Gavi-supported countries make strides towards vaccine sovereignty

Countries are “voting with their feet,” says Benjamin Loevinsohn, Gavi’s Director of Immunisation Financing & Sustainability, of an encouraging mid-year co-financing report.

- 2 August 2024

- 9 min read

- by Gavi Staff

At the mid-year point, Gavi-supported countries had paid 60% of the sum due for 2024 in ‘co-financing’ – the proportion of the cost of vaccines borne by governments.

That’s good news for a number of reasons. The most immediate and practical one is that all of that money, a total of US$ 165 million, gets routed to UNICEF Supply Division in Copenhagen for the direct purchase of life-saving vaccines.

Country governments think vaccination is a good buy, and they want to prioritise it. That’s what it says

– Benjamin Loevinsohn, Gavi’s Director of Immunisation Financing & Sustainability

But the readiness of countries to pay their portion on time, and even ahead of time, has a different kind of currency too. It shows, according to Benjamin Loevinsohn, Gavi’s Director of Immunisation Financing & Sustainability, that Gavi-supported countries are invested in vaccination as a “good buy.”

Gavi’s mission is to guarantee equitable access to vaccination – that means countries that need support to protect their populations from vaccine-preventable diseases get help. But, in the interest of both vaccine sovereignty and programme sustainability, the organisation’s support model is designed as a leg-up, rather than a crutch. As economies expand, and become better able to foot the bill, they shoulder more of the cost of immunising their people.

And this year, the timeliness of country contributions is especially encouraging, considering that lower-income countries as a group are spending more on immunisation than ever before: the absolute, aggregate co-financing obligation rose 29% this year against 2023’s level.

That’s because immunisation programmes are expanding, explained Loevinsohn when he spoke to VaccinesWork last week, and because some states among the countries that Gavi supports are doing better economically, and are therefore better able to pay their own way.

Loevinsohn, who comes from Canada and is a physician by training, joined Gavi in late 2021 from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, having spent many years at the World Bank before that. Disclaiming bias – he’s only been at his post for two and a half years, he argues – he calls Gavi’s co-financing model a “beacon.”

“It’s coherent, it makes sense, and there’s a real principle of burden-sharing. And it's been successful. I mean there are some examples where there have been challenges, but 19 countries have successfully transitioned.”

Our conversation, edited for length and clarity, follows.

VW: We’re just halfway through the year, but 60% of the money that country governments are due to contribute towards the cost of vaccines for 2024 has been paid in already. Can you tell us why that’s a big deal?

BL: Well, first of all, it's a big deal because it's faster than we've raised money before. But it's not just that it's 60% – it's the absolute amount of money, too. It's about US$ 165 million that has been paid in co-financing already this year. That's more than was paid in whole years up until 2023 – before 2022, we’d never raised that kind of money.

It’s a real accomplishment, and doing this takes a lot of people. It takes, obviously, the countries themselves, it takes [Vaccine] Alliance partners, it takes people in Gavi’s Country Programmes Delivery department, it takes some people on my team as well. So it's really a team effort to get this done. This kind of success is not achieved by one set of people.

VW: To better understand the significance of that sum – US$ 165 million – what’s the counterfactual here? Put differently: the vaccines need to be purchased. If countries weren’t stumping up this amount of money, where would it be coming from?

BL: Well, if the Gavi model was just providing free vaccine to the 54 countries we support, then we’d have to raise more money from different donors. It would be a lot more money to raise. During [the ongoing strategic period] Gavi 5.0/5.1, we will have raised about US$ 1.3 billion in co-financing. That US$ 1.3 billion would have had to come out of somebody else’s pocket, and I’m not sure it would be so easy to find those pockets.

Beyond just the money, though, I think there is something about the commitment and the interest of governments to bear some of the costs of vaccines themselves. They’re obviously voting with their feet! If countries didn’t want to pay at all, we’d have much more of a problem – we’d have countries defaulting; and on the contrary it’s going in the opposite direction. We have fewer and fewer defaults, we have more [countries] paying on a more timely basis. That’s pretty impressive.

VW: When you say “voting with their feet” – what’s that vote for? How are you reading that?

BL: I read it as: they know vaccines work. Country governments think vaccination is a good buy, and they want to prioritise it. That’s what it says. And I think they see that vaccination is a necessary part of primary health care.

I think they really do it because they think vaccines and immunisation are a sensible thing to do, and a good buy for them.

- 59.6% of all co-financing payments due in 2024 had been paid by end June

- 67% of countries have made all or some of their co-financing payments for 2024 already

- 80% of co-financing is being paid from domestic budgets

- Countries in accelerated transition have already paid 53% of their co-financing dues, despite a 37% increase in their obligations compared to 2023

VW: One of the reasons that the absolute sum paid in so far this year is so large is because the total co-financing obligation increased by 29% in 2024 against 2023’s baseline. Why did that increase happen? Can you break it down for us?

BL: Right. So about 20%, roughly, of the increase in co-financing is due to new vaccine introductions. As countries introduce new vaccines, like malaria, or like HPV, their co-financing increases. Obviously, that’s a feature, not a bug – it’s great! More vaccines to more children and adolescents.

The second cause of the increase, about 40% or 50%, is due to the roll-out of existing vaccines. So, increases in the coverage of the vaccines, increases in the birth cohorts, so, more children to immunise, and increases in the geographical spread of the vaccines. So, for example, some people started HPV [vaccination] in one area and are now spreading it to more areas. Also, again, a feature not a bug.

Then about 30% of the increase is due the regular functioning of Gavi’s co-financing policies – which basically means that as countries’ economies grow, they pay more of the co-financing. And that’s what we’re seeing: some economies are growing so [countries] are paying more of the cost of the vaccines.

Have you read?

VW: In global health, we talk about the importance of ‘vaccine sovereignty’. Can you tell us a bit about how these latest figures indicate an increasingly robust vaccine sovereignty growing among Gavi-supported countries, and how that relates to sustainability?

I think it’s a good way of looking at what’s happening with co-financing and transition. As countries get richer, they pay more for the vaccines, which also means they’re becoming more independent. That’s really a good thing. The fact that countries transition from Gavi support means that they become sovereign, they procure their own vaccines, etc.

I think that also explains why governments are interested in paying co-financing: they think they should be paying some parts of it; it’s a way of assuring, in the long run, vaccine sovereignty.

On sustainability, we have this graph of how the amount of co-financing has increased over time: it was about US$ 400 million during 3.0 [Gavi’s 2011–2015 strategic period], about US$ 800 million over 4.0 (2016–2020], and it’ll be about US$ 1.3 billion by the end of 5.1 (2025). To me, that’s what sustainability looks like: as countries get wealthier, they pay more. That’s the hard work of real sustainability. A gradual, but steady, increase in what countries are paying – and the fact that countries can transition out of Gavi support is testimony to that.

Now, there are some challenges. Countries that have transitioned out, some of them are backsliding in terms of coverage rates – and we’re trying to address that. No country that has transitioned out of Gavi support has reduced their portfolio of vaccines. Some have added vaccines. There are some vaccines which we still encourage transitioned countries to introduce – but if we can help them do that, that’s great, that’s what sustainability looks like.

VW: Recently, nine African countries signed the Abidjan Declaration. Can you tell us what that is and why that’s important?

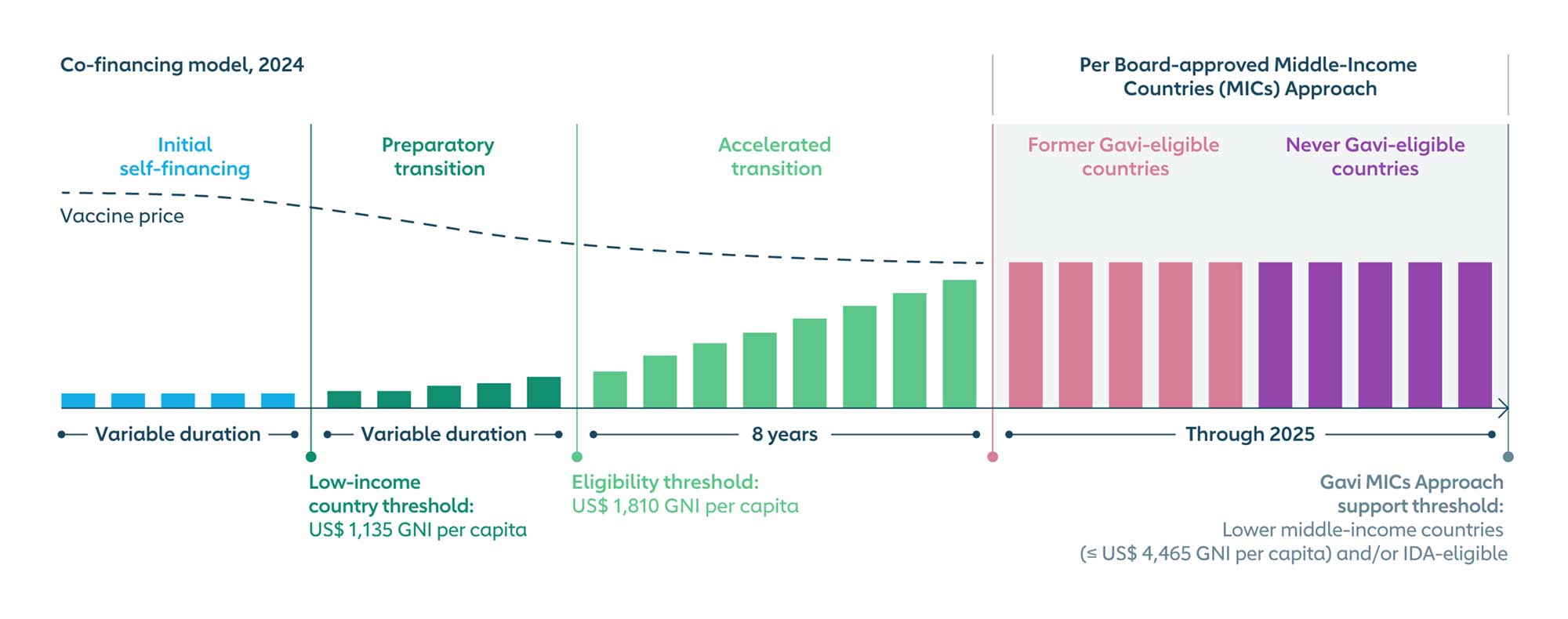

BL: The Abidjan Declaration came out of a meeting convened by the Government of Côte d'Ivoire. They brought together countries in Africa that are in what we call accelerated transition and preparatory transition. So, accelerated transition is where countries surpass a certain GNI threshold, and from that time, they enter a phase in which they have eight years to transition from Gavi vaccine support.

The countries came together and talked about what their requirements were, and committed themselves to becoming independent. They asked for help during this process, and I think both the Gavi Secretariat and Alliance partners as well lined up to support them during this transition period.

What happens when a country can’t pay?

The co-financing contribution is not optional. However, countries in crisis – for example, protracted humanitarian disasters – can apply for a waiver. This year, full or partial waivers are expected to be approved for Afghanistan, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria and Yemen.

VW: These developments are encouraging. Why are they happening now? Or another way of putting this: what’s held back countries in the past?

BL: I don’t think there have been impediments in the past. I think what we’re seeing is the result of increasing expectations.

Our portfolio of vaccines has grown substantially. So really, that’s what we’re seeing. I mean, there are more vaccines that are available that countries can introduce. Their coverage rates are generally increasing over the long term – maybe not always in the short term, but if you look at the long term since Gavi was founded, there’s a 20 percentage point increase in coverage rates.

VW: Did these mid-year figures surprise you when they came in?

BL: Oh, yes! Two months ago, if we had had this conversation, I was a worried guy. We were in a tough situation! There were a large number of countries who hadn’t paid their co-financing yet, due principally to procedural and bureaucratic issues. Releasing budgetary resources by ministries of finance can be very involved, for instance. Sometimes there’s a challenge of mobilising foreign exchange from the country’s central bank to make the payment to UNICEF.

In the past couple of months, however, things have really turned around. I’m a happy man.

More from Gavi Staff

Recommended for you