Five ways that scientists are ensuring the safety of COVID-19 vaccines

As companies race to develop COVID-19 vaccines, some development processes have been run in parallel to stop the pandemic as quickly as possible. Yet safety remains paramount; now that we are on the brink of rolling out some of the vaccines that did well in phase 3 trials, we look into how researchers are ensuring a COVID-19 vaccine is as safe as possible.

- 2 December 2020

- 4 min read

- by Priya Joi

Almost a year after the virus that causes COVID-19 was first detected, one vaccine, Pfizer/BioNTech’s, has been approved for roll-out in the UK, and two others, one by AstraZeneca/Oxford and another by Moderna, have shown high efficacy in phase 3 trials and are seeking regulatory approval. This is an extraordinary achievement given that developing a vaccine can normally take 10-15 years. However, this accelerated development has to come with the guarantee that any vaccine is safe to use in people. Here are five ways that researchers are ensuring COVID-19 vaccines are safe.

1. Safety is investigated at every stage of vaccine development

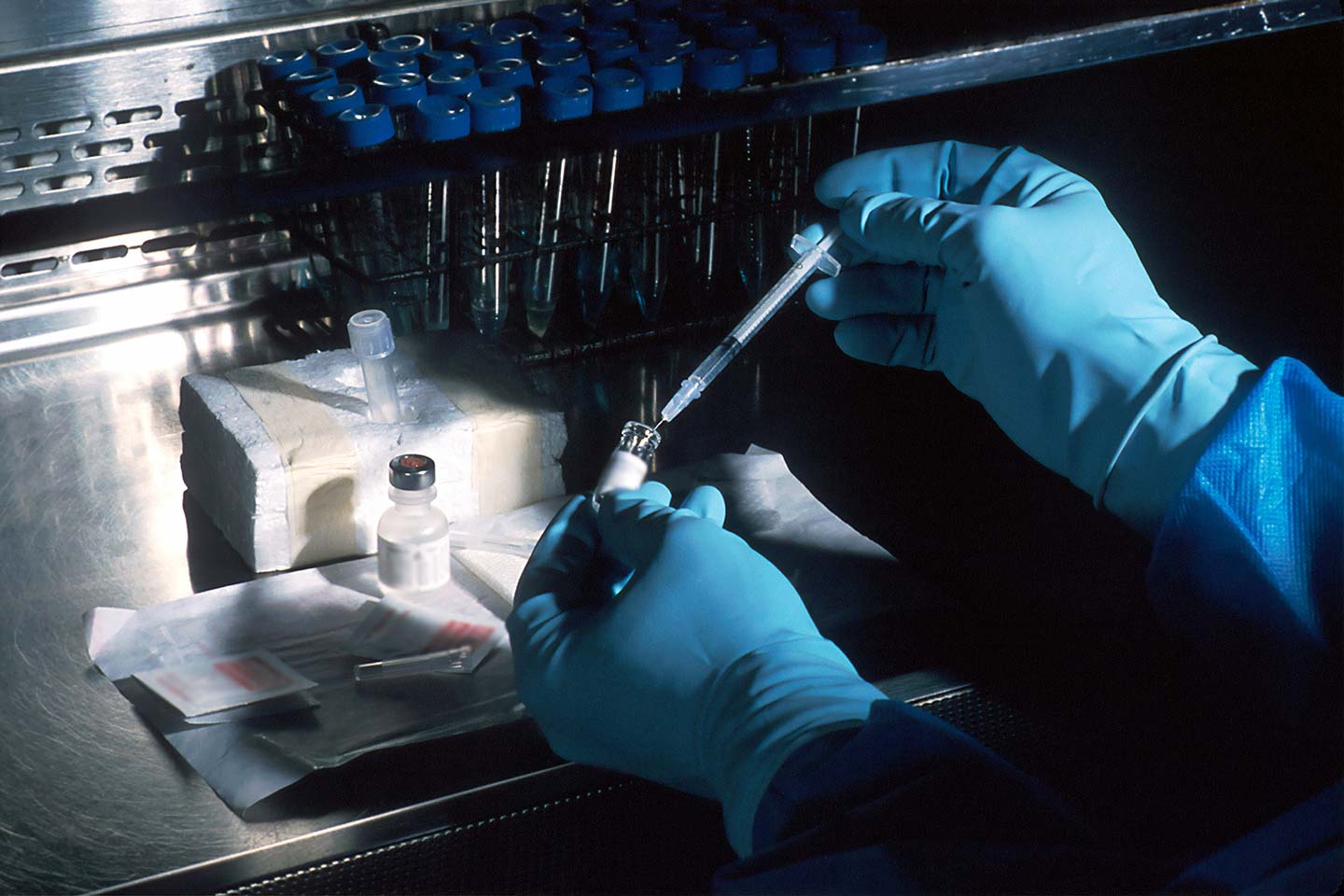

A potential vaccine goes through various stages – right from the exploratory stage, to the pre-clinical stage (often on animals), then clinical development (which includes phases 1-3), and finally regulatory review and approval, manufacturing and quality control.

In animal studies for example, a vaccine is tested for toxicity and to see how it reacts with the body – this is to identify a safe dose before testing the vaccine in people.

Once in human trials, researchers look for ‘adverse events’ or in other words, unwanted side effects in people who take the vaccine. These are not to be confused with mild, temporary effects from taking an effective vaccine. For example, COVID-19 vaccines could lead to short-term effects such as a headache, sore arms, fatigue, chills and fever. This is not uncommon in other vaccines too, but these symptoms are not dangerous in the long term.

Last month, Anthony Fauci, Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said the speed of the phase 3 trials of the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna vaccines “did not compromise at all safety nor did it compromise scientific integrity” but rather indicated extraordinary scientific progress.

Have you read?

2. Monitoring after clinical trials

Serious adverse events that occur shortly after vaccination could be detected in clinical trials, but rare adverse events, and those with delayed onset, are likely to be spotted only once large populations are vaccinated. It is therefore critical that scientists continue to closely monitor people who have been vaccinated, to quickly identify any potential side effects.

3. Global consensus on adverse events relevant to COVID-19 vaccines

One concern with a COVID-19 vaccine is that immunisation could make subsequent infection with SARS-CoV-2 more severe – this so-called “vaccine-mediated enhanced disease” has been seen in animal studies of vaccines against other types of coronaviruses.

It was also seen with the dengue vaccine called Dengvaxia. The Task Force for Global Health’s Brighton Collaboration is a group of more than 750 vaccine experts working on COVID-19 vaccine safety. In partnership with the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) – which, together with Gavi and the World Health Organization (WHO) is driving forward COVID-19 vaccine development – the Brighton Collaboration convened global experts to develop a consensus on how to adequately assess disease enhancement.

In addition, they are drafting lists of potential adverse events of special interest for COVID-19 vaccine candidates which are reviewed by WHO. These events could be respiratory (including pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome), cardiac (including cardiogenic shock, cardiomyopathy or coronary artery disease), acute renal and hepatic injury, or sepsis.

4. Surveillance to determine background rates of adverse events

A critical action by countries waiting for a vaccine is to develop active disease surveillance systems that can calculate the incidence of background rates of adverse events of special interest before vaccine roll out. This will be especially important in low- and middle-income countries that don’t always have large health care administrative databases to undertake such surveillance. One option could be piggybacking on international health collaborations with lower middle-income country (LMIC) institutions that have the potential to be used as active vaccine safety surveillance sites.

5. Developing vaccine safety profiles

Vaccine development companies and country-specific regulatory drug agencies will jointly define how long a vaccine is tested among a certain proportion of the population to generate the data for the safety profiles. The Brighton Collaboration is creating standard disease case definitions for adverse events, which can form the foundation of developing a safe vaccine because they allow for the accurate counting and comparison of adverse events and therefore safety profiles across vaccine trials.