In Ghana, a game of post-pandemic immunisation catch-up is being hobbled by vaccine shortages

Closing the COVID-19 immunity gap to make sure Ghana’s children are protected is only possible when there are enough vaccines in clinic refrigerators.

- 9 March 2023

- 6 min read

- by Nanama Boatemaa Acheampong

“When COVID-19 came, we had a huge human resource shortage,” says Gloria Danquah*, a disease control officer for Okaikwei North in Accra. “We had to conduct some outreach programmes with our community health nurses because our static clinics were not active, but the same people who were supposed to go into the communities to provide vaccination services were the ones in charge of contact tracing.”

When the first batch of COVID-19 vaccines arrived, she remembers, clinic duties for many nurses were suspended, sometimes for a full month at a time. “This was because during the national immunisation campaigns for COVID-19, we had to put a pause on routine services, including routine vaccinations and weighing.”

"We’ve had some shortages over the years, but never this widespread"

– Patrick Larbi-Debrah, public health officer

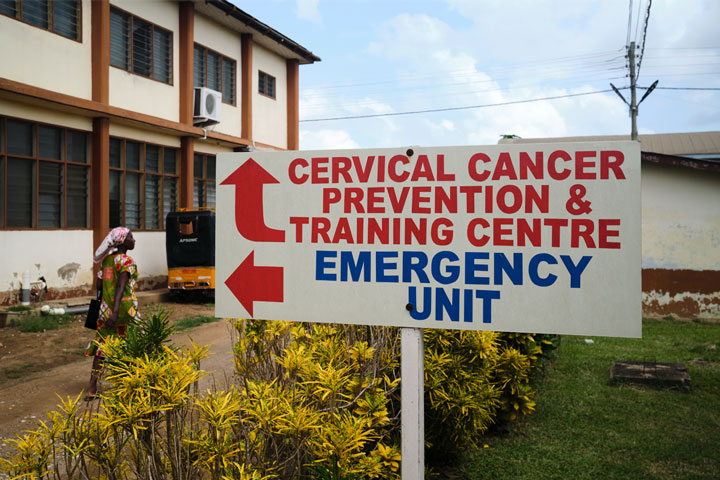

Across Ghana, the pandemic’s arrival threatened to erode the gains made over decades by the national immunisation programme.

In that, the west African nation wasn’t alone. The early pandemic’s lockdowns and transportation shutdownsaffected essential health systems around the world. By 2021, more than 68 countries had suspended vaccination services, putting an estimated 80 million children under the age of one at risk of contracting vaccine-preventable diseases.

Charged with oversight of immunisation in her municipal area, it’s Danquah’s job to close up the local immunity gap. To catch up on routine immunisation schedules, she and her team have organised numerous mop-up vaccination drives to ensure that all the children in their register were brought up to date.

“We usually do the mop-ups at the end of every quarter, but because of the huge backlogs, we were not sticking to our regular schedule,” says Joana Odei, a public health nurse who works with Danquah in Okaikwei North.

For weeks on end, on weekdays and weekends alike, she remembers, they combed through the communities, finding and vaccinating missed children.

“We were tired and stressed, and I remember my husband complaining about how often I was away from home.”

The hard work here and across Ghana seemed to pay off. According to data collected annually by WHO and UNICEF, by 2021, Ghana’s coverage with the third dose of diphtheria, pertussis and tetanus-containing vaccine (DTP3), which is conventionally used as a yardstick for immunisation coverage in general, had improved by one percentage point against 2019 levels, edging it back towards its pre-pandemic trajectory.

Those gains put Ghana in a relatively happy minority. Globally, DTP3 coverage fell five percentage points between 2019 and 2021.

But despite the sacrifices health workers like Danquah and Odei have made, and the successes achieved by their mop-up campaigns, new challenges are threatening their work

In late February 2023, the Daily Graphic, a national newspaper, reported a widespread shortage of vaccines used for the routine immunisation of babies from birth to 18 months, including those for polio, hepatitis B, measles and tuberculosis.

Have you read?

Patrick Larbi-Debrah, a public health officer with the Ghana Health Services (GHS), says that the Upper West Region of Ghana, for example, has had a shortage of the measles vaccine for the past nine months, which has been blamed for outbreaks that have affected some 120 people.

“Ever since Covid started, I’ve realised that there has been a shortage of all antigens, especially the oral poliovirus (OPV), measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR), and Rotavac vaccines. As of now we don’t have any of these antigens in my district, and even when we get them, they’re in small quantities. Mothers bring their babies to the clinic, and after counselling, we have to ask them to return later,” says Danquah.

“Most of them are busy trading trying to make ends meet, so you can imagine how angry they get when they make time to come to the clinic and we turn them away. They feel like we’re wasting their time and often don’t return.”

When this happens, she says, the list of defaulters grows, and the responsibility falls on her and her team to get things back on track.

“We need a steady supply of vaccines because we can’t afford outbreaks in these communities. These are mostly densely populated areas, so an outbreak could put many of our children in danger.”

Larbi-Debrah echoes Gloria’s fears saying, “This issue of vaccine shortage must be addressed permanently. We’ve had some shortages over the years, but never this widespread. Over the years we’ve built trust and acceptance with the caregivers in our communities who present their babies for immunisation, so if now they come and we repeatedly don’t have vaccines, it causes a break-down in trust.”

“We’ve received official communication from GHS that the shortage is because of the high inflation rates the country has been facing since last year and that the issue has been submitted before parliament, so we’re waiting for an update. The government is yet to provide funds to purchase the vaccines,” he says.

Daniel Kumi, who lives in Lapaz, has a 5-month-old baby girl who he says missed one of her vaccines in the last month. He’s worried about when she might receive it, as well as about the availability of vaccines she will need in future to keep her safe. He says, “I’m shocked that we’re facing this problem. I have a friend with a newborn who hasn’t yet received the BCG vaccine. What is going on? What should parents do?”

“I heard of an instance where a health worker was attacked by a frustrated mother who had been to the clinic numerous times but left with no vaccine for her baby,” says Larbi-Debrah.

“It’s not right but imagine this: You’ve vaccinated my child and it’s time for the next booster, so I come in and you tell me there’s no vaccine. I come again and again and there’s still no vaccine. It’s a real headache.”

Larbi-Debrah clarifies that the GHS has a catch-up policy which dictates that if a vaccine is missed, there is a window within which it can still be taken. “For instance,” he says, “BCG which protects children against tuberculosis is supposed to be given at birth, but our policy is such that when a mother visits you with a child under 1, the child can still be given the vaccine to protect them.”

Dr Patrick Kuma-Aboagye, the director general of the GHS, was quoted by VoA as saying that the shortages will be rectified by the end of March 2023.

“Once we receive the procurement of vaccines, the GHS will launch into action using our tried and tested methods to catch up on vaccination schedules,” says Larbi-Debrah. Among them, he goes on to say, are writing to community heads to inform them of impending vaccination drives so they can spread the information within their communities, having community health nurses conduct home visits to weed out defaulters, and providing immunization services at public events and festivals.

To protect its children, especially those in the inner cities and more densely populated communities, from exposure to life threatening but vaccine-preventable diseases, Ghana must, in the coming weeks find a lasting solution to its vaccine shortage issue.

* Gloria Danquah is not her real name