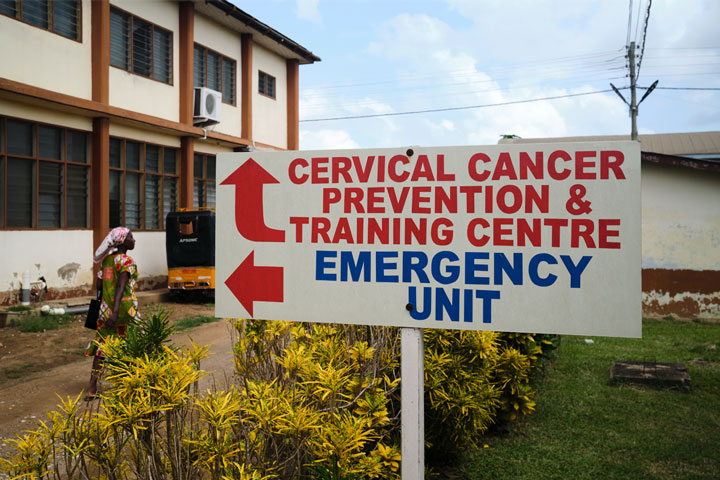

How one specialist health centre in Ghana is bulldozing barriers to cervical cancer screening

With over 18,671 women screened since 2017, the Cervical Cancer Prevention and Training Centre is equipping health workers and saving lives.

- 1 July 2025

- 9 min read

- by Nanama Boatemaa Acheampong

In Ghana, where only 3% of women have been screened for the disease, cervical cancer is the second-most common cause of cancer-related deaths among women, with an estimated 1,700 women lost to the illness each year. That’s because it’s often detected late, when treatment options are limited, expensive, or impossible.

Those mortality rates are set to change: Ghana’s Ministry of Health (MoH) has announced plans to introduce the cancer-blocking human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine into routine immunisation later this year, targeting adolescent girls nationwide with support from partners including UNICEF and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. The national roll-out will help fill the country’s prevention gap – a gap that for nearly a decade, one facility in Battor has been desperately trying to patch.

In the North Tongu District in the Volta Region of Ghana, a small, resolute team spearheaded by Dr Kofi Effah, an obstetrician-gynaecologist with over 23 years of experience, has been trying to get out ahead of cervical cancer.

Effah’s association with the Catholic Hospital, Battor began in 2002, but it wasn’t until May 2017, that he founded the Cervical Cancer Prevention and Training Centre (CCPTC) on the hospital’s premises. It wasn’t a grand vision backed by international funding or government policy. It was a practical response to a deadly problem.

“There were no real systems,” he says. “No training, no screening access, no HPV testing available at scale. So we built it ourselves.”

A centre built from scratch, and built to scale

At its core, CCPTC is a training facility. The model is straightforward: train nurses, midwives and other health workers to screen for and treat precancerous cervical lesions, then send them back to their communities to run local programmes. The centre provides technical training, equipment orientation, clinical practice and supervised outreach sessions.

Since 2017, 464 health workers have been trained by the centre, including 293 midwives, 126 nurses, 30 doctors, 15 physician assistants and 12 lab technicians.

“We train people with one mission in mind,” says Effah. “So they can leave here and start screening women the very next week.”

The impact is measurable: over 18,671 women screened at the CCPTC since inception. Of those, 171 women have been treated for precancerous lesions, using thermal ablation, cryotherapy and LEEP (loop electrosurgical excision procedure), depending on the type of cervical lesion and what’s locally available.

“It felt like I was always sitting on fire,” says Margaret Addai, a 64-year-old woman whose years of burning pain had been recurrently misdiagnosed. After connecting with Dr Effah’s team, in addition to her gynaecologic assessment and care, she was screened and diagnosed with a dangerous, persistent HPV infection. For five years, she returned annually to Battor for monitoring and treatment.

“I told them to take my womb. I didn't need it anymore. But the nurses told me to wait; that something good would come.”

That day came in 2024, when a nurse called her with news that she was finally HPV-free. “Mama, you are now free,” they said. “I cried that day.”

Her story is just one among thousands. “As a clinical nurse-specialist working in mental health and women’s wellness, I see the CCPTC experience as foundational to the multi-disciplinary model I now practise, where physical, psychological and preventative health go hand-in-hand,” says Gloria Sarkodie Addo, who now screens women at the Shai-Osukodu District Hospital in Dodowa.

There is no formal data yet on the number of late-stage referrals, but anecdotal evidence suggests that earlier screening is helping to catch more cases before they escalate.

The centre’s impact also reaches across borders. Zainab, a woman from Sierra Leone, discovered she had a precancerous lesion in 2018, after accompanying her mother to Ghana for cervical cancer treatment. She credits Battor with saving her reproductive health and has continued to return for follow-up care, even though she has since moved to Dubai.

When the system isn’t ready, build your own

At the time of CCPTC’s founding, Ghana’s HPV testing capacity was low, not least because there was also no clear policy enabling nurses to conduct advanced screening or treatment. Effah and his team had to sidestep all of that with a mix of science, advocacy and what he calls “constructive defiance”.

“When we started, only doctors were allowed to perform colposcopies,” he says, referring to an examination of the vagina and cervix using a magnifying instrument. “But that made no sense when nurses were doing the actual work in the communities.”

They reframed the technology as “enhanced visual inspection with acetic acid” to bypass regulatory bottlenecks. Now, specially trained nurses regularly perform screening using mobile colposcopes, a key innovation that allows real-time imaging and remote consultations

In 2021, the CCPTC collaborated with Lutech Industries Inc. in New York to develop the first mobile version of the Lutech digital colposcope, one of the world’s most advanced devices for cervical screening. The original Lutech colposcope was a stationary, clinic-bound device; with CCPTC’s technical input, it was re-engineered into a portable tool that could be carried into remote communities for outreach. The new, lightweight, camera-equipped tool is one of the mobile colposcopes used by the CCPTC now for many of screenings done at the centre and during outreach visits.

“We flipped the model,” says Nurse Annita Edinam Dugbazah, one of the lead nurses at the CCPTC. “Instead of asking doctors to do everything, we asked nurses to lead.”

Local problems, local solutions

A key part of Effah’s approach is local manufacturing. When imported vinegar (used for visual inspection with acetic acid) became too costly, the team partnered with Ghana Atomic Energy to manufacture it locally. They also locally produce cotton swabs and screening aids to reduce clinical costs.

Even the Centre’s screening in-house screening algorithms, detailing step-by-step clinical decisions, were developed three years before the World Health Organization (WHO) issued its own guidelines for cervical cancer screening in 2019.

“We didn’t want each nurse improvising on patients,” he explains. “So we created a decision tree, then turned it into an app that helps guide screening and treatment.”

The algorithms and apps pioneered at the centre have since been used to train dozens of cohorts and now serve as on-the-ground diagnostic tools in many facilities across the country.

Each trainee screens at least 15 women during their course, with screening costs included in the programme fee. Some participants pay out of pocket, while others are sponsored by their health centres. After completing training, many return to their regions to set up units or lead outreach sessions – CCPTC offers remote mentoring for health workers once they return to their facilities. The CCPTC maintains WhatsApp groups with its alumni, sharing updates, images, case discussions and new protocols.

“We don’t just hand them certificates,” says Effah. “We hand them a network.”

Have you read?

Much of CCPTC’s success rests on the robust training materials developed entirely in-house. In contrast to the short, three-day workshops typical of VIA (visual inspection with acetic acid), training, the centre designed a rigorous two-module programme. Module 1 introduces health workers to screening techniques, cervical pathology terminology, and how to set up functional screening units. Module 2 builds on this foundation with treatment skills, including cryotherapy and thermal ablation.

“We didn’t want nurses who could just perform a procedure – we wanted them to understand the language of global cervical cancer care,” says Dr Effah.

Reaching the unreachable

The centre has conducted screening outreach sessions in 51 communities, with five of those receiving multiple visits. These clinics bring services to remote and underserved populations.

“Most women don’t know what a cervix looks like, so we show them,” says Annita. “When they see the images and understand what cancer actually looks like, it removes the fear.”

The team uses HPV Atlas boards: visual flipbooks showing images of infected cervixes, genital warts and normal reproductive anatomy. Through these sessions, over 250,000 women have received community education.

One experience stuck with Annita: “There was one woman who came in with this terrible smell. She was too embarrassed to even speak. After the screening, she brought her sisters from Koforidua to get screened too. That kind of trust, you can’t buy it.”

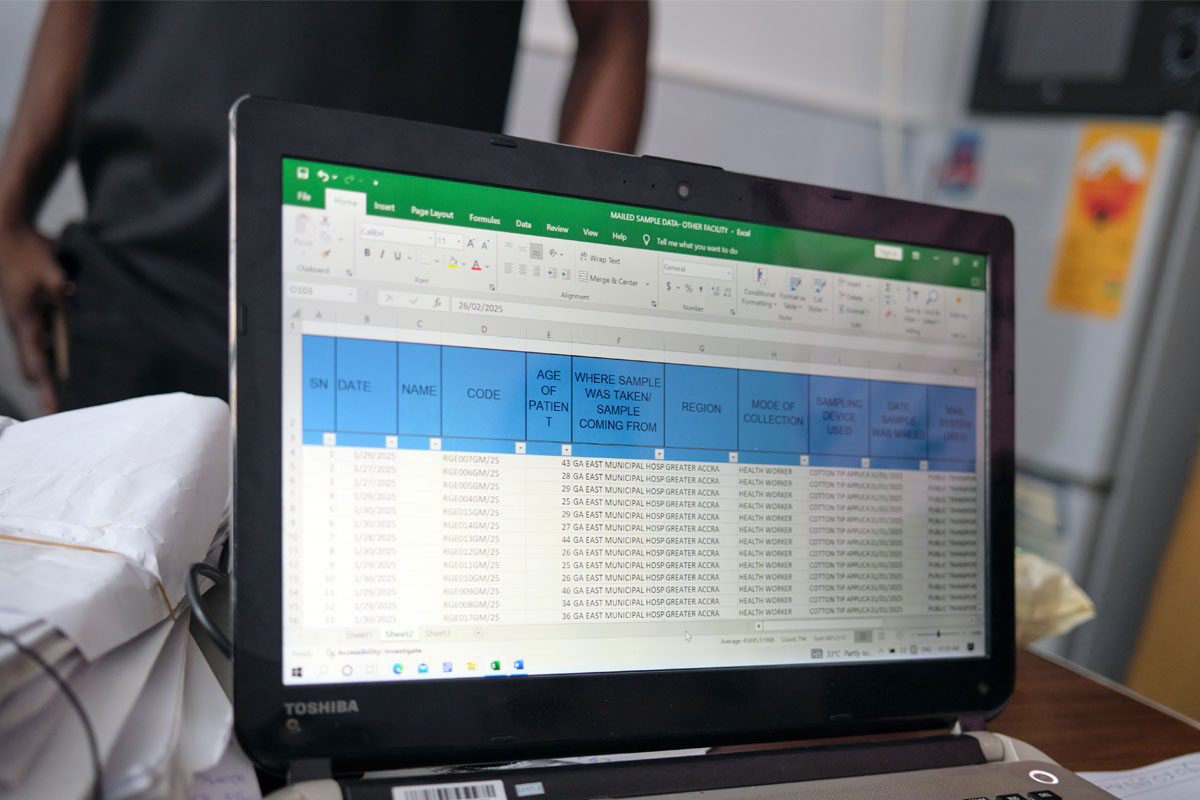

Data, diagnostics and a lab with purpose

The centre’s lab processes thousands of HPV samples annually, not just from Battor, but from health facilities across the country that lack testing capacity. They’ve compared multiple testing platforms, published over a dozen peer-reviewed papers, and are now a reference point for HPV diagnostics in Ghana.

Over the years, the team has worked with a range of diagnostic platforms, starting with careHPV (a WHO-prequalified, portable system designed for low-resource settings), followed by GeneXpert (a rapid, cartridge-based system), and AmpFire (a fast, high-throughput PCR test). Most recently, they adopted the MA-6000, a PCR-based platform offering full genotyping of HPV. The CCPTC team chose the MA-6000 because it provided local technical support, greater affordability, and dependable performance in their setting.

“We didn’t just want accuracy, we needed something we could maintain here, long-term,” says Dr Effah.

But testing alone isn’t enough if patients don’t return for results or follow-up care.

To tackle this, CCPTC introduced concurrent HPV DNA testing and a visual inspection method (VIA or mobile colposcopy), especially in low-resource settings. This integrated approach significantly reduces the risk of women being lost to follow-up, a common problem in cervical cancer prevention programmes globally, especially in resource-limited settings.

“We saw that women often couldn’t afford to come back multiple times,” says Effah. “So we brought everything together. Now, they can be screened, visualised and diagnosed in one sitting.”

In many cases, if a precancerous lesion is found, treatment such as thermal ablation can be done on the spot. This same-day model has become a benchmark for effective care delivery and a key part of CCPTC’s push for decentralised, community-accessible services.

Retention and the realities of scale

Not every trainee continues screening after six months. Barriers include lack of support from facility leadership, equipment shortages and shifting roles. While exact retention data is still being compiled, many remain active through informal networks or self-organised clinics.

“Some of them do screenings on weekends. Some partner with churches. The system hasn’t caught up yet, but the motivation is there,” Effah says.

What has been established is reach: thanks to a Rotary grant that funded 50 thermal coagulators, all 16 administrative regions in Ghana now have at least one site capable of treating pre-cancer.

Still, Effah wants more: “We have 261 districts in Ghana. We’ve covered about 60%. The next 40%, we need funding to reach.”

Beyond the clinic

The CCPTC has become more than a training centre. It’s a research hub, a community anchor, and a symbol of what’s possible when a system is built for people, not paperwork.

“It wasn’t meant to be a centre,” he says. “It was meant to be a solution.”

The true legacy of his work may not lie in accolades or recognition, but in the passion and fierce legacy it unlocks in others. Nurses, midwives and health workers across Ghana have made his vision their own, and are carrying it into communities, turning their training into transformation. Among them is Miriam Bonah, National Best Nurse 2024, who, between 2023 and 2024, has screened over 800 women in the Northern Region.

“I began to see that, look, this thing is spreading,” she says. “If we don’t do something about this, we are losing women. We are losing women who are productive.”

Bonah’s voice, like that of so many CCPTC alumni, captures the heart of what Effah has built – a movement powered by determined leadership, practical skills and a deep, infectious sense of purpose.