine a few days after her helper’s diagnosis and ensured her entire household got vaccinated. Though reluctant to share any identifying information about her former housekeeper, Mwale confirmed that she also took the vaccine – a functional immune-booster following natural exposure – after getting better.

“I always thought cholera was a disease far from me,” she admits. “But I’ve realised how easily it spreads if we relax our hygiene. My helper recovered and went back to school to pursue a health career, and I now remind everyone in my house to wash their hands and clean fruits before eating. Hygiene is the foundation, and all other efforts build on that.”

She sees vaccination, education, and hygiene as interconnected forces in fighting cholera, an outlook echoed by health workers across Zambia – and a reminder that the window of security provided by impermanent immunity is best used to shore up the sanitation systems that can snuff out cholera risk for good.