Chikungunya, spreading fast this year, visits Mombasa for a third time

Climate change is spurring a spike in the mosquito-borne virus, which can cause chronic and debilitating joint and muscle pain.

- 16 October 2025

- 5 min read

- by Diana Wanyonyi

Mariam Chembe’s house in Ziwa La Ng’ombe village in Mombasa, Kenya, is filled with the aroma of coconut oil and jasmine, as she massages the scented balm into the legs and hands of her five-year-old son.

The child, along with two more of Chembe’s children, recently suffered a bout of chikungunya, a mosquito-borne viral disease that is spreading ever further as the global climate changes. Between January and the end of September this year, more than 445,200 suspected and confirmed cases and 155 deaths from the disease were reported globally.

Though mortality rates tend to be relatively low, chikungunya is often debilitating. All three of Chembe’s children suffered headaches, severe joint pains in their legs and fatigue. The youngest’s recovery, in particular, has been slow. For as many as 40% of afflicted people, the disease’s characteristic muscle and joint aches will turn chronic, lasting months or even years.

“We were sitting on a mat under the tree relaxing after taking lunch, and three hours later my toddler started complaining of pains on his legs and persistent headache. Then the other two children started saying they were feeling tired and their head was hurting,” Chembe recalls. “I gave them painkiller tablets, but they didn’t help.”

Her youngest deteriorated quickly. “His eyes started turning red, legs were swelling, he was shivering, and his body temperature was too high,” she says. “His hands started to be stiff; that is the time I took them to a nearby Ziwa La Ng’ombe Dispensary.”

There, the youngest was put on IV fluids for rehydration. “They were all treated and given medicine to take while at home. I felt good seeing all my children treated, and they would walk slowly.”

Tell-tale pain

When her children’s diagnosis was confirmed by lab testing, Chembe was unsurprised. She had seen the disease not long before, in a neighbour’s child. “With all the symptoms that my neighbour’s child had, they were more similar to what my children had, so I ruled out malaria and I knew chikungunya had knocked at my door.”

Its vectors, two species of Aedes mosquito, are common in coastal Kenya, typically biting during the daylight hours. “I suspect that they were bitten by mosquitoes here at home because we have an open crack on our septic tank. I think that was their breeding ground,” Chembe said.

Do we have a chikungunya vaccine?

Two vaccines – Valneva’s IXCHIQ and Vimkunya developed by Bavarian Nordic – have now been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA). IXCHIQ is supported by the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI).

Modelling studies have suggested immunisation against chikungunya could have profound impact. But getting to a mass vaccine roll-out will require more evidence – not to mention World Health Organization approval. Gavi, which supports lower-income countries to purchase vaccines, has put chikungunya vaccines on a Learning Agenda to gather the info necessary for strategic decision-making.

Growing threat

First identified in the 1950s, chikungunya used to be limited in its range, but by the end of 2024, 199 countries spanning every continent but Antarctica had seen cases of the illness.

In Mombasa, this latest outbreak was the third on record, following outbreaks in 2018 and 2021. “We noticed increasing numbers of patients in our public hospitals who most of them complained about high body fever, lack of appetite and painful body joints, and after doing medical investigations the results showed that it was indeed chikungunya,” said Hildergard Wasike, Mombasa County Public Health Officer. The county health department warns that children under the age of five are most affected.

To curb chikungunya and other mosquito-borne diseases like malaria and dengue fever, Mombasa County has rolled out vector control measures, and intensified evening fogging operations – using a van to mist an aerosolised insecticide – across the city.

To support these efforts, members of the public have been urged to clear clogged gutters and cover water tanks that are open, eliminate stagnant water from containers, cans, tires and coconut shells, to keep their surroundings clean and dry, and also to cut long grass.

Have you read?

Wasike warns that chikungunya symptoms are often confused for dengue or malaria, resulting in mistaken treatment responses. “Many people have a routine of treating themselves by buying over-the-counter medicine to treat themselves at home without going to hospital for check-up.”

Bracing for more

Jane Lusese, a nurse at Sea Side Hospital in Mombasa, says treatment takes the form of supportive care: IV fluids, painkillers and vitamins.

“Ten years ago, this disease was not there,” says Lusese. “The weather pattern has changed… now we encourage parents and guardians to cover children under the treated mosquito nets when sleeping both night- and daytime.”

Mombasa County has deployed 2,400 community health providers to all six sub-counties to help in identifying sick patients in the community. Sixty-five public health officers have also headed out into communities to issue instructions on environmental mosquito control.

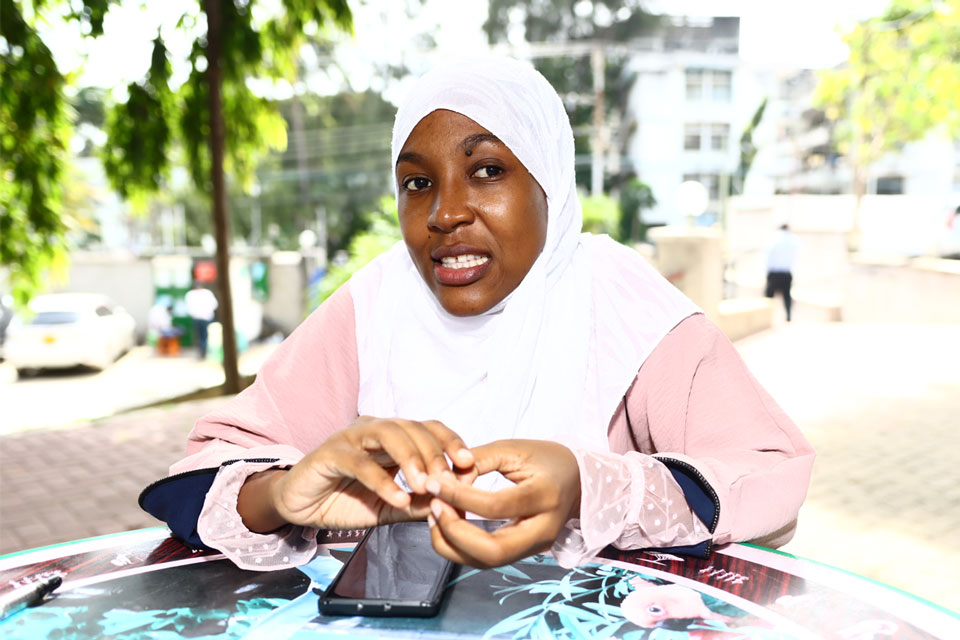

Fatuma Ali, manager at Emergency Operation Center (EOC) within in Mombasa County’s health department, says Mombasa’s tropical climate is conducive to the mosquitoes that spread chikungunya and dengue. She also says the county is planning to run a vector surveillance project to monitor population levels.

The EOC acts as an early warning system for outbreaks. “These systems helps us to communicate to our community quite early enough for them to be able to apply the interventions, and help them to prevent themselves from further spread,” Ali said.

The system relies on a network of community health promoters, who communicate suspected cases by calling in or texting a centralised call centre. “We also use our databases to look at the trend of disease in the Kenya Health Information System.” If there are unexplained wobbles in any graph-lines, the EOC follows up to “address the issues”.