Funny medicine: Hippocrates and the four humours

In Ancient Greece, the physician Hippocrates and his disciples explained the healthy body as composed of four balanced ‘humours’. Their theory of medicine endured for millennia before it was eclipsed – but their teachings still have valuable lessons today.

- 4 August 2022

- 8 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

One autumn somewhere around the year 400 BCE, a man named Philiscus, from the island of Thasus, spiked a fever and went to bed, where he sweated through a comfortless night.

The next day, he was even sicker. On the morning of the third day, his fever seemed to relent, but by night it was back, and more intense than it had been. He was thirsty, delirious, cold with sweat, his tongue dry, his urine black. By day five, his nose bled slightly and his urine was a better colour, but contained floating blobs “resembling semen”. His limbs grew cold, his urine again black, he slept fitfully and little. He breathed like a person “recollecting himself”, at sluggish intervals. His spleen swelled like a tumour, and on the even days of his illness, he suffered fits. In the middle of the sixth day, he died.

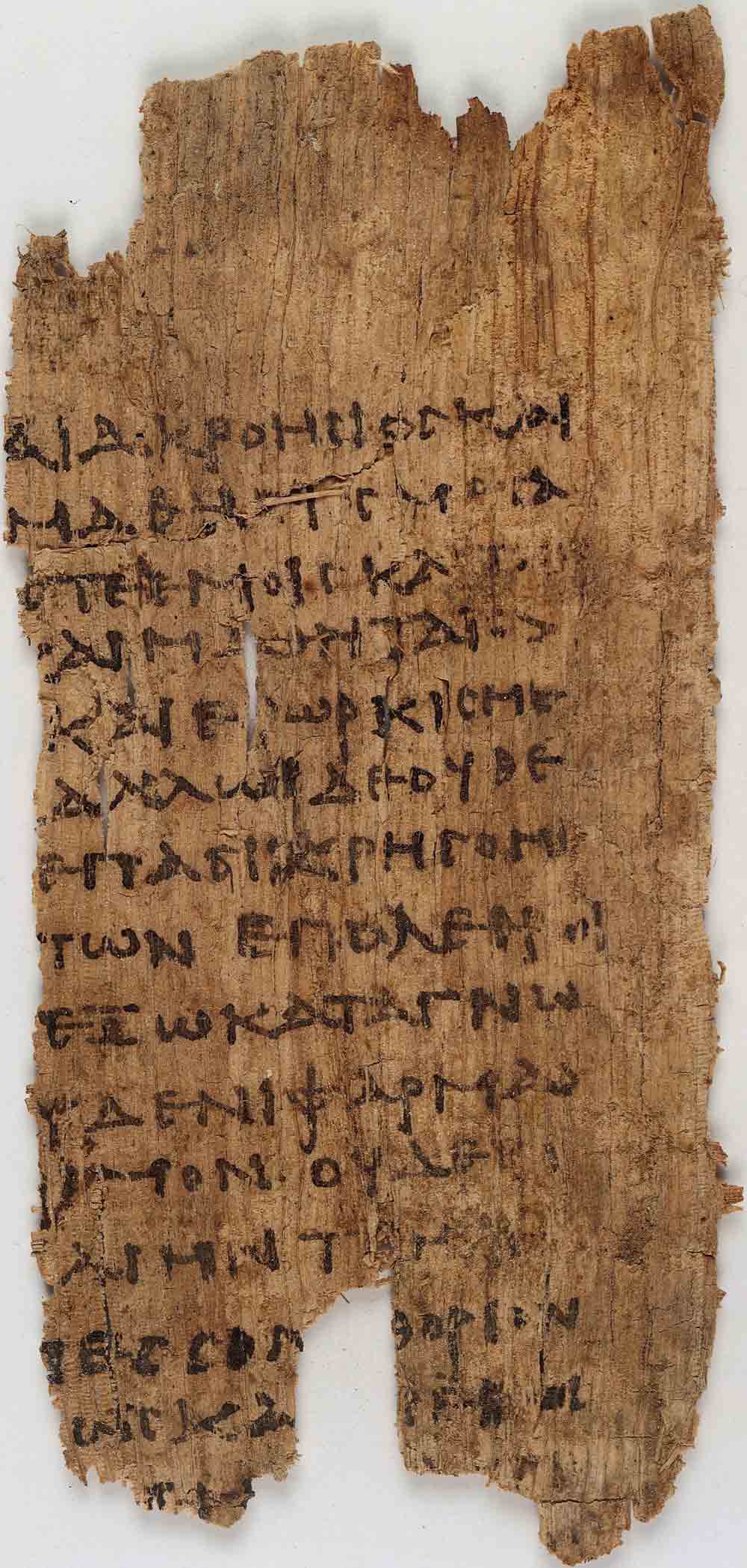

Thousands of years post mortem, the scrupulous, clear-eyed observations of Philiscus’s physicians, recorded in an ancient Greek text called Epidemics 1, one of around 60 medical texts collectively known as the Hippocratic Corpus, allow modern doctors and historians to converge on a diagnosis. Philiscus’s last illness was a case of malaria – specifically the strain caused by the parasite Plasmodium falciparum and delivered into the human bloodstream by the female Anopheles mosquito.

But that diagnosis – and even the concept of a diagnosis – would have been nonsense to the authors of the text, toga-clad scholars who watched over Philiscus, gathered his urine, squinted at the thin trickle of blood from his nose, and applied a remedial suppository to encourage the passing of “some scanty flatulent matters”.

Image source: Wellcome Collection

Rather than considering ill health to consist of different sicknesses with separate causes, the Hippocratic writers – the school of ancient Greek physicians who orbited Hippocrates of Kos, and who authored, with and after their mentor, the texts in the Corpus – understood illness as a process of imbalance, not invasion. The body was a system of four fluid “humours”: black bile, yellow bile, phlegm and blood. If the humours were in balance, then the body was in health. If the humours were in imbalance, then the person was sick. Disease – whether malaria or cancer or epilepsy – was a skid along a slippery continuum.

This explains the Hippocratic physicians’ concern with the emissions and ingestions of Philiscus. The strange-coloured urine and the bloody nose were less symptoms of a disease than disease itself: the body progressing into imbalance. For the Hippocratic doctors, food and drink and various forms of purging — blood-letting, say, or, as in Philiscus’s case, the administration of a suppository — were the main means of restoring the proper relationships of the humours.

In its tidy arrangement of the naturally balanced humours, the body was a microcosm of the universe at large, whose equilibrium depended on four elements – earth, air, fire, and water. These, like the humours, were located at the intersections of two criss-crossing qualitative axes: warm and cool, wet and dry. Echoes were observable in life: the Mediterranean seasons – spring (hot and wet), summer (hot and dry), autumn (cold and moist), and winter (cold and dry) – and the stages of life of man, the temperaments of man (phlegmatic, sanguine, choleric, melancholic).

Of course, the theory was wrong. But it took some 2,000 years for humouralism to lose its explanatory power in the eyes of the Western medicine.

Not that its theoretical dominance went unchallenged. Demonic and religious explanations of disease compelled attention from the first. And new thinkers, faced with new evidence, outlined new aetiological proposals – in the 16th century, for instance, Veronese doctor and poet Girolamo Fracastoro articulated a novel contagion theory.

Fracastoro’s ideas didn’t really catch on, but eventually, cascading, revolutionary scientific discoveries were bound to eclipse humouralism. In the late 1700s, Joseph Priestley and Antoine Lavoisier discovered modern chemical elements and blew up Aristotle’s four-part explanation of what makes up the world. By the late 1800s, germ theory offered a decisive new paradigm for understanding disease.

But if Hippocrates and his students were wrong, they were also brilliant. Here are a few profound and enduring contributions they made to medical thinking:

1. Understanding illness as a natural, rational, observable thing

Until Hippocrates, illness was a capricious and supernatural thing – a whim of the gods, a punishment, a possession by demons. Hippocratic aetiology was a radical leap: “What is important here is that these medical writers are asking not, ‘Who causes this sickness?’ but rather, ‘“By what process does this sickness occur?’” writes historian Ann Ellis Hanson.

In other words, the Hippocratics’ foundational assumption that disease was a natural, observable, predictable thing propelled by natural causes was nothing short of “the cognitive foundation on which scientific medicine was built,” writes Yale historian Frank M. Snowden in Epidemics and Society: From the Black Death to the Present. Snowden quotes Charles-Edward Winslow, an epidemiologist writing in the 1940s, who explained, “if disease is postulated as caused by gods, or demons, then scientific progress is impossible. If it is attributed to a hypothetical humor, the theory can be tested and improved.”

2. The medical case history

Philiscus’s case report numbers among many in Epidemics, each attentive to the symptoms and personal qualities of the patient, and heedful of the conditions in which they were living when they became sick.

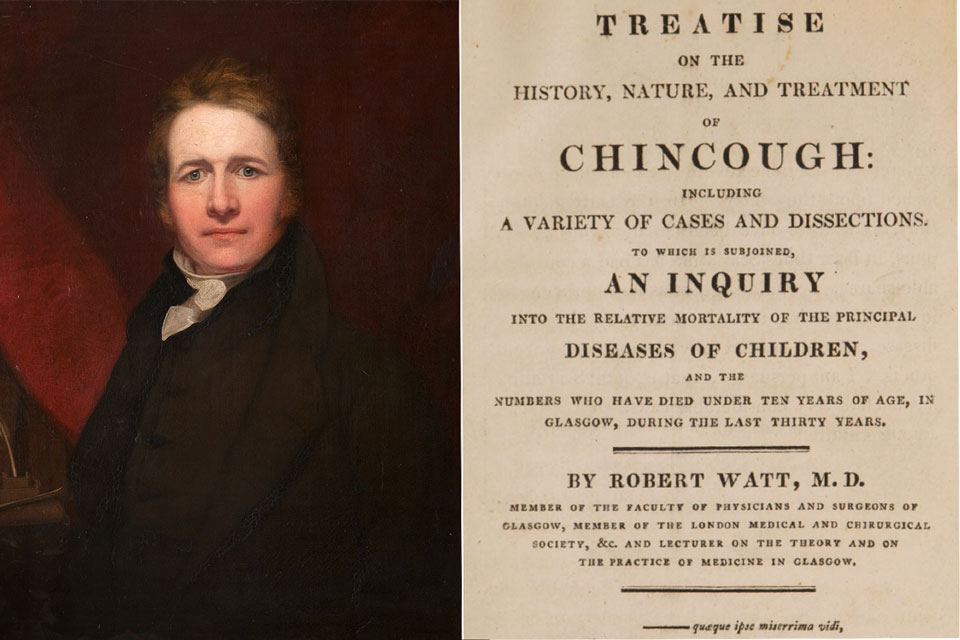

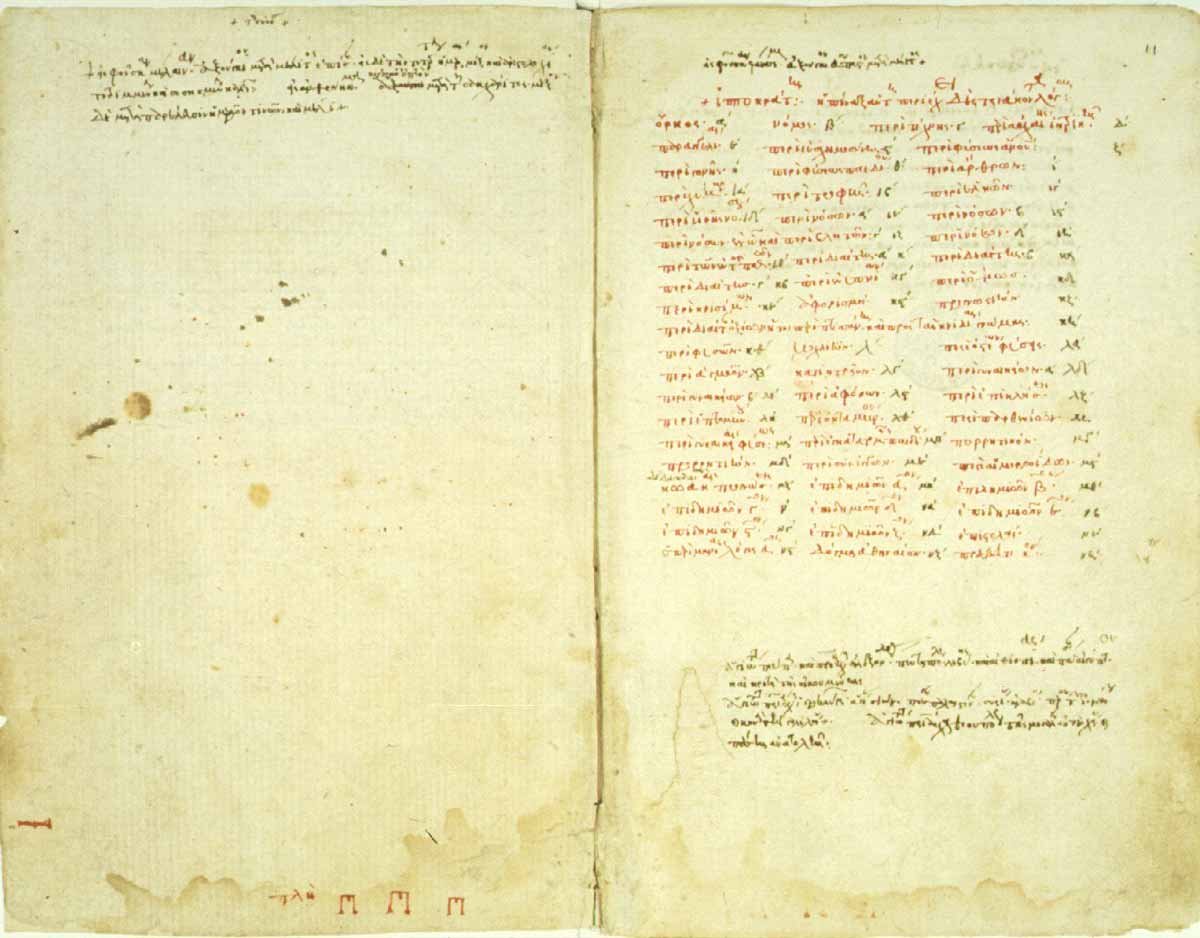

Image source: Online Vatican Exhibition

While these are not the first case histories on record – the first known such reports date from c. 1600 BCE in Egypt – the Hippocratics established this kind of objective, detailed observation as a medical standard. Galen, a doctor living in the second century AD, arguably Hippocrates’s greatest posthumous student and populariser, took the tradition forward, adopting a more personal, conversational tone in his reports.

The Hippocratic case histories allowed for the consideration of patterns, for the articulation of implicitly testable assumptions. For instance, in Epidemics, the authors consider that in cases of “ardent fevers” like Philiscus’s, a “proper and copious haemorrhage from the nose” generally saved the patient. Philiscus and two other patients who experience just a “trifling epistaxis” die.

3. Prognosis

There’s an easily traced line from the gathering of case notes, to the observation of patterns, to prognosis.

“It appears to me a most excellent thing for the physician to cultivate Prognosis,” wrote Hippocrates, or one of his circle in the Prognosticon, “for by foreseeing and foretelling, in the presence of the sick, the present, the past, and the future, and explaining the omissions which patients have been guilty of, he will be more readily believed to be acquainted with the circumstances of the sick; so that men will have confidence to intrust themselves to such a physician.”

Have you read?

Vital here is the consideration of past, present and future together – a progressive, connected story of health. For the Hippocratic doctor, this understanding was the central concern. As nature was the cause of disease, so it was the primary healer – the doctor’s job was to assist nature, rather than defeat it. Intervention needed to be weighed carefully. “Life is short, the Art long; opportunity fleeting, experiment treacherous, judgment difficult,” Hippocrates famously cautions.

4. A defined medical ethics

The Hippocratic oath, which remains a synecdoche for medical ethics in modern times, codified that circumspection into a pioneering series of guidelines, sworn to in the name of “Apollo the physician, and Asclepius, and Hygeia and Panacea, and all the gods and goddesses.”

Image source: Wellcome Images

Among other pledges, the physician swearing the oath commits to prescribe the dietary regimes which will “benefit my patients according to my greatest ability and judgement, and I will do no harm or injustice to them,”; foreswears the knife; promises not to seduce men or women in the homes of the sick; promises never to administer a lethal drug; and guarantees to keep secret what is heard or seen of the lives of patients. In short, it is a ranging and farsighted document of the weighty moral responsibility that the Hippocratics understood themselves to shoulder.

NB.: It is not a universal standard for doctors today to swear any oath, and those that do, commit to a modified covenant – not, for instance, swearing by Apollo, or promising never to touch a scalpel.

5. A parting lesson: beware the cult of authority

Hippocrates was above all an observer, but, according to Frank Snowden, his empirical approach became a “frozen doctrine” as they passed through the hands of Galen. “To Galen, Hippocrates was the permanent fount of medical science, and the main tenets of his doctrine were unalterable,” writes Snowden. His ideas could only be perfected.

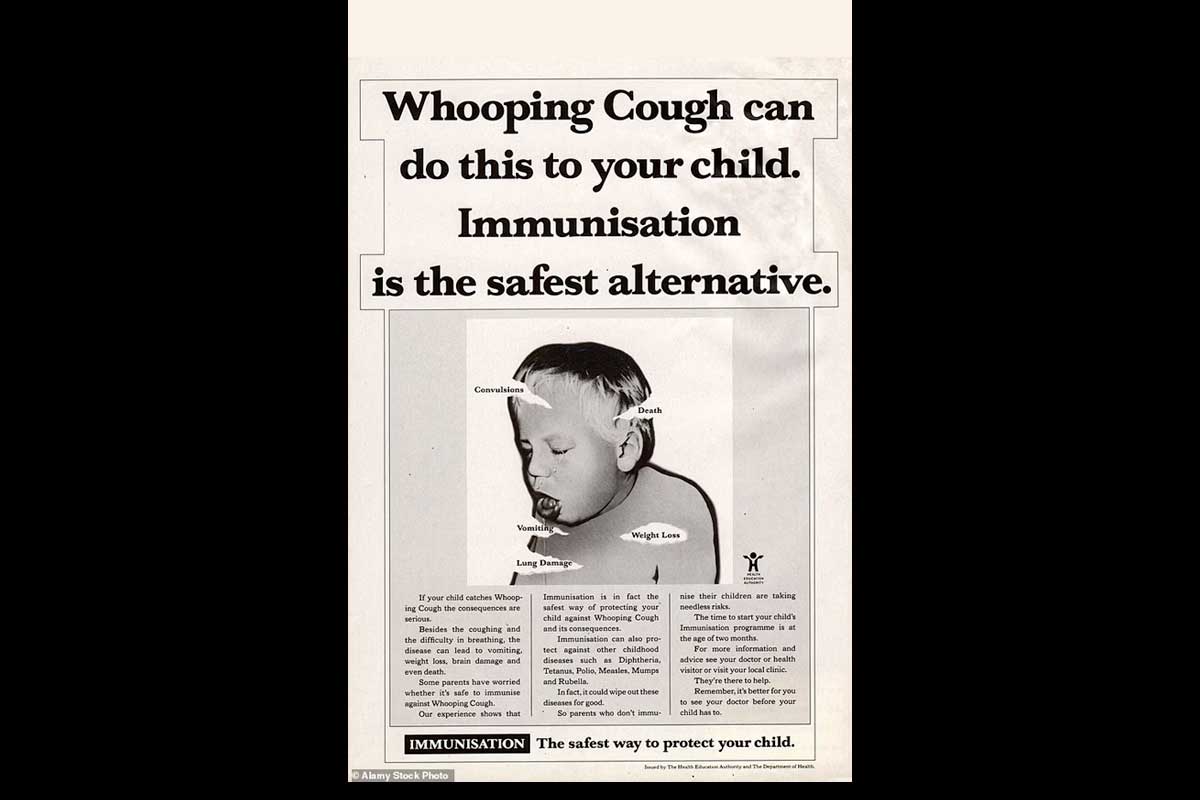

Image source: Wellcome Collection

In fact, though Hippocrates’ personal biography was scanty, an idealised myth of the man developed in this era. Hippocrates was descended on his father’s side from the Greek god of medicine, Asclepius; on his mother’s side from Hercules, people said. In the process of his apotheosis, “the original foundation of the Hippocratic corpus – direct observation at the bedside – was replaced by the mastery of the texts of both Hippocrates himself and his authoritative interpreter, Galen,” Snowden says.

Does this ossification of knowledge explain why the four humours persisted beyond the point that they could reasonably have been claimed to explain the movement of disease? Hard to say. But surely an open, evidence-based science – arguably, a more Hippocratic approach – would have retired humoural pathology well before the 19th century.

Further reading:

For a discussion of the evolution of the four humours theory, see Jacques Jouanna's “The Legacy of the Hippocratic Treatise The Nature of Man: The Theory of the Four Humours” from Greek Medicine from Hippocrates to Galen.